Two or three o f the does, even the old ones, for they do. not ever seem to get blasé, agj| a

last year’s calf or two start off and chase each other sometimes for over a mile, perhaps even

right round the park. After every “ shd|| burst ’’ they stop, buck, and skip about in the most

ridiculous fashion, and again shaking their heafsj.pretend to butt at each other like their

homed relations,’ This brings them to a standstill, but only for a moment, when off they

go again, chasing one another as hard as they can pelt. So the high jinks §ik on till they

perhaps have made the circuit o f the park and worked back to their original position.

These are the high old times o f yq fth before nature reminds the prospective mothers- .Of the

stern realities o f life, and that their figures are not quite what they were a month or two

previously. A fallow doe, though doubtless as .devoted to her ca lf as a red hind, seldom

displays the motherly concern o f the latter when danger threatens. She i? much more

cunning, and will gallop right away from it and joB|the herd sooner without hanging round

and HSlensibly showing her distress, as the other Susies o f deer will often d B I think too

that fallow calves get on their legs quicker and can take care o f themselves sooner than the

r j lp e e r calves. The fallow doe generally drbps her calf in the first week in June, and in good

seasons a little earlier; she rarely has more than one, though sometimes; t h f f i are two.

Occasionally we hear o f calves appearing, as in the case of red deer, in any o f the succeeding

months, evefi as late as November, but this isw 'a u r s d veyy rare.

Excepting in a park which is public and the -deer' have people amongst-them all day

long, fallow deer usually become shy during the summer months, always evincing distrust

and taking immediate alarm i f anything like real danger threateiH Food i§ abundant, f j

man can be avoided, and it is only on the approach o f the rutting ;seaj|>n that they once

again become somewhat tame and ind ifferent^ surroundings.

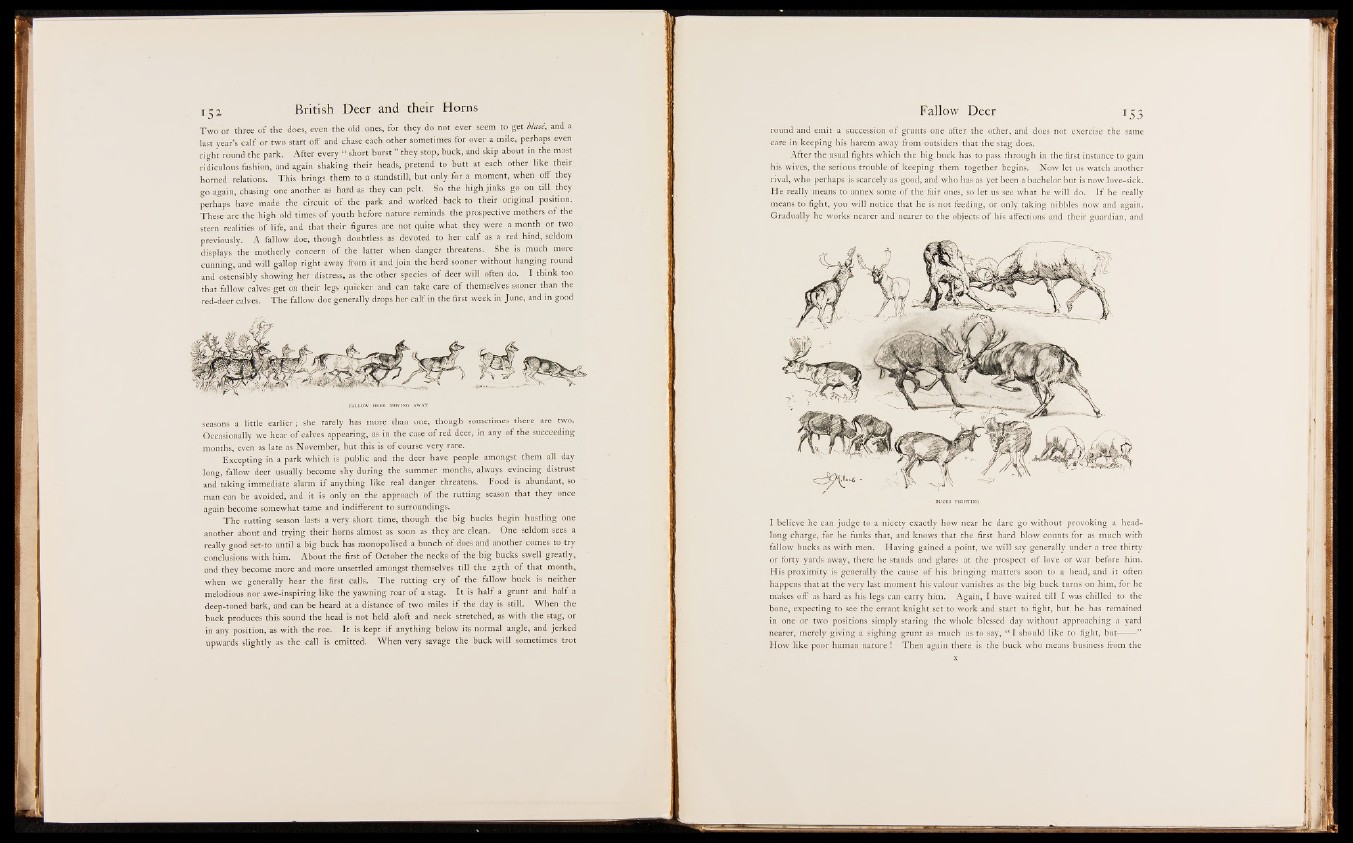

The rutting season lasts a very short time, though the big bucks begin bustling ope

another about and trying their horns almost as soon as they are clean. One seldom sees a

really good set-to until a big buck has monopolised a bunch o f does and another comes to try

conclusions with him. About the first o f October the necks o f the big bucks swell greatly,

and they become more and more unsettled amongst themselves till the 25th o f that month,

when we generally hear the first calls. The rutting cry o f the fallow buck is neither

melodious nor awe-inspiring like the yawning roar o f a stag. It is half a grunt and half a

deep-toned bark, and can be heard at a distanyd o f two miles i f the day is still. When the

buck produces this sound the head is not held aloft and neck stretched, as with the stag, or

in any position, as with the roe. It is kept i f anything below its normal angle, and jerked

upwards slightly as the call is emitted. When very savage the buck will sometimes trot

round and emit a succession o f grunts one after the other, and does not exercise the same

care in keeping his harem away from outsiders that the stag does.

After the usual fights which the big buck has to pass through in the first instance to gain

his wives, the serious trouble o f keeping them together begins. Now let us watch another

rival, who perhaps is scarcely as good, and who has as yet been a bachelor but is now love-sick.

He really means to annex some o f the fair ones, so let us see what he will do. I f he really

means to fight, you will notice that he is not feeding, or only taking nibbles now and again.

Gradually he works nearer and nearer to the objects o f his affections and their guardian, and

I believe he can judge to a nicety exactly how near he dare go without provoking a headlong

charge, for he funks that, and knows that the first hard blow counts for as much with

fallow bucks as with men. Having gained a point, we will say generally under a tree thirty

or forty yards away, there he stands and glares at the prospect o f love or war before him.

His proximity is generally the cause o f his bringing matters soon to a head, and it often

happens that at the very last moment his valour vanishes as the big buck turns on him, for he

makes off as hard as his legs can carry him. Again* T have waited till I was chilled to the

bone, expecting to see the errant knight set to work and start to fight, but he has remained

in one or two positions simply staring the whole blessed day without approaching a yard

nearer, merely giving a sighing grunt as much as to say, “ I should like to fight, but------ ”

How like poor human nature ! Then again there is the buck who means business from the