CAMPANULINEAE.

Passing from the Epigynous, Monospermous group of Aggregatse, including Valerianae,

Dipsacea, and Composita, we enter upon the consideration of a new series of Epigynous

families, differing from the preceding in having several-celled ovaries with numerous ovules.

These have been associated under the above name, as being more nearly allied to each other

than to any other families. They were, in the first instance, combined into one order by

Jussieu, under the name of Campanulacese. From this Brown separated Goodenoviea and

Stylidiece, and indicated Brunoniacea as the type of a new Order: but retained Lobeliacea as

a section of Campa/nulacea, in which he has been followed by Alph. De Candolle and Arnott.

Bartling, however, considered that section entitled to rank as a distinct order, and has been followed

by all subsequent writers. He, at the same time, grouped these orders into a class, which

he designated Campanulinje, which has been adopted by Endlicher and Meisner.

As a single order, the plants associated in this class would assuredly form a somewhat

heterogeneous assemblage, but notwithstanding they all appear so nearly related that I should

not be surprised to see several of these families reunited and reduced to the rank of sub-orders,

which, while they served all the purposes of practical convenience, would I think prove more

in accordance with the principles of a natural arrangement, the object of which is to form

circular groups, linked together by few but comprehensive characters. Of this description

Endlicher’s character of his “class” Campanulinse may be taken as an example:

“Herbs or shrubs, rarely arborious. Leaves alternate or opposite. Stipules none. Flowers

bisexual, inflorescence various. Tube of the calyx adherent to the ovary, with the limb superior,

rarely free. Corolla perigynous or rarely hypogynous, regular or irregular. Stamens inserted

with the corolla, sometimes scarcely distinct from it. Ovary rarely 1-celled, usually several-

celled. Ovules rarely definite and erect from the base, very often numerous, ascending, ana-

tropous, attached to central placentae. Fruit capsular, baccate, or nucamentaceous, 1- or

many-seeded. Seed albuminous, rarely exalbuminous. Embryo central, orthotropous radicle

inferior.”

The plants embraced within this character are all nearly related to each other by numerous

intermediate characters, while they present various points of relationship with surrounding

orders, which, however, are more or less weakened by sub-division into so many independent

families. Sub-division is however indispensable to enable us to grapple with the host of species

it includes; but it still remains a question to be solved by the researches of the Philosophical

Botanist, whether these sub-divisions ought to retain the rank of independent families or of suborders.

This question it is not my intention to examine, as it would lead me into details incompatible

with the object of this work, which is rather to place before the Indian Botanist a view

of the science as it now exists, than to attempt innovations, which I have neither the means nor

leisure to work out to a satisfactory conclusion.

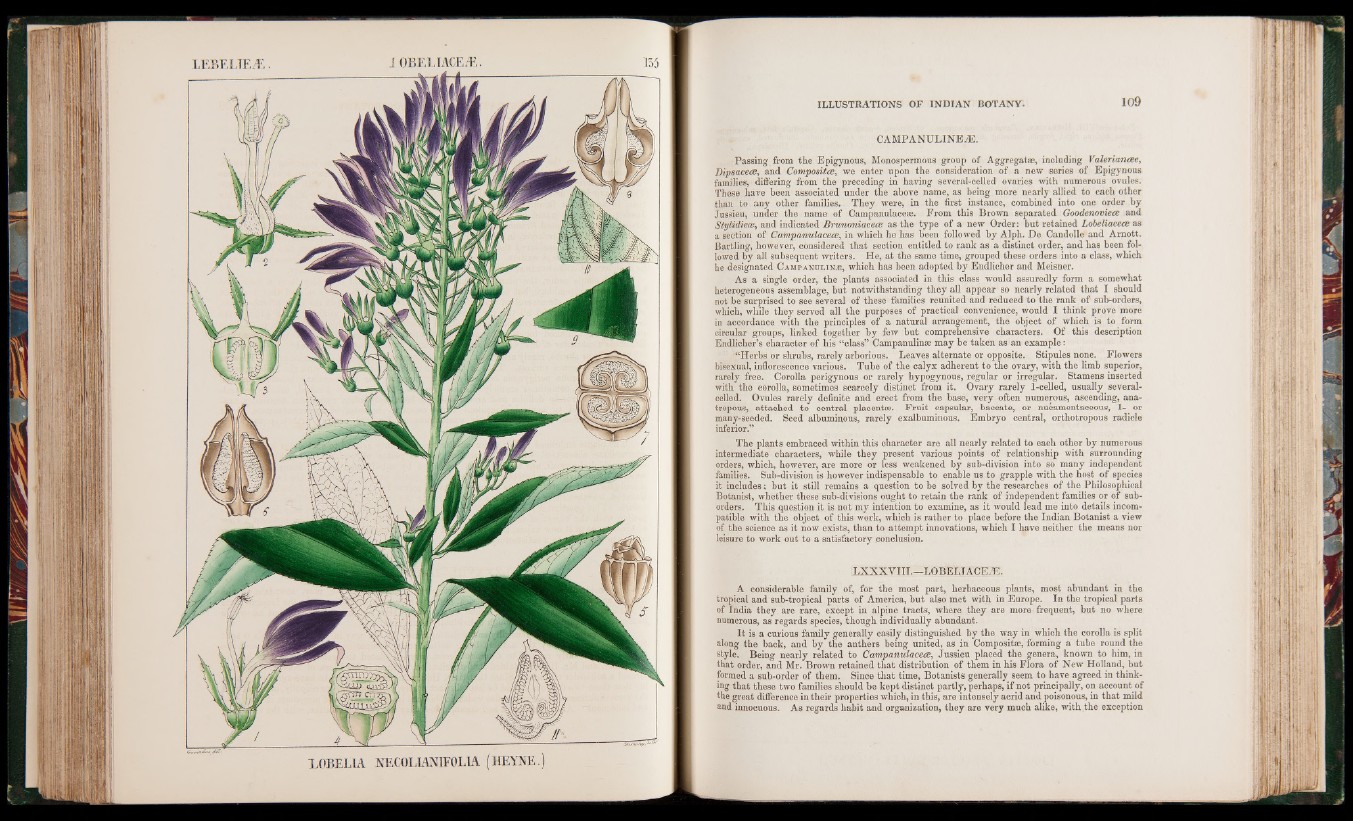

LXXXYIII.—LOBELIACEiE.

A considerable family of, for the most part, herbaceous plants, most abundant in the

tropical and sub-tropical parts of America, but also met with in Europe. In the tropical parts

of India they are rare, except in alpine tracts, where they are more^ frequent, but no where

numerous, as regards species, though individually abundant.

I t is a curious family generally easily distinguished by the way in which the corolla is split

along the back, and by the anthers being united, as in Composite, forming a tube round the

style. Being nearly related to Campanulacea, Jussieu placed the genera, known to him, in

that order, and Mr. Brown retained that distribution of them in his Flora of New Holland, but

formed a sub-order of them. Since that time, Botanists generally seem to have agreed in thinking

that these two families should be kept distinct partly, perhaps, if not principally, on account of

the great difference in their properties which, in this, are intensely acrid and poisonous, in that mild

and innocuous. As regards habit and organization, they are very much alike, with,the exception