ri

■IV'

il: .!

£ r

ÌÌ; '

to :&!

f (.1 ii 'tf''

toll

I. r

ii

commenced at pressures up to tbree to four tons on

the square inch.

Tbis last class of errors may seem very trivial, but

tbere are cases, vrbere questions of special delicacy

arise, in wbicli tbey may assume considerable importance.

Througbout the ocean generally, at all events

between the two polar circles, the temperature of the

ocean may be said as a rule to sink from the surface

to the hottom. There are many places however

where tbis gradual sinking appears to be arrested at

a certain point, from Avhich the temperature remains

uniform to the bottom. Frequently the temperatnre

as recorded by the thermometer reaches a minimum

at a depth of 1,800 or 2,000 fathoms : this is the

case, for example, throughout the greater part of the

Atlantic, and there is little doubt that the result is

in the main correct, and can be accounted for by tbe

action of a very simple law ; but if the temperature

remained exactly the same tlie application of tbis ultimate

correction to depths from 2,000 down to 3,000

fathoms would cause the thermometer to appear to

rise sensibly. This certainly is not generally the

case, or it would have come ont in the large number

of observations which hai'e heen made under circumstances

Avhere such a result might have been expected

; and therefore I think we must conclude that

in all the great ocean basins, from some cause or

other, tbere is a very slight fall of temperature to

the very hottom.

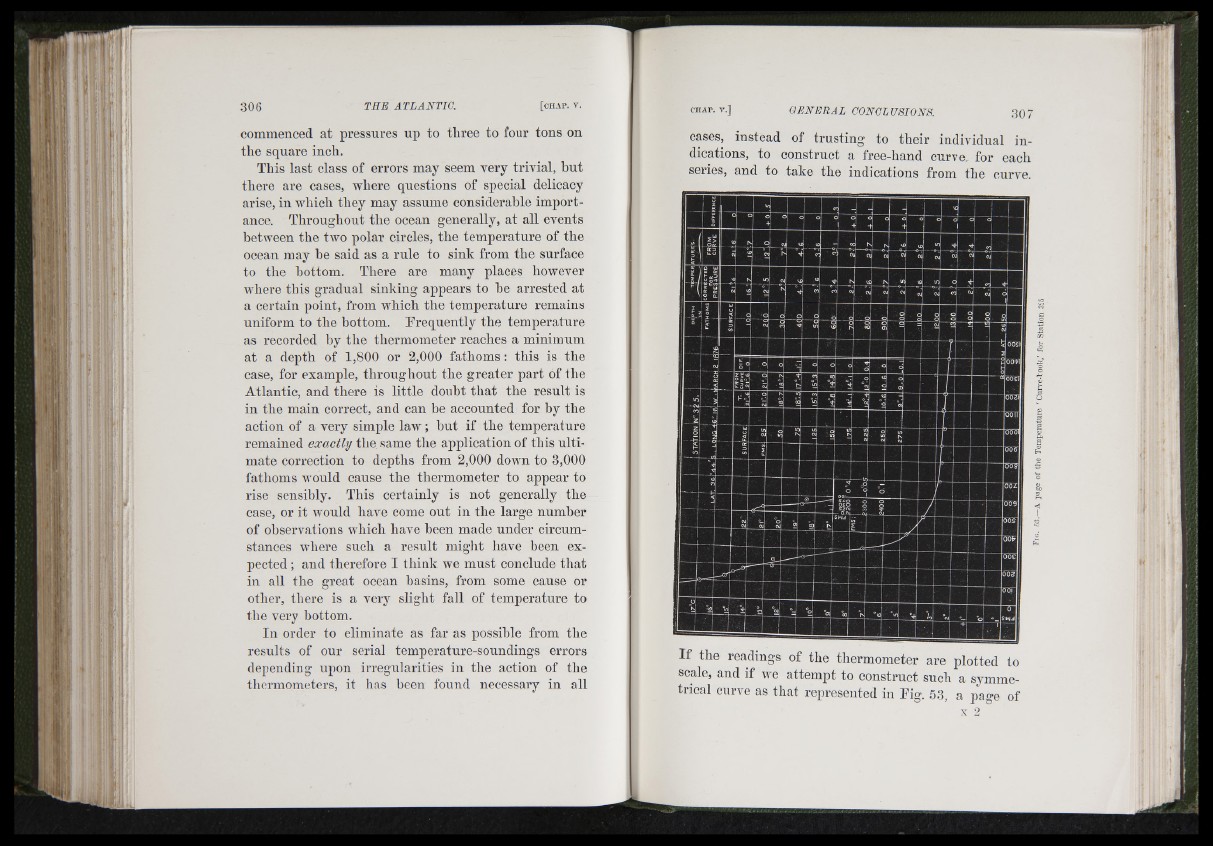

In order to eliminate as far as possible from the

results of onr serial temperature-soundings errors

depending upon irregularities in the action of the

thermometers, it has been found necessary in all

cases, instead of trusting to their individual indications,

to construct a free-hand curve for each

series, and to take the indications from the curve.

I f the readings of the thermometer are plotted to

scale, and if we attempt to construct such a symmetrical

curve as that represented in Fig. 53, a page of

\- 2

irl