lying within a few yards o f the g o t where I fired at him. Accompanying the letter were

Old Queer Head’s skull and horns, which present a curious malformation. One pedicle has

been jammed down backwards and inwards, so that the two horns follow one another on the

head, like the hands o f a vulgar little boy in the act o f “ cocking a snook.” It was entirely

emblematic o f his career.

This little yarn is intended to show that a roe is not always an easy creature to circumvent

even when he does inhabit a limited area ; and in the many enjoyable^ days roe-stalking

that have fallen to my lot I can recall plenty o f instances when the roe has afforded every

bit as good sport as the stag. One day at Eskadale Hugh Ross and I had a somewhat curious

experience. We had toiled all day, from daybreak till dusk, and were in the evening about

to turn uphill to the cottage, when there, right in the middle o f the public highroad, the

last place one would o f course have expected to see him, stood a buck. Just as I fired he

moved, and the bullet merely cut the skin under the brisket. It gave him such a fright,

however, that instead o f turning back into the wood, he sprang forward and cleared a high

wall which led downhill to open fields skirting the Beauly. After running for some time I

expected every second he would stand and offer me another chance ; but no, on he ran till he

reached the swollen river, into which he plunged without a moment’s hesitation. I was not

so very far behind, and as he reached the middle o f the river, fired at his head— result, a miss

just over the top. Then another shot, and the head fell to one side and drifted down the

stream. Though our buck was now dead, the fun had only just begun, for not 800 yards

below were the rushing rapids, where no one but a fool would go even in the stout coble

lying upside down on the shingle close by. Never on this earth was there such a boat to

move as that, and we saw the buck come drifting by as Ross and myself toiled and sweated

to move the wretched thing from the weeds that had grown around it. A t last it was

launched and the roe recovered from the river just as we were entering the Ailean Aigas

rapids.

R O E H E A D S

A good stag’s head, even nowadays, is not by any means rare ; but a first-class roebuck’s

head is, and I believe always has been, quite a rarity.

In a season’s shooting one sees many fine examples o f the former, although they may

not always measure well, but it is quite an exceptional year when more than three or four

first-class roebucks’ heads pass into the hands o f the stuffers.

A t the beginning o f the last chapter I mentioned how very unusual it was to find horns

of the roe o f Pleistocene times which were in any degree better than those o f to-day, and I

give a photograph o f the only two which have come under my notice. Only since the year

1892 has there been any marked deterioration in the horns o f Scottish roe, and this only

applies to thé greater part o f the country north o f Inverness, for in. other parts there is

no perceptible difference.1 With regard to roe heads the usual talk about deterioration does

1 In 1895 Mr. Lucas Tooth kindly gave me a day at Beaufort. On the open roe ground of Kiltarlity, working hard all day,

from daylight till dark, I Only saw two very poor bucks with wretched heads. In 1890 I once saw no less than seven good

bucks in an evening on this same ground.

not apply, for in the collections o f the late Seaforth and Roualeyn Gordon-Cumming (the

great collectors o f roe heads in their day) there were no examples better than recently-killed

heads now in collections which are here illustrated.

The best roe heads now found are grown by animals inhabiting districts within 15

miles o f Perth, Beauly, and Forres. I give an illustration o f three very fine typical heads

in my collection from these areas, showing how, even at such short distances apart, the

difference o f shape and quality is entirely due to environment (p. 206).

Sometimes a good head is obtained in the woods near Stirling, in the south of

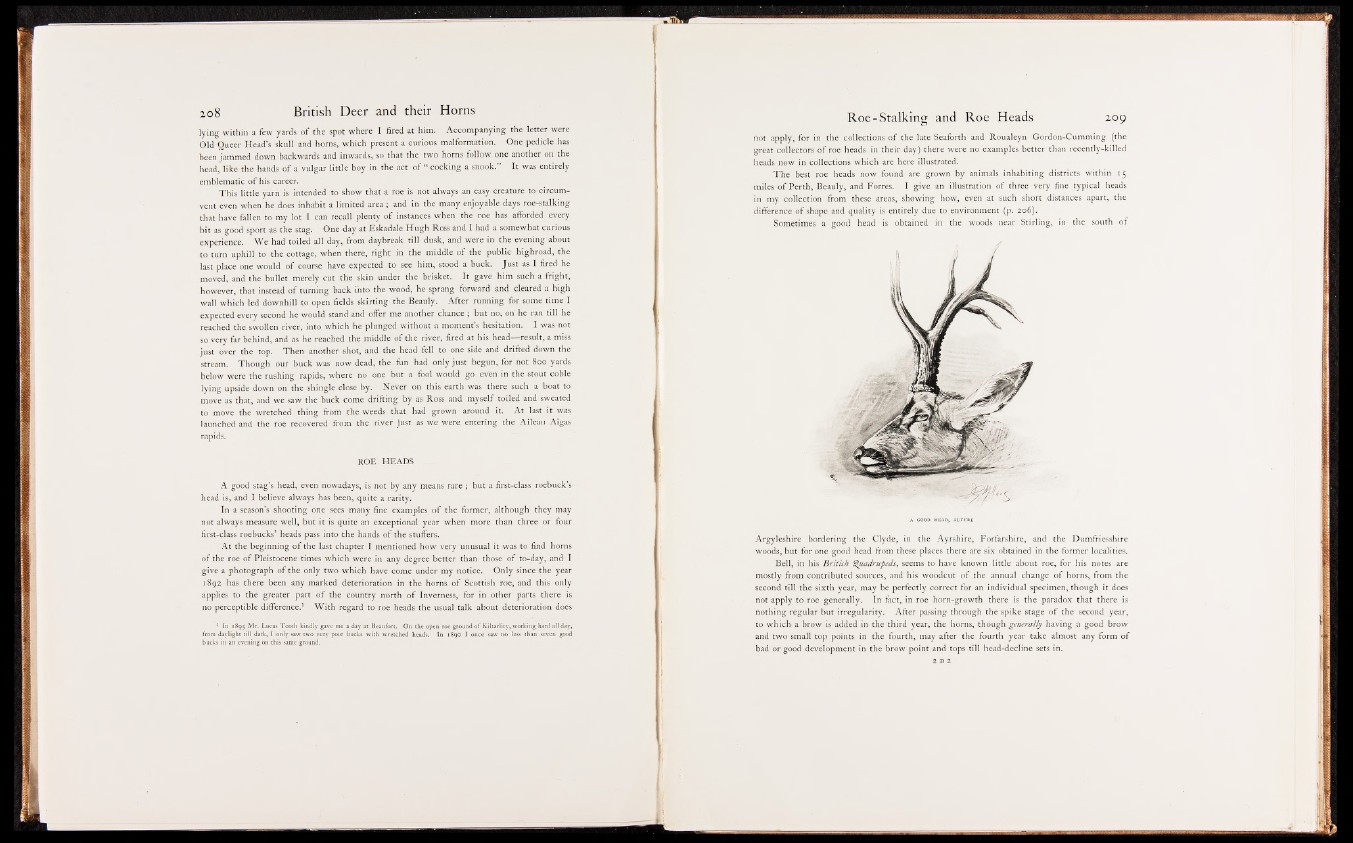

A GOOD HEAD, ALTYRE

Argyleshire bordering the Clyde, in the Ayrshire, Forfarshire, and the Dumfriesshire

woods, but for one good head from these places there are six obtained in the former localities.

Bell, in his British Quadrupeds, seems to have known little about roe, for his notes are

mostly from contributed sources, and his woodcut o f the annual change o f horns, from the

second till the sixth year, may be perfectly correct for an individual specimen, though it does

not apply, to roe generally. In fact, in roe horn-growth there is the paradox that there is

nothing regular but irregularity. After passing through the spike stage o f the second year,

to which a brow is added in the third year, the horns, though generally having a good brow

and two small top points in the fourth, may after the fourth year take almost any form of

bad or good development in the brow point and tops till head-decline sets in.

2 d 2