From the large number o f heads that have been dug up in Ireland alone, we conclude that

the species must have been very abundant in later Pleistocene and prehistor|ptimes, This

is easily'accounted for in the case pfi Ireland from the feet j | ) t (with the exception o f

wolves) it can have had scarcely any natural enemies amongst the larger carnivora, and in

England, Scotland, and Western Europe it is doubtful i f creatures like the great cave tiger

and the cave bear could be considered formidable enemies when the question o f speed is

taken into consideration.

• As before remarked, the gigantic Irish deer lived in the warm interglacial period,

and the extraordinary annual growth o f antler attests to the luxuriance and abundance of

pasturage in those times. In the British Isles the deer seem to have been most numerous

in Ireland, where remains are found, below all the bogs in the lacustrine shell-marl. In

County Limerick the greatest number o f heads has been dug up, notably in the extinct

lake o f Loch Gur, where literally hundreds o f them have been unearthed. In 1875

Mr. R. J. Moss made excavations in the bog o f Ballybethag, nine miles south-east o f Dublin,

and was so successful that Mr. W . Williams, the Dublin naturalist, was induced to make

similar researches in the same locality during the summers o f 1876 and 1877. He too was

equally fortunate, twenty-six heads and three complete skeletons being the result o f his

digging. From that date to the present time no one has been so successful as Mr. Williams

in recovering the heads and horns o f this great deer, and I think it is not too much to say

that the vast majority o f the specimens now in British collections owe their presence there to

this indefatigable searcher. Below the great bog in the vicinity o f Tullamore is another

productive district, as is also the margin o f Loch Derg (County Galway) and Killowen

(County Wexford).

T h e first tolerably perfect skeleton o f the megaceros was found in the Isle o f Man,

and was presented by the Duke o f Atholl to the Edinburgh Museum.

In England the remains o f this great deer are rare. Owen tells us that the first skull

and antlers were dug out o f the peat moss at Cowthorpe in Yorkshire. There are also

evidences o f its having existed at Walton in-Essex and Hillgay in Norfolk and in the peat

bogs o f Lancashire ; whilst complete heads and antlers have recently been found in the

south-west o f Scotland. Lartet, the French naturalist, observes that the habitat o f this

animal seems to have been much more contracted than that o f the mammoth, and he tells

us that its remains are found in France westward only to the foot o f the Pyrenees. In the

valley o f the Oise, M. L ’Abbe Ed. Lambert has found it associated with Elaphus primigenius,

Rhinoceros tichorhinus, hippopotamus, reindeer, and musk ox.

In Germany the remains have been found as far east as Silesia, and the caves o f the

Altai denote the extreme eastern limit o f the ascertained range o f this animal.

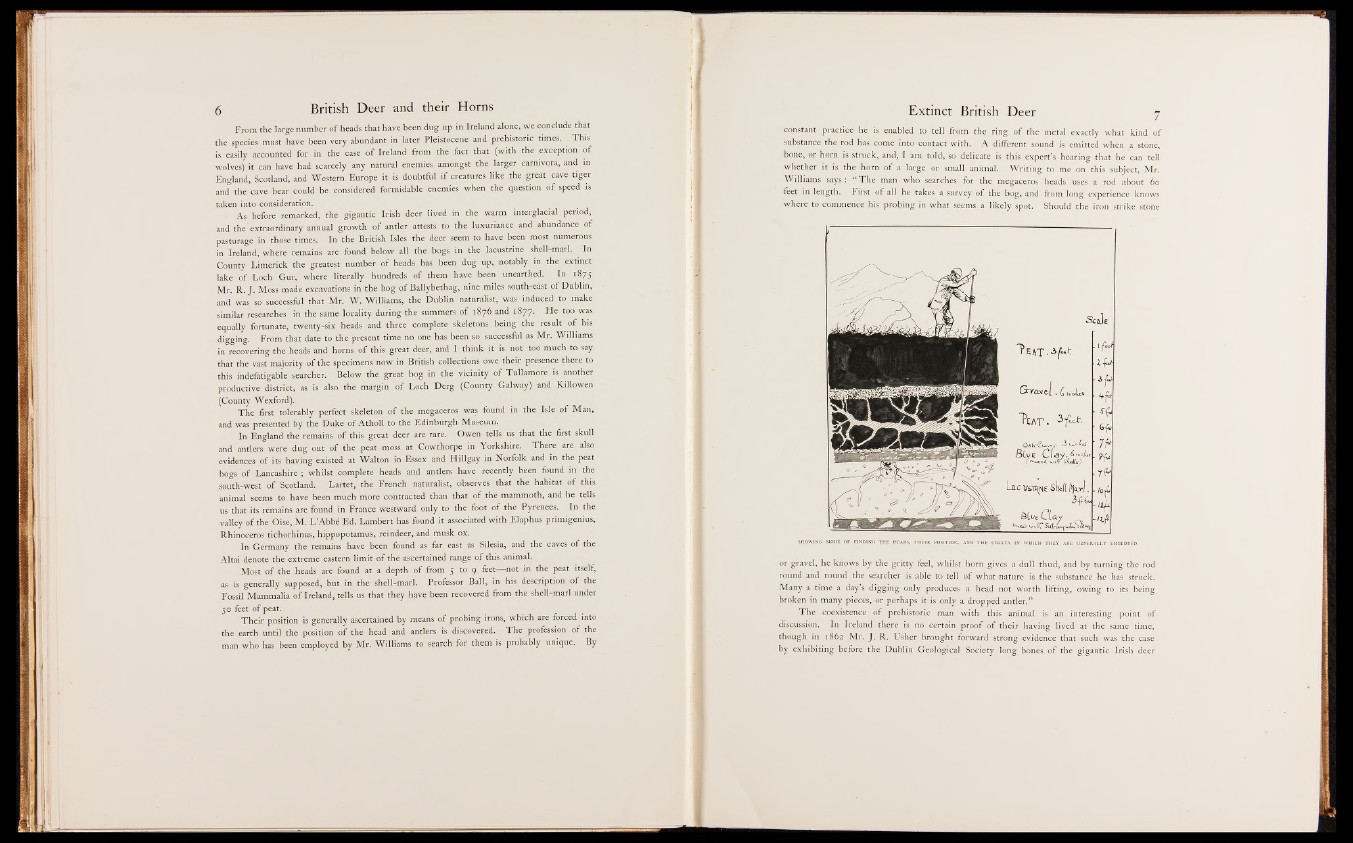

Most o f the heads are found at a depth o f from 5 to 9 feet— not in the peat itself,

as is generally supposed, but in the shell-marl. Professor Ball, in his description o f the

Fossil Mammalia o f Ireland, tells us that they have been recovered from the shell-marl under

50 feet o f peat.

Their position is generally ascertained by means o f probing irons, which are forced into

the earth until the position o f the head and antlers is discovered. T h e profession o f the

man who has been employed by Mr. Williams to search for them is probably unique. By

constant practice he is enabled to tell from the ring o f the metal exactly what kind o f

substance the rod has come into contact with. A different sound is emitted when a stone,

bone, or horn is struck, and, I am told, so delicate is this expert’s hearing that he can tell

whether it is the horn o f a large or small animal. Writing to me on this subject, Mr.

Williams says: “ T h e man who searches for the megaceros heads uses a rod about 60

feet in length. First o f all he takes a survey o f the bog, and from long experience knows

where to commence his probing in what seems a likely spot. Should the iron strike stone

or gravel, he knows by the gritty feel, whilst horn gives a dull thud, and by turning the rod

round and round the searcher is able to tell o f what nature is the substance he has struck.

Many a time a day’s digging only produces a head not worth lifting, owing to its being

broken in many pieces, or perhaps it is only a dropped antler.”

T h e coexistence o f prehistoric man with this animal is an interesting point of

discussion. In Ireland there is no certain proof o f their having lived at the same time,

though in 1862 Mr. J. R. Usher brought forward strong evidence that such was the case

by exhibiting before the Dublin Geological Society long bones o f the gigantic Irish deer