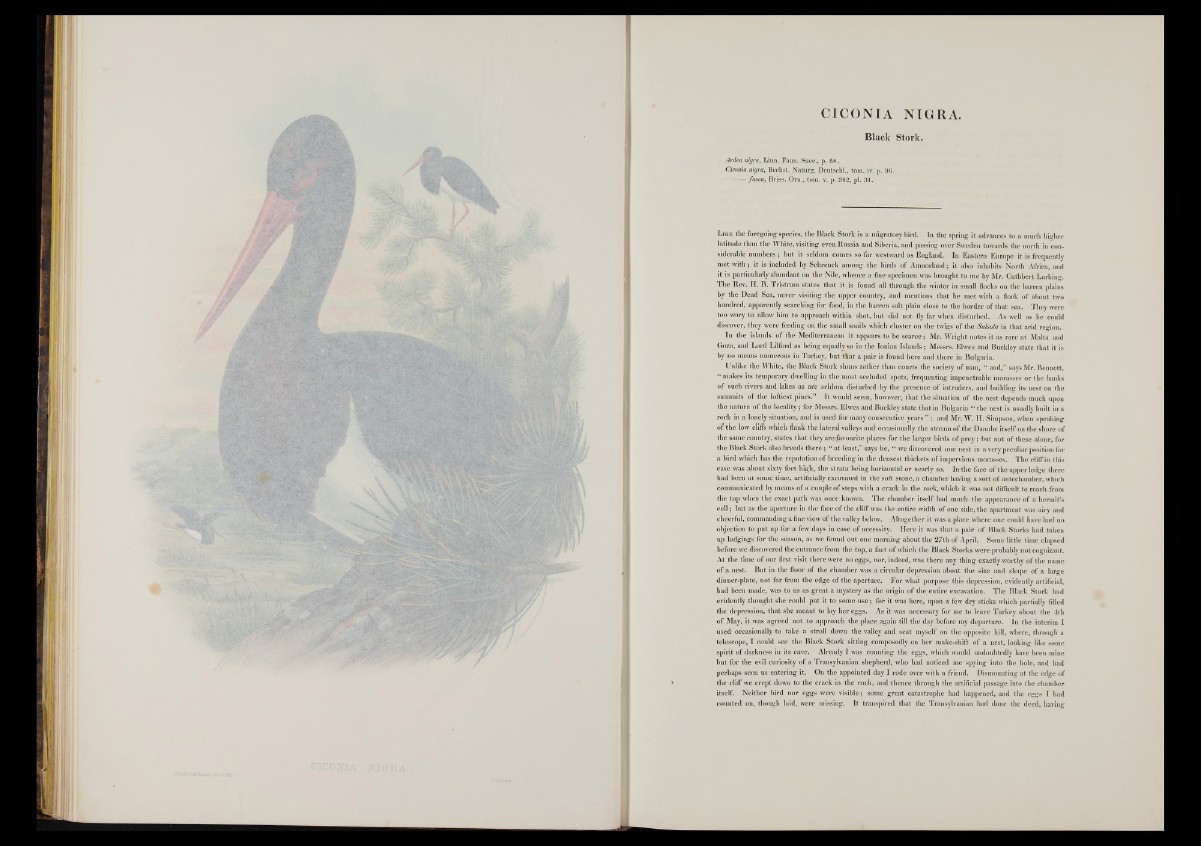

CICONIA NIGRA.

Black Stork.

Ardea nigra, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 58,

Ciconia nigra, Bechst. Naturg. Deutschl., tom. iv. p. 96.

—- ■ fusca, Briss. Om., tom. v. p. 362, pi. 31.

L ik e the foregoing species, the Black Stork is a migratory bird. In the spring it advances to a much higher

latitude than the White, visiting even Russia and Siberia, and passing over Sweden towards the north in considerable

numbers ; but it seldom comes so far westward as England. In Eastern Europe it is frequently

met w ith ; it is included by Schrenck among the birds o f Amoorland; it also inhabits North Africa, and

it is particularly abundant ou the Nile, whence a fine specimen was brought to me by Mr. Cuthbert Larking.

The Rev. H. B. Tristram states th at it is found all through the winter in small flocks on the barren plains

by the Dead Sea, never visiting the upper country, and mentions that he met with a flock of about two

hundred, apparently searching for food, in the barren salt plain close to the border o f that sea. They were

too wary to allow him to approach within shot, but did not fly far when disturbed. As well as he could

discover, they were feeding on the small snails which cluster on the twigs o f the Salsola in that arid region.

In the islands o f the Mediterranean it appears to be scarce ; Mr. Wright notes it as rare a t Malta and

Gozo, and Lord Lilford as being equally so in the Ionian Islands; Messrs. Elwes and Buckley state that it is

by no means numerous in Turkey, but th at a pair is found here and there in Bulgaria.

Unlike the White, the Black Stork shuns rather than courts the society of man, “ and,” says Mr. Bennett,

“ makes its temporary dwelling in the most secluded spots, frequenting impenetrable morasses or the banks

o f such rivers and lakes as ai*e seldom disturbed by the presence of intruders, and building its nest on the

summits o f the loftiest pines. * I t would seem, however, tnat the situation of the nest depends much upon

the nature o f the locality; for Messrs. Elwes and Buckley state th at in Bulgaria “ the nest is usually built in a

rock in a lonely situation, and is used for many consecutive years ” : and Mr. W . H. Simpson, when speaking

of the low cliffs which flank the lateral valleys and occasionally the stream o f the Danube itself on the shore of

the same country, states that they arejfavourite places for the larger birds o f prey; but not of these alone, for

the Black Stork also breeds th e re ; “ a t least,” says he, “ we discovered one nest in a very peculiar position for

a bird which has the reputation o f breeding in the densest thickets of impervious morasses. The cliff in this

case was about sixty feet high, the strata being horizontal or nearly so. In the face of the upper ledge there

had been a t some time, artificially excavated in the soft stone, a chamber having a sort o f antechamber, which

communicated by means o f a couple o f steps with a crack in the rock, which it was not difficult to reach from

the top when the exact path was once known. The chamber itself had much the appearance o f a hermit’s

cell; but as the aperture in the face of the cliff was the entire width o f one side, the apartment was airy and

cheerful, commanding a fine view of the valley below. Altogether it was a place where one could have had no

objection to put up for a few days in case o f necessity. Here it was that a pair of Black Storks had taken

up lodgings for the season, as we found out one morning about the 27th of April. Some little time elapsed

before we discovered the entrance from the top, a fact o f which the Black Storks were probably not cognizant.

At the time o f our first visit there were no eggs, nor, indeed, was there any thing exactly worthy o f the name

o f a nest. But in the floor of the chamber was a circular depression about the size and shape o f a large

dinner-plate, not far from the edge of the aperture. F o r what purpose this depression, evidently artificial,

had been made, was to us as great a mystery as the origin of the entire excavation. The Black Stork had

evidently thought she could put it to some u se ; for it was here, upon a few dry sticks which partially filled

the depression, that she meant to lay her eggs. As it was necessary for me to leave Turkey about the 4th

o f May, it was agreed not to approach the place again till the day before my departure. In the interim I

used occasionally to take a stroll down the valley and seat myself on the opposite hill, where, through a

telescope, I could see the Black Stork sitting composedly on her make-shift o f a nest, looking like some

spirit of darkness in its cave. Already I was counting the eggs, which would undoubtedly have been mine

but for the evil curiosity of a Transylvanian shepherd, who had noticed me spying into the hole, and had

perhaps seen us entering it. On the appointed day I rode over with a friend. Dismounting at the edge of

the cliff we crept down to the crack in the rock, and thence through the artificial passage into the chamber

itself. Neither bird nor eggs were visible; some great catastrophe had happened, and the eggs I had

counted on, though laid, were missing. I t transpired that the Transylvanian had done the deed, having