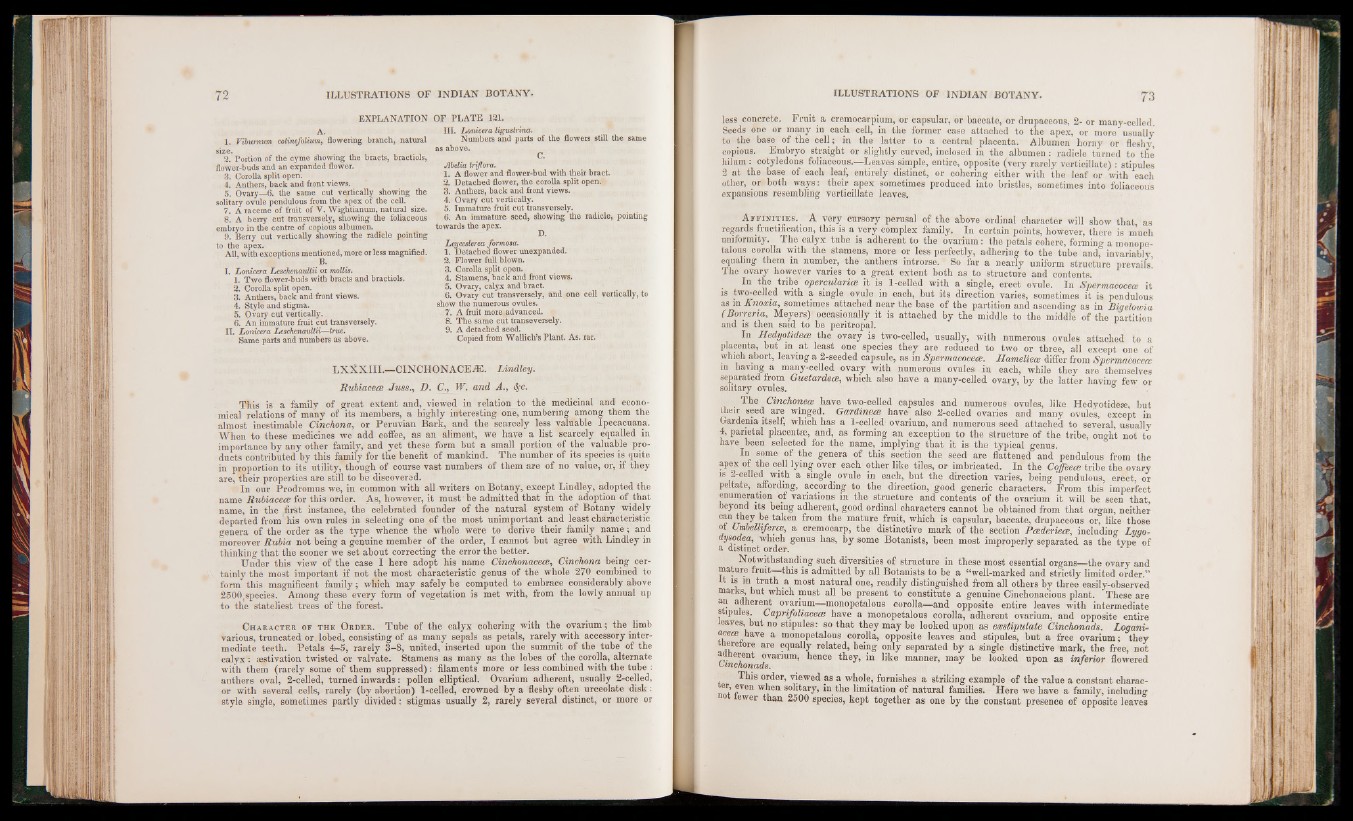

EXPLANATION

A.

1. Viburnum cotinefolium, flowering branch, natural

size. . -

2. Portion of the cyme showing the bracts, bractiols,

flower-buds and an expanded flower.

3. Corolla split open.

4. Anthers, back and front views.

5. Ovary—6. the same cut vertically showing the

solitary ovule pendulous from the apex of the cell.

7. A raceme of fruit of V. Wightianum, natural size.

8. A berry cut transversely, snowing the foliaceous

embryo in the centre of copious albumen.

9. Berry cut vertically showing the radicle pointing

to the apex.

All, with exceptions mentioned, more or less magnified.

B.

I. Lonicera Leschenaultii or mollis.

1. Two flower-buds with bracts and bractiols.

2. Corolla split open.

3. Anthers, back and front views.

4. Style and stigma.

5. Ovary cut vertically.

6. An immature fruit cut transversely.

II. Lonicera Leschenaultii—true.

Same parts and numbers as above.

OF PLATE 121.

III. Lonicera ligustrina.

Numbers and parts of the flowers still the same

as above.

C.

Abelia triflora.

1. A flower and flower-bud with their bract.

2. Detached flower, the corolla split open.

3. Anthers, back and front views.

4. Ovary cut vertically.

5. Immature fruit cut transversely.

6. An immature seed, showing the radicle, pointing

towards the apex.

D.

Leycesterea formosa.

1. Detached flower unexpanded.

2. Flower full blown.

3. Corolla split open.

4. Stamens, back and front views.

5. Ovary, calyx and bract.

6. Ovary cut transversely, and one cell vertically, to

show the numerous ovules.

7. A fruit more advanced.

8. The same cut transeversely.

9. A detached seed.

Copied from Wallich’s Plant. As. rar.

LX X X III.—CINCH ON ACEAE. Lindley.

Rubiacece Juss., D. C., W. and A., <$*c.

This is a family of great extent and, viewed in relation to the medicinal and economical

relations of many of its members, a highly interesting one, numbering among them the

almost inestimable Cinchona, or Peruvian Bark, and the scarcely less valuable Ipecacuana.

When to these medicines we add coffee, as an aliment, we have a list scarcely equalled in

importance by any other family, and yet these form but a small portion of the valuable products

contributed by this family for the benefit of mankind. The number of its species is quite

in proportion to its utility, though of course vast numbers of them are of no value, or, if they

are, their properties are still to be discovered.

In our Prodromus we, in common with all writers on Botany, except Lindley, adopted the

name Rubiacece for this order. As, however, it must be admitted that in the adoption of that

name, in the first instance, the celebrated founder of the natural system of Botany widely

departed from his own rules in selecting one of the most unimportant and least characteristic

genera of the order as the type whence the whole were to derive their family name; and

moreover Rubia not being a genuine member of the order, I cannot but agree with Lindley in

thinking that the sooner we set about correcting the error the better.

Under this view of the case I here adopt his name Cinchonacece, Cinchona being certainly

the most important if not the most characteristic genus of the whole 270 combined to

form this magnificent family; which may safely be computed to embrace considerably above

2500 species. Among these every form of vegetation is met with, from the lowly annual up

to the stateliest trees of the forest.

Character of the Order. Tube of the calyx cohering with the ovarium; the limb

various, truncated or. lobed, consisting of as many sepals as petals, rarely with accessory intermediate

teeth. Petals 4-5, rarely 3-8, united, inserted upon the summit of the tube of the

calyx: aestivation twisted or valvate. Stamens as many as the lobes of the corolla, alternate

with them (rarely some of them suppressed): filaments more or less combined with the tube :

anthers oval, 2-celled, turned inwards: pollen elliptical. Ovarium adherent, usually 2-celled,

or with several cells, rarely (by abortion) 1-celled, crowned by a fleshy often urceolate disk:

style single, sometimes partly divided: stigmas usually 2, rarely several distinct, or more or

less concrete. Fruit a cremocarpium, or capsular, or baccate, or drupaceous, 2- or many-celled.

Seeds one or many in each cell, in the former case attached to the apex, or moreusually

to the base of the cell ; in the latter to a central placenta. Albumen horny or fleshy,

copious. Embryo straight or slightly curved, inclosed in the albumen: radicle turned to the

hilum : cotyledons foliaceous.—Leaves simple, entire, opposite (very rarely verticillate) : stipules

2 at the base of each leaf, entirely distinct, or cohering either with the leaf or with each

other, or both ways: their apex sometimes produced into bristles, sometimes into foliaceous

expansions resembling verticillate leaves.

regards fructification, this is a very complex family. In certain points, however, there is much

uniformity. The calyx tube is adherent to the ovarium: the petals cohere, forming a monopetalous

corolla with the stamens, more or less perfectly, adhering to the tube and, invariably

equaling them in number, the anthers introrse. So far a nearly uniform structure prevails.

The ovary however varies to a great extent both as to structure and contents.

In the tribe opercularice it is 1-celled with a single, erect ovule. In Spermacocece it

is two-celled with a single ovule in each, but its direction varies, sometimes it is pendulous

as m Knoocia, sometimes attached near the base of the partition and ascending as in Bigelowia

( Borreria., Meyers) occasionally it is attached by the middle to the middle of the partition

and is then said to be peritropal.

In Hedyotidece the ovary is two-celled, usually, with numerous ovules attached to a

placenta, but in at least one species they are reduced to two or three, all except one of

which abort, leaving a 2-seeded capsule, as in Spermacocece. Hameliece differ from Spermacocece

in having a many-celled ovary with numerous ovules in each, while they are themselves

separated from Guetardece, which also have a many-celled ovary, by the latter having few* or

solitary ovules. °

The Cinchonece have two-celled capsules and numerous ovules, like Hedyotidese, but

their seed are winged. Gardinece have also 2-oelled ovaries and many ovules, except in

Gardenia itself, which has a 1-celled ovarium, and numerous seed attached to several, usually

4, parietal placentae, and, as forming an exception to the structure of the tribe, ought not to

have been selected for the name, implying that it is the typical genus.

In some of the genera of this section the seed are flattened and pendulous from the

apex of the cell lying over each other like tiles, or imbricated. In the Coffeece tribe the ovary

is 2-celled with a single ovule in each, but the direction varies, being pendulous, erect, or

peltate, affording, according to the direction, good generic characters. From this imperfect

enumeration of variations in the structure and contents of the ovarium it will be seen that,

beyond its being adherent, good ordinal characters cannot be obtained from that organ, neither

c^n ^key be taken from the mature fruit, which is capsular, baccate, drupaceous or, like those

ot Umbelliferce, a cremocarp, the distinctive mark of the section Pcederiece, including Lygo-

aysodea, which genus has, by some Botanists, been most improperly separated as the type of

a distinct order. J

Notwithstanding such diversities of structure in these most essential organs—the ovary and

mature fruit this is admitted by all Botanists to be a “well-marked and strictly limited order.”

is in truth a most natural one, readily distinguished from all others by three easily-observed

marks, but which must all be present to constitute a genuine Cinchonacious plant. These are

an adherent ovarium—monopetalous corolla—and opposite entire leaves with intermediate

s ipules. Caprifoliacece have a monopetalous corolla, adherent ovarium, and opposite entire

eaves, but no stipules: so that they may be looked upon as eoastipulate Cinchonads. Logani-

ace« have a monopetalous corolla, opposite leaves and stipules, but a free ovarium; they

eretore are equally related, being only separated by a single distinctive mark, the free, not

ScAow f/ Varmm’ kence they, in like manner, may be looked upon as inferior flowered

This order, viewed as a whole, furnishes a striking example of the value a constant charac-

r,’ ?ven w“en solitary, in the limitation of natural families. Here we have a family, including

o tewer than 2500 species, kept together as one by the constant presence of opposite leaves