In the British Museum there is a splendid piece o f horn o f this , species which was dredged

from the Dogger Bank in the North Sea.

D a w k in s ’s Deer (Cervus Dawkinsi).— A deer with a palmated antler, whose type seems

to approach that o f the elk family.

S a v i n ’ s D e e r (Cervus Savini%^h. large deer resembling the red deer.

C e r vu s V e r t ic o r n i s .— Another large deer whose horns resemble those o f the red deer,

except that in adult animals the horns become more palmated and thicker and are apt to

throw off tines at almost any point o f the anterior or posterior margin o f the beam.

C e r v u s P o l ig n a c u s .— Another large deer with a long brow point, whose beam spreads

into palmation, like that o f the fallow deer, about io£ inches from the base.

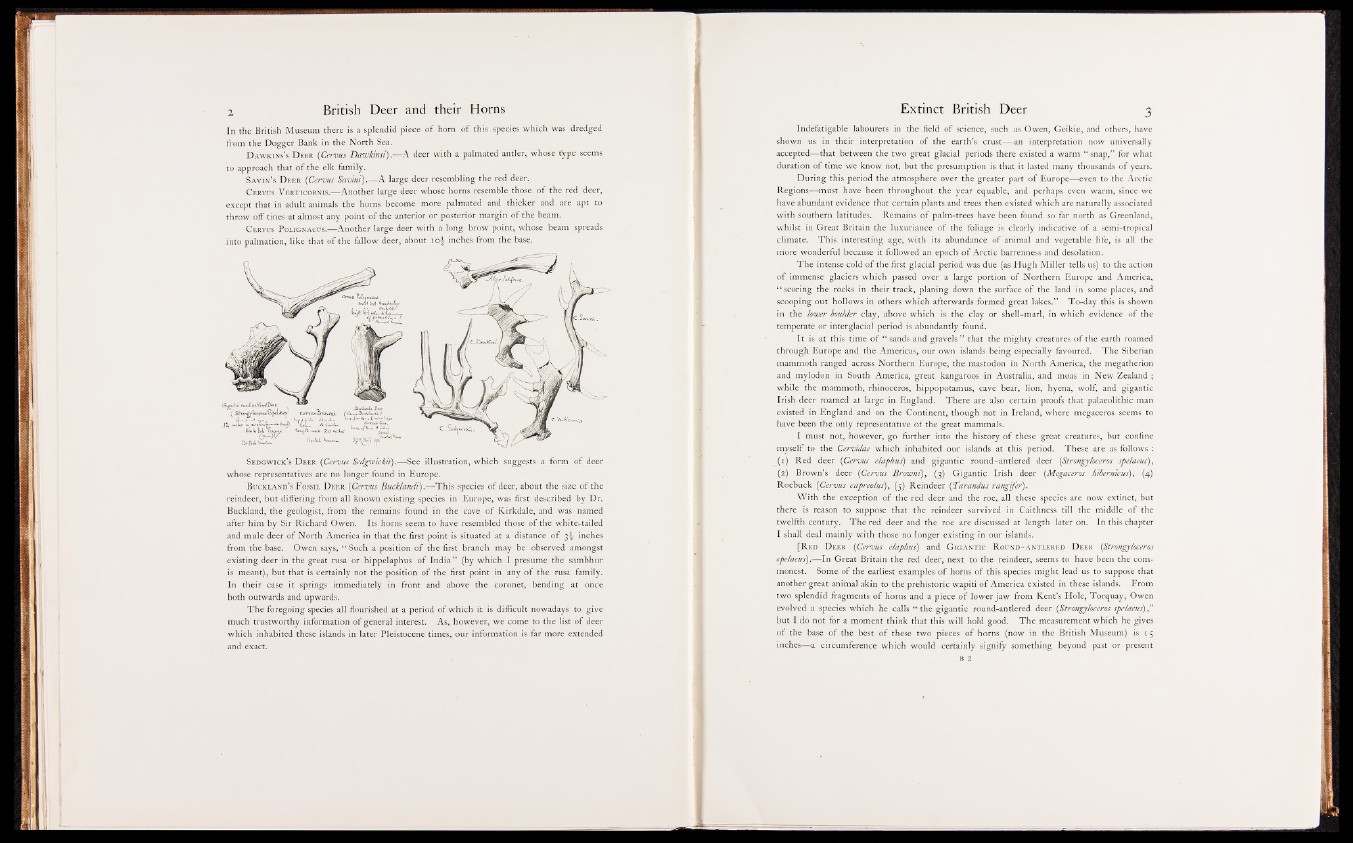

S e d g w ic k ’s D e e r (Cervus Sedgwickii).— See illustration, which suggests a form o f deer

whose representatives are no longer found in Europe.

B u c k l a n d ’s F o s sil D e e r (Cervus Bucklandi).— This species o f deer, about the size o f the

reindeer, but differing from all known existing species in Europe, was first described by Dr.

Buckland, the geologist, from the remains found in the cave o f Kirkdale, and was named

after him by Sir Richard Owen. Its horns seem to have resembled those o f the white-tailed

and mule deer o f N orth America in that the first point is situated at a distance o f 3-^ inches

from the base. Owen says, “ Such a position o f the first branch may be observed amongst

existing deer in the great rusa or hippelaphus o f India ” (by which I presume the sambhur

is meant), but that is certainly not the position o f the first point in any o f the rusa family.

In their case it springs immediately in front and above the coronet, bending at once

both outwards and upwards.

T h e foregoing species all flourished at a period o f which it is difficult nowadays to give

much trustworthy information o f general interest. As, however, we come to the list o f deer

which inhabited these islands in later Pleistocene times, our information is far more extended

and exact.

Indefatigable labourers in the field o f science, such as Owen, Geikie, and others, have

shown us in their interpretation o f the earth’s crust— an interpretation now universally

accepted— that between the two great glacial periods there existed a warm “ snap,” for what

duration o f time we know not, but the presumption is that it lasted many thousands o f years.

During this period the atmosphere over the greater part o f Europe— even to the Arctic

Regions— must have been throughout the year equable, and perhaps even warm, since we

have abundant evidence that certain plants and trees then existed which are naturally associated

with southern latitudes. Remains o f palm-trees have been found so far north as Greenland,

whilst in Great Britain the luxuriance o f the foliage is clearly indicative o f a semi-tropical

climate. This interesting age, with its abundance o f animal and vegetable life, is all the

more wonderful because it followed an epoch o f A rctic barrenness and desolation.

The intense cold o f the first glacial period was due (as Hugh Miller tells us) to the action

o f immense glaciers which passed over a large portion o f Northern Europe and America,

“ scoring the rocks in their track, planing down the surface o f the land in some places, and

scooping out hollows in others which afterwards formed great lakes.” To-day this is shown

in the lower boulder clay, above which is the clay or shell-marl, in which evidence o f the

temperate or interglacial period is abundantly found.

It is at this time o f “ sands and gravels ” that the mighty creatures o f the earth roamed

through Europe and the Americas, our own islands being especially favoured. The Siberian

mammoth ranged across Northern Europe, the mastodon in North America, the megatherion

and mylodon in South America, great kangaroos in Australia, and moas in New Zealand ;

while the mammoth, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, cave bear, lion, hyena, wolf, and gigantic

Irish deer roamed at large in England. There are also certain proofs that palaeolithic man

existed in England and on the Continent, though not in Ireland, where megaceros seems to

have been the only representative o f the great mammals.

I must not, however, go further into the history o f these great creatures, but confine

myself to the Cervidae which inhabited our islands at this period. These are as follows :

(1) Red deer (Cervus elaphus) and gigantic round-antlered deer (Strongyloceros spelaeus),

(2) Brown’s deer (Cervus Browni) M m Gigantic Irish deer (Megaceros lubernicus), (4)

Roebuck (Cervus capreolus), (5) Reindeer (Tarandus rangifer).

With the exception o f the red deer and the roe, all these species are now extinct, but

there is reason to suppose that the reindeer survived in Caithness till the middle o f the

twelfth century. The red deer and the roe are discussed at length later on. In this chapter

I shall deal mainly with those no longer existing in our islands.

[ R e d D e e r (Cervus elaphus') and G ig a n t i c R o u n d - a n t l e r e d D e e r (Strongyloceros

spelaeus).— In Great Britain the red deer, next to the reindeer, seems to have been the commonest.

Some o f the earliest examples o f horns o f this species might lead us to suppose that

another great animal akin to the prehistoric wapiti o f America existed in these islands. From

two splendid fragments o f horns and a piece o f lower jaw from Kent’s Hole, Torquay, Owen

evolved a species which he calls “ the gigantic round-antlered deer (Strongyloceros spelaeus)”

but I do not for a moment think that this will hold good. T h e measurement which he gives

o f the base o f the best o f these two pieces o f horns (now in the British Museum) is 15

inches— a circumference which would certainly signify something beyond past or present