. Charles Palk Collyns, the Dulverton surgeon who hunted with the Devon and Somerset

staghounds for no less than forty-six years, has given us by far the best account o f the wild

English deer that has yet been written. On page 57 o f his excellent book, The Chase o f the

W ild Red Deer, he says, speaking o f his own experience—

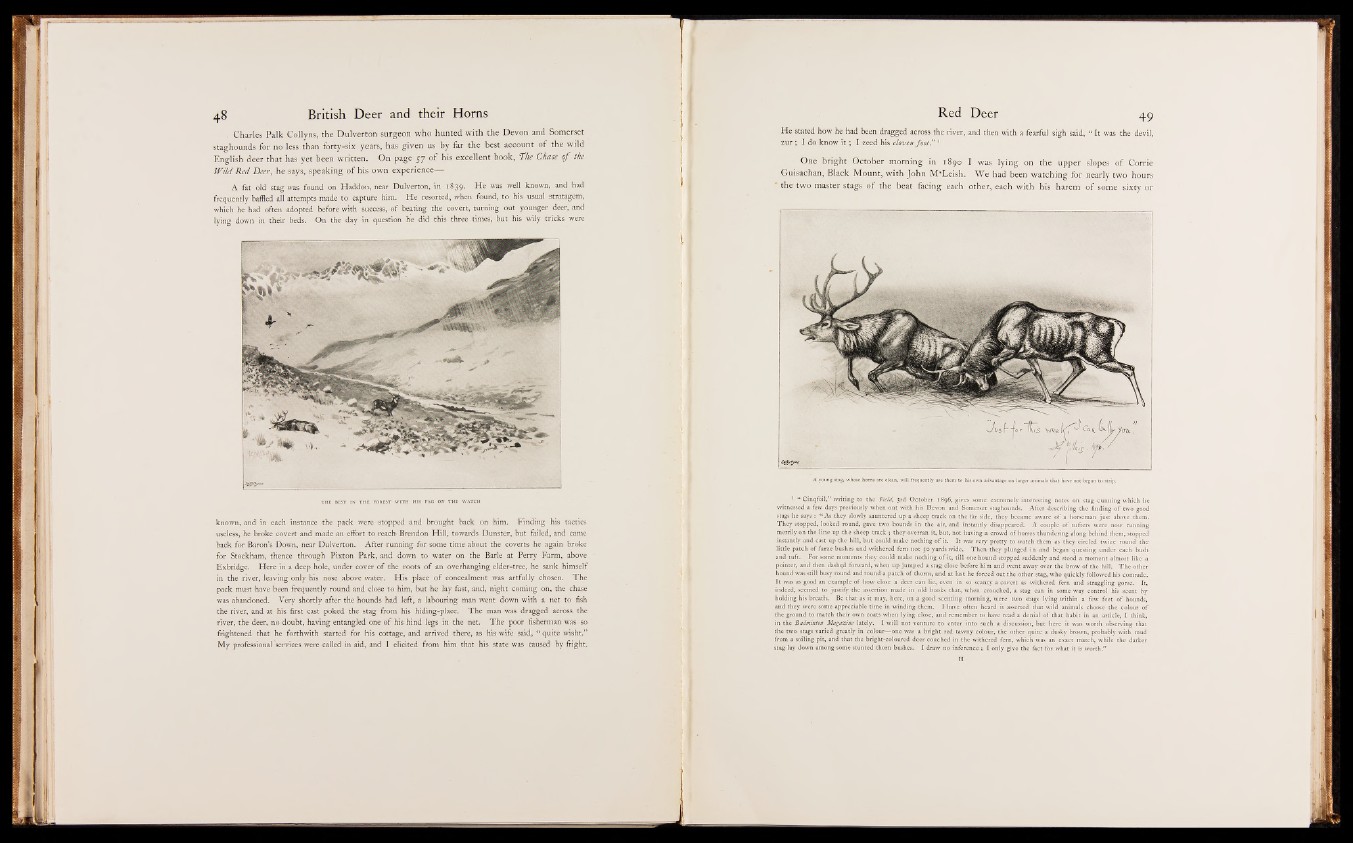

A fat old stag was found on Haddon, near Dulverton, in 1839- H e was well known, and had

frequently baffled all attempts made to capture him. He resorted, when found, to his usual stratagem,

which he had often adopted before with success, o f beating the covert, turning out younger deer, and

lying down in their beds. On the day in question he did this three times, but his wily tricks were

known, and in each instance the pack were stopped and brought back on him. Finding his tactics

useless, he broke covert and made an effort to reach' Brendon Hill, towards Dunster, but failed, and came

back for Baron’s Down, near Dulverton. After running for some time about the coverts he again broke

for Stockham, thence through Pixton Park, and down to water on the Barle at Perry Farm, above

Exbridge. Here in a deep hole, under cover o f the roots o f an overhanging elder-tree, he sank himself

in the river, leaving only his nose above water. His place o f concealment was artfully chosen. The

pack must have been frequently round and close to him, but he lay fast, and, night coming on, the chase

was abandoned. Very shortly after the hounds had left, a labouring man went down with a net to fish

the river, and at his first cast poked the stag from his hiding-place. The man was dragged across the

river, the deer, no doubt, having entangled one o f his hind legs in the net. The poor fisherman was so

frightened that he forthwith started for his cottage, and arrived there, as his wife said, “ quite wisht.”

My professional services were called in aid, and I elicited from him that his state was caused by fright.

He stated how he had been dragged across the river, and then with a fearful sigh said, “ It was the devil,

zur ; I do know i t ; I zeed his cloven fo o t ' ' 1

One bright October morning in 1890 I was lying on the upper slopes o f Corrie

Guisachan, Black Mount, with John M ‘Leish. We had been watching for nearly two hours

the two master stags o f the beat facing each other, each with his harem o f some sixty or

V “ Cinqfoil,” writing to the Field, 3rd October 1896, gives some extremely interesting notes on stag cunning which he

witnessed a few days previously when out with his Devon and Somerset staghounds. After describing the finding of two good

stags he says : “ As they slowly sauntered up a sheep track on the far side, they became aware of a horseman just above them.

They stopped, looked round, gave two bounds in the air, and instantly disappeared. A couple o f tufters were now running

merrily on the line up the'sheep track ; they overran it, but, not having a crowd of horses thundering along behind them, stopped

instantly and cast up the hill, but could make nothing o f it. It was very pretty to watch them as they circled twice round the

little patch of furze bushes and withered fern not 50 yards wide. Then they plunged in and began questing under each bush

and tuft. For some moments they could make nothing of it, till one hound stopped suddenly and stood a moment almost like a

pointer, and then dashe.d forward, when up jumped a stag close before him and went away over the brow o f the hill. The other

hound was still busy round and round a patch of thorns* and at last he forced out the other stag, who quickly followed his comrade.

It was as good an example of how close a deer can lie, even in so scanty a covert as withered fern and straggling gorse. It,

indeed, seemed to justify the assertion made in old books that, when crouched, a stag can in some way control his scent by

holding his breath. Be that as it may, here, on a good scenting morning, were two stags lying within a few feet of hounds,

and they were some appreciable time in winding them. I have often heard it asserted that wild animals choose the colour of

the ground to match their own coats when lying close, and remember to have read a denial of that habit in an article, I think,

in the Badminton Magazine lately. I will not venture to enter into such a discussion, but here it was worth observing that

the two stags varied greatly in colour— one was a bright red tawny colour, the other quite a dusky brown, probably with mud

from a soiling pit, and that the bright-coloured deer couched in the withered fern, which was an exact match, while the darker

stag lay down among some stunted thorn bushes. I draw no inference ; I only give the fact for what it is worth.”

H