Then, how does a hare swim? a rabbit, a squirrel, or a stoat^. One hot day in

August 1894, while lazily smoking my pipe in the beautiful Stobhall woods that overlook

the famous stretch o f the Tay, Mr. James Pullar had kindly given me a day on his water,

and that “ pipe o f peace” (or piece o f pipe, for it was but a remnant o f its former self) seemed

specially sweet after lunch, for I had caught a splendid clean-run fish o f 36 lbs. and two grilse

that very morning in Eels Brig stream. And now a hare, running down the opposite bank

o f the river on Tay mount property, attracted my attention, and I watched him with keen

interest, for, continuing his easy canter to the edge o f the river, he plunged in without a

moment’s halt and made straight for the middle o f the stream. I had never before seen a

hare voluntarily take to a big sheet o f water, and in this case the stream was both heavy and

rapid. Until half-way across he was apparently going strong and well, but on encountering

the full force o f the current he seemed to lose heart, and suddenly turned back. Landing

again about 30 yards below the starting-point, he cantered along the stones nearly 50 yards

farther up the river and again launched himself in the rough water. This time he was borne

down rapidly, although straining every nerve to avoid this, and again (when he could most

firste, and the thyrde upon the backe of the second, and consequently al the reste dp in like manner, to the end that the one may

relieve the other, and when the first is wearie another taketh his place.”

easily have reached the Stobhall side) he turned and swam back, after which he galloped

away out o f sight. What struck me as most curious was the way in which he carried

himself during this swimming feat, the forepart o f the body being depressed almost below

the surface o f the water, while the stern appeared above it. The more he used his hind legs,

the lower went his head, dipping down at every stroke; so how the creature could escape

drowning in anything like rough water is more than I can say.

Roe I have frequently seen swim, and am convinced that at such times their

immersion in the water is deeper than that o f almost any other animal. The whole o f the

•body and most o f the neck are submerged, the head alone being carried well clear o f the

water, and all the higher when forging forward under the influence o f fear or excitement.

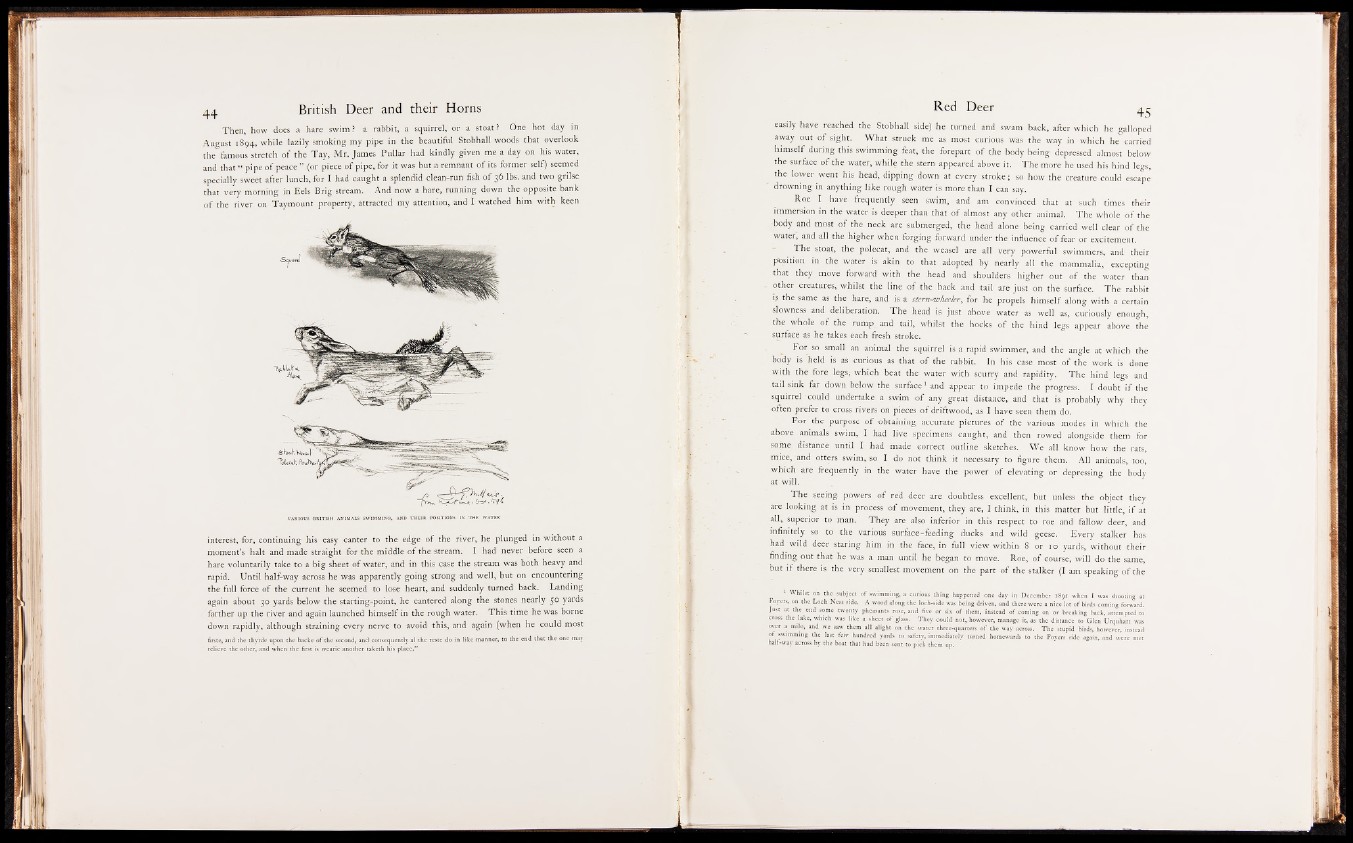

T h e stoat, the polecat, and the weasel are all very powerful swimmers, and their

position in the water is akin to that adopted by nearly all the mammalia, excepting

that they move forward with the head and shoulders higher out o f the water than

, other creatures, whilst the line o f the back and tail are just on the surface. The rabbit

is the same as the hare, and is a stern-wheeler, for he propels himself along with a certain

slowness and deliberation. The head is just above water as well as, curiously enough,

the whole o f the rump and tail, whilst the hocks o f the hind legs appear above the

surface as he takes each fresh stroke.

For so small an animal the squirrel is a rapid swimmer, and the angle at which the

body is held is as curious as that o f the rabbit. In his case most o f the work is done

with the fore legs; which beat the water with scurry and rapidity. The hind legs and

tail sink far down below the surface1 and appear to impede the progress. I doubt i f the

squirrel‘ could undertake a swim o f any great distance, and that is probably why they

often prefer to cross rivers on pieces o f driftwood, as I have seen them do.

For the purpose o f obtaining accurate pictures o f the various modes in which the

above animals swim, I had live specimens caught, and then rowed alongside them for

some distance until I had made correct outline sketches. We all know how the rats,

mice, and otters swim, so I do not think it necessary to figure them. All animals, too,

which are frequently in the water have the power o f elevating or depressing the body

at will.

The seeing- powers o f red deer are doubtless excellent, but unless the object they

are looking at is in process o f movement, they are, I think, in this matter but little, i f at

all, superior to man. They are also inferior in this respect to roe and fallow deer, and

infinitely so to the various surface-feeding ducks and wild geese. Every stalker has

had wild deer staring him in the face, in full view within 8 or io yards, without their

finding out that he was a man until he began to move. Roe, o f course, will do the same,

but i f there is the very smallest movement on the part o f the stalker (I am speaking o f the

1 Whilst on the subject of swimming, a curious thing happened one day in December 1891 when I was shooting at

Foyers, on the Loch Ness side. A wood along the loch-side was being driven, and there were a nice lot of birds coming forward.

Just at the end some twenty pheasants rose, and live or six of them, instead of coming on or breaking back, attempted to

cross the lake, which was like a sheet of glass. They could not, however, manage it, as the distance to Glen Urquhart was

over .a mile, and we saw them all alight on the water three-quarters of the way across. The stupid birds, however, instead

of swimming the last few hundred yards to safety, immediately turned homewards to the Foyers side again, and were met

half-way across by the boat that had been sent to pick them up.