Eskadale woods, lying sometimes in the corn-fields during the day, but swimming back to

his island home at night. During a visit to Ailean Aigas early in August 1891, I found

the fern banks on the top o f the island literally covered with his beds, whilst the steep

descent on either side to the river was worked into regular paths by his hoofs. O f his

further history I shall have something to say later on.

The weird, wild, yawning roar o f the stag is certainly one o f the grandest sounds in

Nature, and when heard for the first time makes an impression not easily forgotten ; but

to compare it, as so many do, with the roar o f a lion is simply absurd.1 The voice o f the

lion is immeasurably louder, grander, and farther-reaching, and I think it is due only to

the natural advantages the stag enjoys in its usual environment o f echoing hills and dales

that this comparison has ever been made. I had a fine opportunity o f testing the actual

power o f the lion’s roar in the autumn o f 1894, and again in 1895, while staying with my

people in their Highland home on the hill o f Kinnoul, above the fair city o f Perth— ■ $. city

which, I may say, lies in a hole surrounded by hills on three sides. T o Perth one day

came Bostock’s menagerie, and with it two splendid lions, who, at intervals during the day,

did their best to alarm the inhabitants and inform them the show had -begun, by an

exhibition o f their vocal powers in full blast. Now a lion’s “ best ” in the roaring line is

quite a different thing from the moan o f subdued roar one generally hears in the wilds of

A frica; so here was a chance for finding out how far their voices could be heard, and on

this quest I presently set out. Mounting to the top o f Kinnoul H ill— a distance in a

bee-line o f two mile#^!•'■ found the sound there loud and strong; then following the line

o f the hills which run parallel to the T a y down the Carse 0’ Gowrie, a walk o f two miles

farther brought me to Kinfauns, where the sounds were still loud, and there could be

no question as to the animals that were, emitting them. Another two miles took me to

Glen Carse, where, as I stood on the station platform, I could distinctly hear the now

subdued sounds still coming from Perth. Glen Carse is in the flat, and six miles from the

South Inch o f Perth, where the caravans stood; one may therefore fairly assume that at a

higher elevation still farther away the roaring could be distinctly heard. In 1895, when

the menagerie revisited Perth, I again heard the lions roar at a distance o f six miles. Now

I maintain that on a still day no stag in existence could make itself heard so far away,1 2

and I doubt very much whether, amidst the hum and hubbub o f the busy city o f Perth,

with its tuneful steam whistles and other factory appliances constantly “ on the go,” its

roar would reach much (if any) farther than from the rendezvous o f the menagerie to the

top o f Kinnoul Hill.

March and April are the fatal months for deer, for they do not, as a rule, succumb

during great privations, but afterwards. Extremes o f climate affect deer very much.. A

continuously wet season upsets their stomachs, and a very dry one, besides being bad for

calving, drives them to the mountain-tops, where, though they escape the flies* they find

only poor and wiry grass, the consumption o f which generates inferior heads. This was

well seen in the wonderful season o f 1893. In the favoured region o f the Northern forests

1 It is not perhaps generally known that a stag when suddenly frightened-will bark loudly, and will gallop away, continuing

to bark at intervals. The noise emitted is much louder than that made by the hind.

2 It is only on very still autumn days that I can hear the stags roaring in Warnham, a distance from my house of two miles.

the deer flourished as they had never done before both in horn and body, while at Black

Mount and other forests farther south, where hardly any rain fell during the summer, the

heads were o f the poorest description, though in other respects the condition o f the animals

was fairly good.

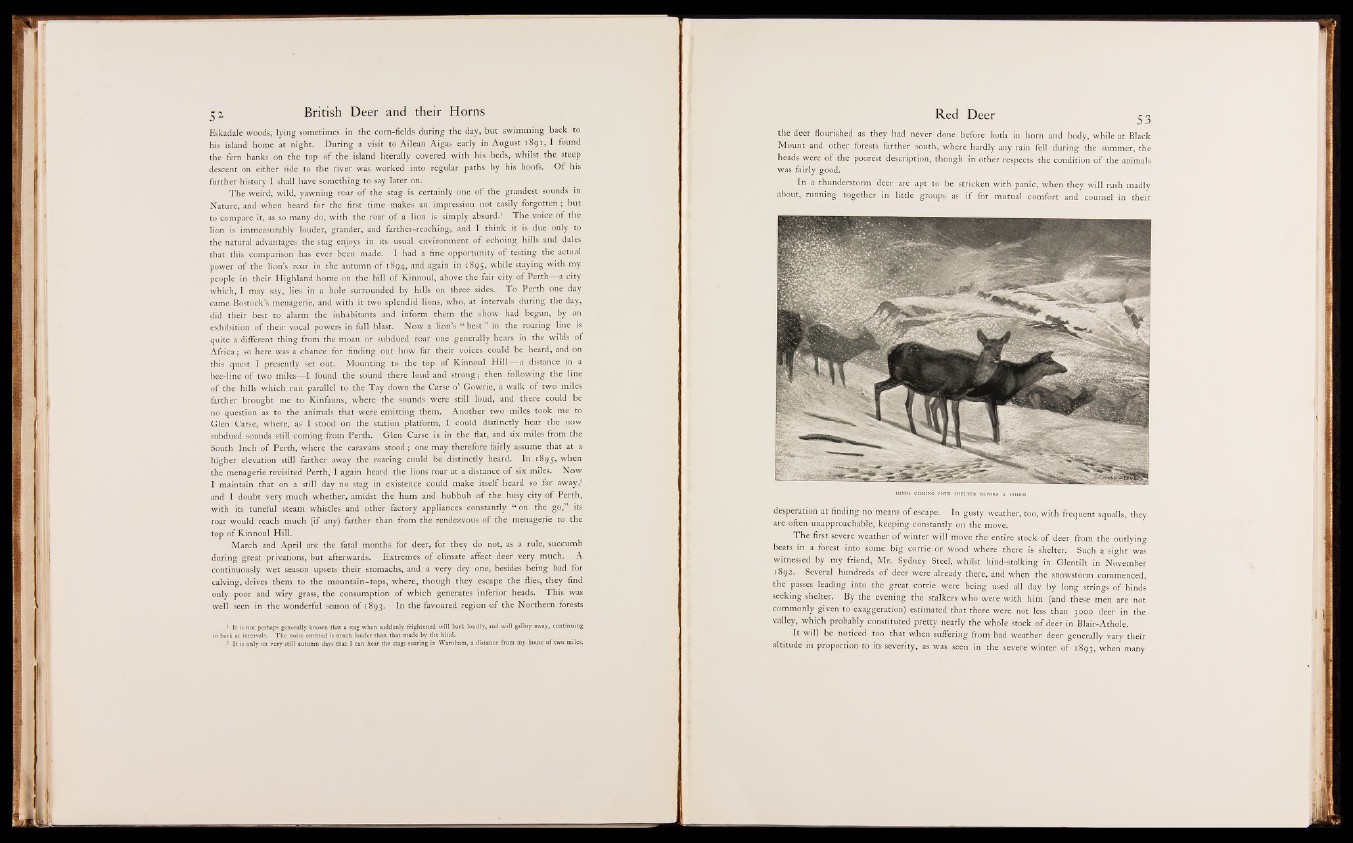

In a thunderstorm deer are apt to be stricken with panic, when they will rush madly

about, running together in little groups as i f for mutual comfort and counsel in their

desperation at finding no means o f escape. Insgusly* weather,*®, w ith frequent SqjialS they

are often unapproachable, keeping ‘constantly on the move.

The first severe weather o f winter will move tile entire stock o f deer from the outlying

a g g l i t . intp some big come or wood where there is shelter. Such a sight was

witnessed by my friend, Mr. Sydney Steel, whilst hind-stalking in G le n t i f in November

1892. Several hundreds o f deer were already there, and when the snowstorm commence||tl

the passes leading into the great jCorrie were being used all day by long stringS^f-hinds

seeking shelter. By the evening tlie stalkers who were with him (and these men ate ni l

commonly given to exaggeration) estimated that there were M p Jhaii 3000 deer in the

valley, which probably constituted pretty nearly the whole stock o f deer in Blair-Athole.

It will be noticed too that when sufferingyfrom bad weather deer generally vary their

altitude in proportion to its severity, as was seen in the severe winter o f 1893, when many