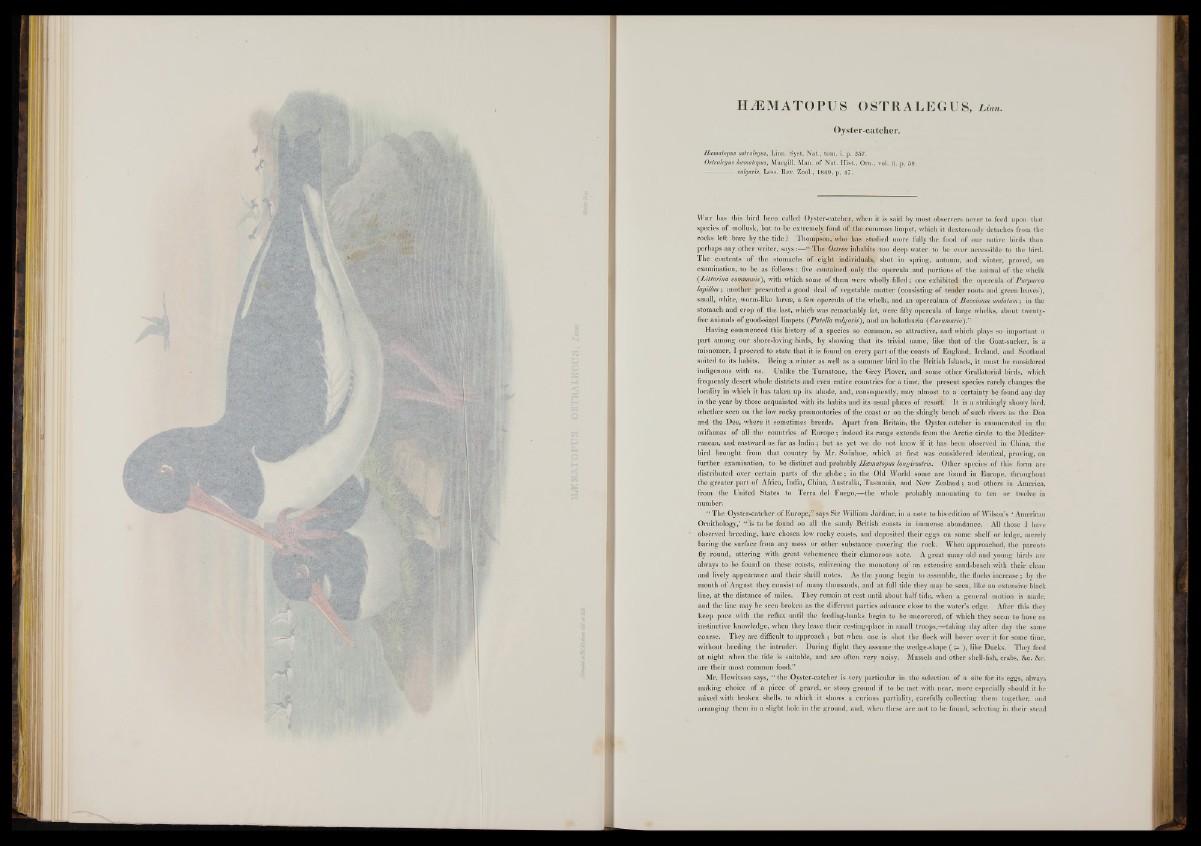

HJEMATOPUS OSTRALEGU S, Linn.

Oyster-catcher.

Hamatopus ostralegus, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 257.

Ostralegus hamatopus, Macgill. Man. of Nat. Hist., Orn., vol. ii. p. 59.

— vulgaris, Less. Rev. Zool., 1849, p. 47.

W hy has this bird been called Oyster-catcher, when it is said by most observers never to feed upon that

species o f mollusk, but to be extremely fond o f the common limpet, which it dexterously detaches from the

rocks left bare by the tide ? Thompson, who has studied more fully the food of our native birds than

perhaps any other writer, says:— “ The Ostrea inhabits too deep water to be ever accessible to the bird.

T he contents o f the stomachs of eight, individuals, shot in spring, autumn, and winter, proved, on

examination, to be as follows: five contained only 'th e opercula and portions of the animal of the whelk

(Littonna con0finis'), with which some of them were wholly filled; one exhibited the opercula of Purpurea

lapillus ; another presented a good deal o f vegetable matter (consisting of tender roots and green leaves),

small, white, worm-like larvae, a few opercula o f the whelk, and an operculum of Buccitium undatum; in the

stomach and crop o f the last, which was remarkably fat, were fifty opercula. of large whelks, about twenty-

five animals of good-sized limpets ( Patella vulgaris), and an holothuria ( Cucumaria) .”

Having commenced this history of a species so common, so attractive, and which plays so important a

part emong 0ur shore-loving birds, by showing that its trivial name, like that of the Goat-sucker, is a

misnomer, I proceed to state that it is found on every p art of the coasts o f England, Ireland, and Scotland

suited to its habits. Being a winter as well as a summer bird in the British Islands, it must be considered

indigenous with us. Unlike the Turnstone, the Grey Plover, and some other Grallatorial birds, which

frequently desert whole districts and even entire countries for a time, the present species rarely changes the

locality in which it has taken up its abode, and, consequently, may almost to a certainty be found any day

in the year by those acquainted with its habits and its usual places of resoifi It is a strikingly showy bird,

whether seen on the low rocky promontories of the coast or on the shingly beach of such rivers as the Don

and the Dee, where it sometimes breeds:. Apart from Britain, the Oyster-catcher is enumerated in the

avifaunas of all the countries o f E u ro p e; indeed its range extends from the Arctic circle to the Mediter-

ranean, and eastward as far as In d ia ; but as yet we do not know if if has been observed in China, the

bird brought from that country by Mr. Swinhoe, which a t first was considered identical, proving, on

further examination, to be distinct and probably Heematopus longirostris. Other species o f this form are

distributed over certain parts o f the globe; in the Old World some are found in Europe, throughout

the greater part o f Africa, India, China, Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand; and others in America,

from the United States to Terra del Fuego,—the whole probably amounting to ten or twelve in

number.

“ The Oyster-catcher o f Europe,” says S ir William Jardine, in a note to his edition of Wilson’s ‘ American

Ornithology,’ “ ¿s to be found on all the sandy British coasts in immense abundance. All those I have

observed breeding, have chosen low rocky coasts, and deposited their eggs on some shelf or ledge, merely

baring the surface from any moss or other substance covering the rock. When approached, the parents

fly round, uttering with great vehemence their clamorous note. A great many old and young birds are

always to be found on these coasts, enlivening the monotony o f an extensive sand-beach with their clean

and lively appearance and their shrill notes. As the young begin to assemble, the flocks increase; by the

month of August they consist of many thousands, and at full tide they may be seen, like an extensive black

line, a t the distance o f miles. They remain at rest until about half tide, when a general motion is made,

and the line may be seen broken as the different parties advance close to the water’s edge. After this they

keep pace with the reflux until the feeding-banks begin to be uncovered, o f which they seem to have an

instinctive knowledge, when they leave their resting-place in small troops,—taking day after day the same

course. They are difficult to approach ; but when one is shot the flock will hover over it for some time,

without heeding the intruder. During flight they assume the wedge-shape ( > • ), like Ducks. They feed

a t night when the tide is suitable, and are often very noisy. Mussels and other shell-fish, crabs, &c. &c.

are their most common food/’ .

Mr. Hewitson says, “ the Oyster-catcher is very particular in the selection of a site for its eggs, always

making choice of a piece of gravel, or stony ground if to be met with near, more especially should it be

mixed with broken shells, to which it shows a curious partiality, carefully collecting them together, and

arranging them in a slight hole in the ground, and, when these are not to be found, selecting in their stead