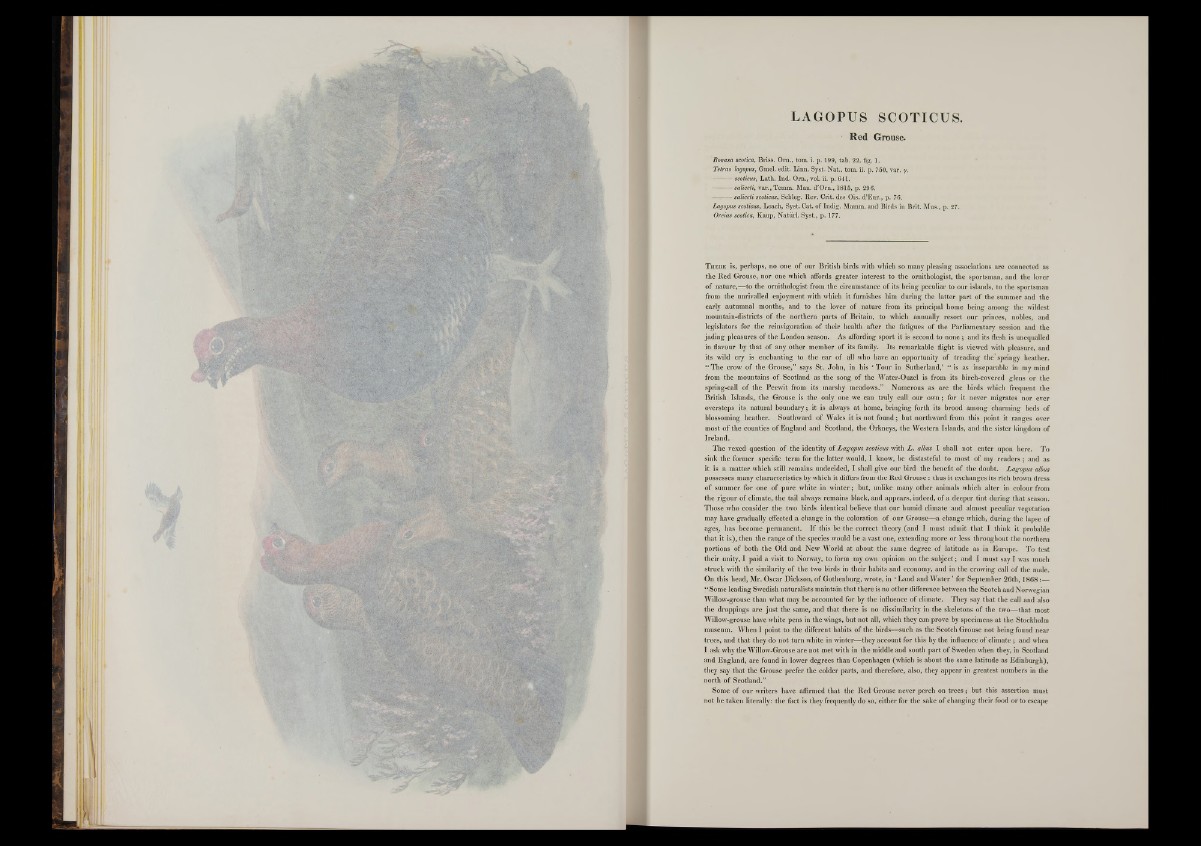

Red Grouse.

Bonasa scotica, Briss. Orn., tom. i. p. 199, tab. 22. fig. 1.

Tetrao lagopus, Gmel. edit. Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. ii. p. 750, var. y.

scoticus, Lath. Ind. Ora., vol. ii. p. 641.

saliceti, var., Temm. Man. d’Orn., 1815, p. 296.

saliceti scoticus, Schleg. Rev. Crit. des Ois. d’Eur., p. 76.

Lagopus scoticus, Leach, Syst. Cat. of Indig. Mamm. and Birds in Brit. Mus., p. 27.

Oreias scotica, Kaup, Naturi. Syst., p. 177.

T h e r e is, perhaps, no one o f our British birds with which so many pleasing associations are connected as

the Red Grouse, nor one which affords greater interest to the ornithologist, the sportsman, and the lover

o f nature,—to the ornithologist from the circumstance of its being peculiar to our islands, to the sportsman

from the unrivalled enjoyment with which it furnishes him during the latter part of the summer and the

early autumnal months, and to the lover of nature from its principal home being among the wildest

mountain-districts o f the northern parts o f Britain, to which annually resort our princes, nobles, and

legislators for the reinvigoration of their health after the fatigues of the Parliamentary session and the

jading pleasures of the London season. As affording sport it is second to none ; and its flesh is unequalled

in flavour by that o f any other member o f its family. Its remarkable flight is viewed with pleasure, and

its wild cry is enchanting to the ear of all who have an opportunity of treading th e ’springy heather.

“ The crow o f the Grouse,” says St. John, in his ‘ Tour in Sutherland/ “ is as inseparable in my mind

from the mountains of Scotland as the song o f the Water-Ouzel is from its birch-covered glens or the

spring-call o f the Peewit from its marshy meadows.” Numerous as are the birds which frequent the

British Islands, the Grouse is the only one we can truly call our own ; for it never migrates nor ever

oversteps its natural boundary; it is always a t home, bringing forth its brood among charming beds of

blossoming heather. Southward o f Wales it is not found; but northward from this point it ranges over

most o f the counties of England and Scotland, the Orkneys, the Western Islands, and the sister kingdom of

Ireland.

The vexed question of the identity o f Lagopus scoticus with L . albus I shall not enter upon here. To

sink the former specific term for the latter would, I know, be distasteful to most o f my read ers; and as

it is a matter which still remains undecided, I shall give our bird the benefit of the doubt. Lagopus albus

possesses many characteristics by which it differs from the R ed G rouse: thus it exchanges its rich brown dress

o f summer for one o f pure white in win ter; but, unlike many other animals which alter in colour from

the rigour o f climate, the tail always remains black, and appears, indeed, o f a deeper tint during that season.

Those who consider the two birds identical believe that our humid climate and almost peculiar vegetation

may have gradually effected a change in the coloration o f our Grouse—a change which, during the lapse of

ageSj has become permanent. If this be the correct theory (and I must admit that I think it probable

that it is), then the range o f the species would be a vast one, extending more or less throughout the northern

portions o f both the Old and New World a t about the same degree of latitude as in Europe. To test

their unity, I paid a visit to Norway, to form my own opinion on the subject; and I must say I was much

struck with the similarity o f the two birds in their habits and economy, and in the crowing call o f the male.

On this head, Mr. Oscar Dickson, of Gothenburg, wrote, in ‘ Land and Water ’ for September 26th, 1868:—

“ Some leading Swedish naturalists maintain that there is no other difference between the Scotch and Norwegian

Willow-grouse than what may be accounted for by the influence o f climate. They say that the call and also

the droppings are just the same, and that there is no dissimilarity in the skeletons of the two—that most

Willow-grouse have white pens in the wings, but not all, which they can prove by specimens a t the Stockholm

museum. When I point to the different habits o f the birds—such as the Scotch Grouse not being found near

trees, and that they do not turn white in winter—they account for this by the influence o f climate; and when

I ask why the Willow-Grouse are not met with in the middle and south p a rt o f Sweden when they, in Scotland

and England, are found in lower degrees than Copenhagen (which is about the same latitude as Edinburgh),

they say that the Grouse prefer the colder parts, and therefore, also, they appear in greatest numbers in the

north o f Scotland/’

Some o f our writers have affirmed that the Red Grouse never perch on tre e s ; but this assertion must

not be taken literally: the fact is they frequently do so,'either for the sake o f changing their food or to escape