on sticks of Oleander used as spits. The leaves of, what appears to me, Wrightia tinctoria

are, I learn, employed in Mangalore as an effectual remedy in cases of toothache. The fresh

leaves are well chewed, and being very pungent, speedily act as a powerful sialogogue, which

quickly and effectually removes the pain. 1 have not yet had an opportunity of ascertaining

whether the fresh leaves are thus pungent, but I find that the dried ones, sent for inspection,

have lost much of that property in drying, and with it I presume their virtues. Holarrhena

antidysenterica, a very common and handsome flowering shrub on the Malabar coast, has been

long held in repute on that coast, on account of the astringent and tonic properties of its bark,

which is prescribed both to cure fevers and arrest bowel complaints; the seed also, having been

first slightly toasted, are prescribed, in infusion, in slighter forms of bowel complaint. The

roots of Ichnocarpus frutescens, in common with those of Hemidesmus indica, are currently

employed in European hospitals under the name of country Sarsaparilla. The wood of Alstonia

scholaris, a common Indian tree, is as bitter as Gentian, and possessed of somewhat similar

properties; and the roots of Ophioooylon Serpentinum, so called with reference to its reputed

antidotal powers in cases of snake bite, are certainly tonic, and are supposed to act on the

uterine system somewhat in the manner of Ergot of rye. While the tendency to the production

of poisonous and acrid secretions, is thus the predominating characteristic of the order,

we find some remarkable exceptions to the rule. The cow tree of Guiana, a species of

Tabernimontana yields, when wounded, a copious stream of thick, sweet, wholesome milk; so

also the juice of some species of Cerbera lose the venomous qualities found in the fruit of

others of that genus. The juice of Urceola elastica, furnishes a fine Caoutchouc, as does

that of several others, but of inferior quality. The leaves of Wrightia tinctoria furnish an

Indigo of excellent quality in very considerable abundance. As regards the timber of the

arborious forms little seems to be known, probably owing to few of them attaining a large size.

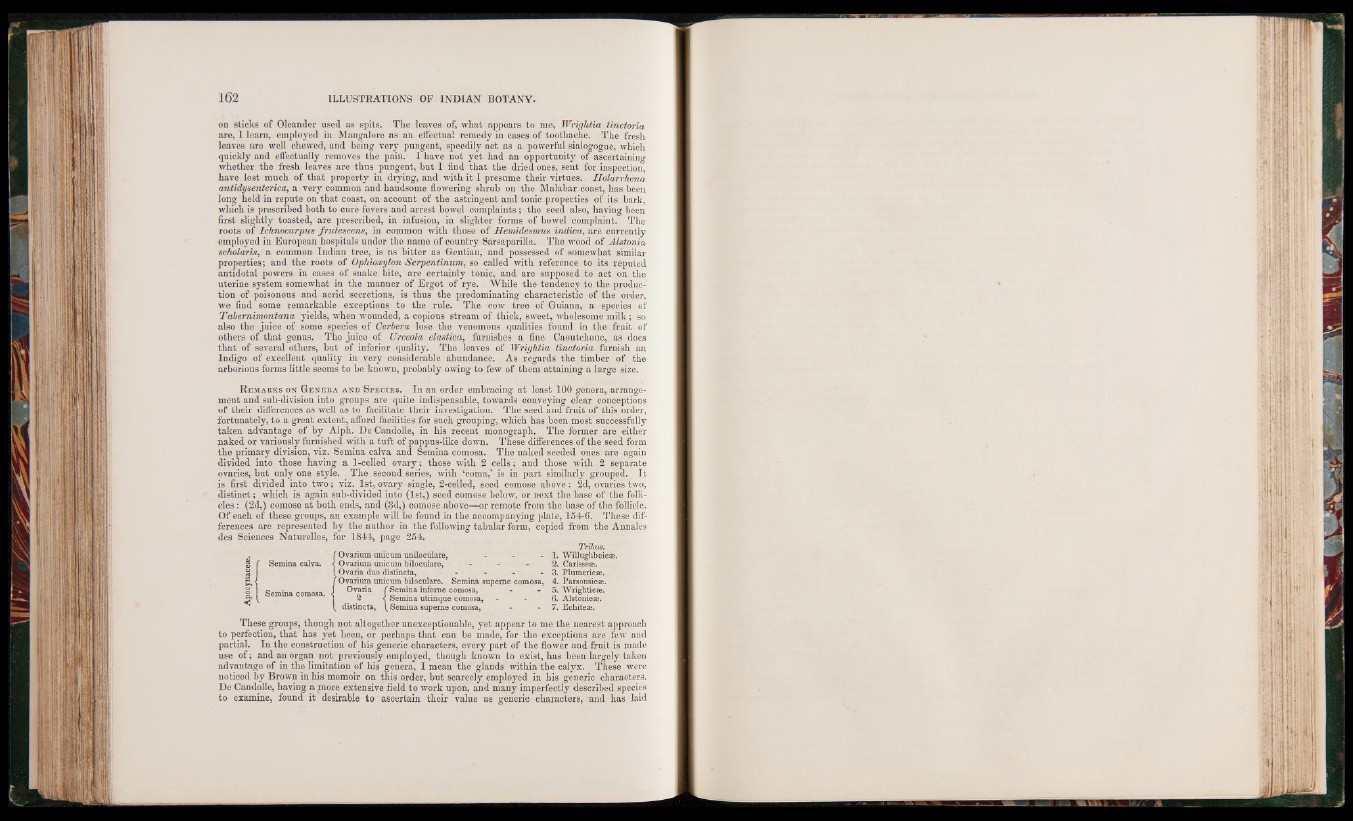

Remarks on Genera and Species. In an order embracing at least 100 genera, arrangement

and sub-division into groups are quite indispensable, towards conveying clear conceptions

of their differences as well as to facilitate their investigation. The seed and fruit of this order,

fortunately, to a great extent, afford facilities for such grouping, which has been most successfully

taken advantage of by Alph. De Candolle, in his recent monograph. The former are either

naked or variously furnished with a tuft of pappus-like down. These differences of the seed form

the primary division, viz. Semina calva and Semina comosa. The naked seeded ones are again

divided into those having a 1-celled ovary; those with 2 cells; and those with 2 separate

ovaries, but only one style. The second series, with ‘coma,’ is in part similarly grouped. It

is first divided into two; viz. 1st, ovary single, 2-celled, seed comose above: 2d, ovaries two,

distinct; which is again sub-divided into (1st,) seed comose below, or next the base of the follicles

: (2d,) comose at both ends, and (3d,) comose above—or remote from the base of the follicle.

Of each of these groups, an example will be found in the accompanying plate, 154-6. These differences

are represented by the author in the following tabular form, copied from the Ahnales

des Sciences Naturelles, for 1844, page 254.

Semina comosa. ! Ovarium unicum uniloculare, -

Ovarium unicum biloculare, -

Ovaria duo distincta, - - - • -

Ovarium unicum biloculare. Semina supeme comosa,

Ovaria f Semina infeme comosa,

. 2 ^ Semina utrinque comosa,

( distincta, ( Semina supeme comosa,

Tribus.

1. Willughbeieæ.

2. Carisseæ.

3. Plumerieæ.

4. Parsonsieæ.

5. Wrightieæ.

6. Alstonieæ.

7. Echiteæ.

These groups, though not altogether unexceptionable, yet appear to me the nearest approach

to perfection, that has yet been, or perhaps that can be made, for the exceptions are few and

partial. In the construction of his generic characters, every part of the flower and fruit is made

use of; and an organ not previously employed, though known to exist, has ;been largely taken

advantage of in the limitation of his genera, I mean the glands within the calyx. These were

noticed by Brown in his memoir on this order, but scarcely employed in his generic characters.

De Candolle, having a .more extensive field to work upon, and many imperfectly described species

to examine, found it desirable to ascertain their value as generic characters, and has laid