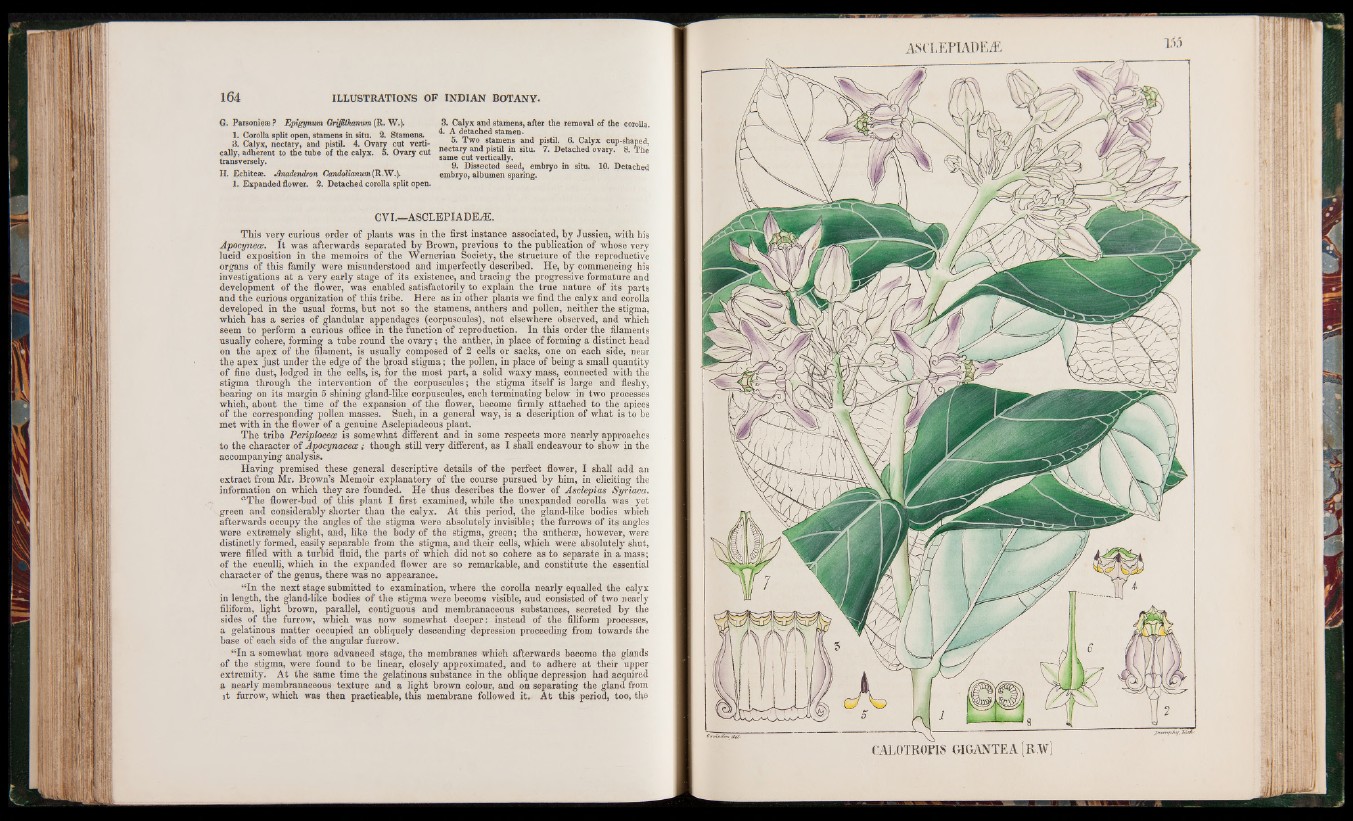

G. Parsonie® ? Epigynum GriffUkanum (R. W.).

1. Corolla split open, stamens in situ. 2. Stamens.

3. Calyx, nectary, and pistil. 4. Ovary cut vertically,

adherent to the tube of the calyx. 5. Ovary cut

transversely.

H. Echiteae. Anadendron Candolianum[R.W.).

1. Expanded flower. 2. Detached corolla split open.

3. Calyx and stamens, after the removal of the corolla.

4. A detached stamen.

5. Two stamens and pistil. 6. Calyx cup-shaped,

nectary and pistil in situ. 7. Detached ovary. 8. The

same cut vertically.

9. Dissected seed, embryo in situ. 10. Detached

embryo, albumen sparing.

CVI.—ASCLEPIADE^E.

This very curious order of plants was in the first instance associated, by Jussieu, with his

Apocynece. I t was afterwards separated by Brown, previous to the publication of whose very

lucid exposition in the memoirs of the Wernerian Society, the structure of the reproductive

organs of this family were misunderstood and imperfectly described. He, by commencing his

investigations at a very early stage of its existence, and tracing the progressive formature and

development of the flower, was enabled satisfactorily to explain the true nature of its parts

and the curious organization of this tribe. Here as in other plants we find the calyx and corolla

developed in the usual forms, but not so the stamens, anthers and pollen, neither the stigma,

which has a series of glandular appendages (corpuscules), not elsewhere observed, and which

seem to perform a curious office in the function of reproduction. In this order the filaments

usually cohere, forming a tube round the ovary; the anther, in place of forming a distinct head

on the apex of the filament, is usually composed of 2 cells or sacks, one on each side, near

the apex just under the edge of the Inroad stigma; the pollen, in place of being a small quantity

of fine dust, lodged in the cells, is, for the most part, a solid waxy mass, connected with the

stigma through the intervention of the corpuscules; the stigma itself is large and fleshy,

bearing on its margin 5 shining gland-like corpuscules, each terminating below in two processes

which, about the time of the expansion of the flower, become firmly attached to the apices

of the corresponding pollen masses. Such, in a general way, is a description of what is to be

met with in the flower of a genuine Asclepiadeous plant.

The tribe Periphceae is somewhat different and in some respects more nearly approaches

to the character of Apocynaceae; though still very different, as I shall endeavour to show in the

accompanying analysis.

Having premised these general descriptive details of the perfect flower, I shall add an

extract from Mr. Brown’s Memoir explanatory of the course pursued by him, in eliciting the

information on which they are founded. He thus describes the flower of Asclepias Syriaca.

“The flower-bud of this plant I first examined, while the unexpanded corolla was yet

green and considerably shorter than the calyx. At this period, the gland-like bodies which

afterwards occupy the angles of the stigma were absolutely invisible; the furrows of its angles

were extremely slight, and, like the body of the stigma, green; the antheras, however, were

distinctly formed, easily separable from the stigma, and their cells, which were absolutely shut,

were filled with a turbid fluid, the parts of which did not so cohere as to separate in a mass;

of the cuculli, which in the expanded flower are so remarkable, and constitute the essential

character of the genus, there was no appearance.

“In the next stage submitted to examination, where the corolla nearly equalled the calyx

in length, the glandrlike bodies of the stigma were become visible, aud consisted of two nearly

filiform, light brown, parallel, contiguous and membranaceous substances, secreted by the

sides of the furrow, which was now somewhat deeper: instead of the filiform processes»

a gelatinous matter occupied an obliquely descending depression proceeding from towards the

base of each side of the angular furrow.

“In a somewhat more advanced stage, the membranes which afterwards become the glands

of the stigma, were found to be linear, closely approximated, and to adhere at their upper

extremity. At the same time the gelatinous substance in the oblique depression had acquired

a nearly membranaceous texture and a light brown colour, and on separating the gland from

it furrow, which was then practicable, this membrane followed it. At this period, too, the

ASCLEPIADEÆ

CAL0TR0PIS GIGANTEA[R.W)