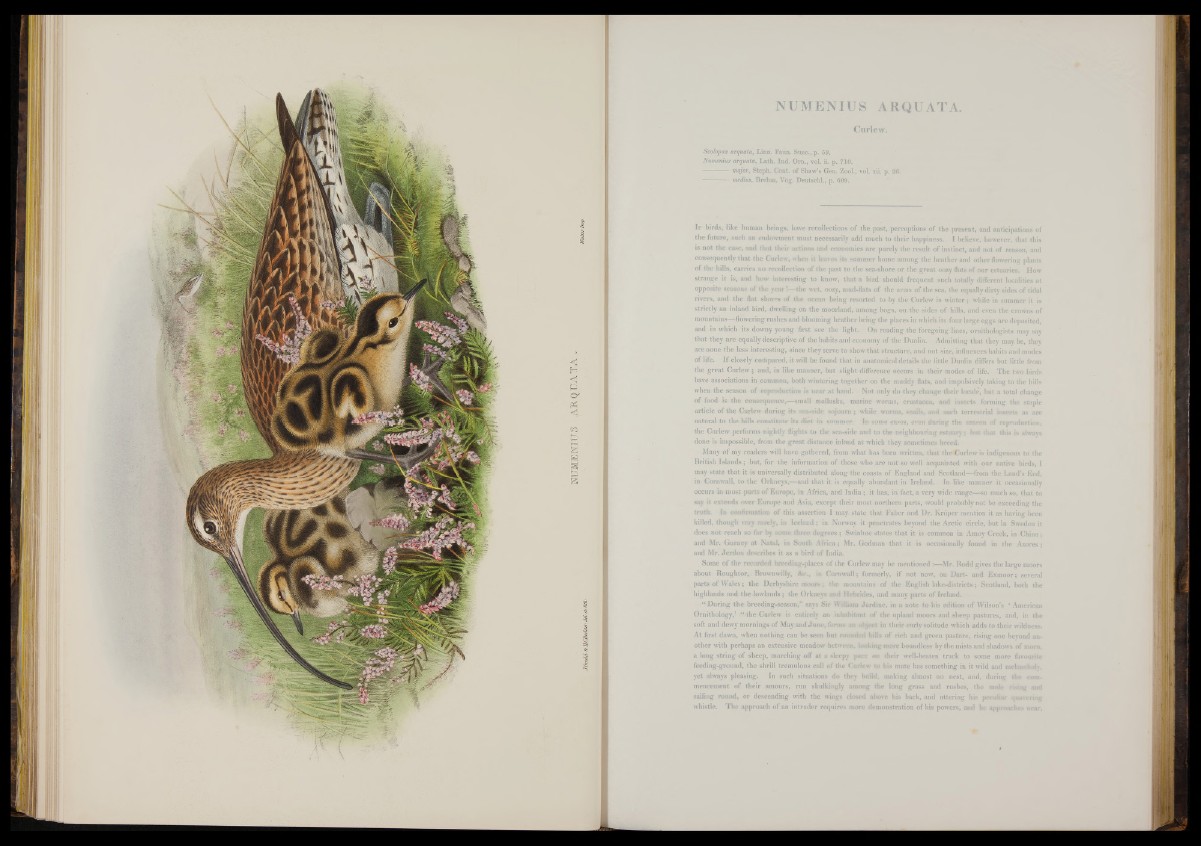

UHMENIUS : ARQJDAIA .

Curlew.

Scolopax arquata, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 59.

Numenius arquata. Lath. Ind. Om., vol. ii. p. 710.

major, Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xii. p. 26.

-----------medius, Brehm, Vog. Deutschl., p. 609.

Ip birds, like human beings, have recollections o f the past, perceptions of the present, and anticipations of

the future, such an endowment must necessarily add much to their happiness. I believe, however, that this

is not the ease, and that their actions and economies are purely the result of instinct, and not of reason, and

consequently that the Curlew, when it leaves its summer home among the heather and other flowering plants

o f the hills, carries no recollection of the past to the sea-shore or the great oozy flats o f our estuaries. How

strange it is, and how interesting to know, that a bird should frequent such totally different localities at

opposite seasons o f the y e a r!—the wet, oozy, mud-flats o f the arms of the sea, the equally dirty sides of tidal

rivers, and the flat shores of the ocean being resorted to by the Curlew in win ter; while in summer it is

strictly an inland bird, dwelling on the moorland, among bogs, on the sides o f hills, and even the crowns of

mountains—flowering rushes and blooming heather being the places in which its four large eggs are deposited,

and in which its downy young first see the light. On reading the foregoing lines, ornithologists may say

th at they are equally descriptive o f the habits and economy o f the Dunlin. Admitting that they may be, they

are none the less interesting, since they serve to show th at structure, and not size, influences habits aud modes

o f life. I f closely compared, it will be found that in anatomical details the little Dunlin differs but little from

the great Curlew; and, in like manner, but slight difference occurs in their modes o f life. The two birds

have associations in common, both wintering together on the muddy flats, and impulsively taking to the hills

when the season of reproduction is near at hand. Not only do they change their locale, but a total change

o f food is the consequence,—small raollusks, marine worms, Crustacea, and insects forming the staple

article o f the Curlew during its sea-side sojourn ; while worms, snails, and such terrestrial insects as are

natural to the hills constitute its diet in summer. In some cases, even during the season of reproduction,

the Curlew performs nightly flights to the sea-side and to the neighbouring estuaryj but that this is always

done is impossible, from the great distance inland at which they sometimes breed.

Many o f my readers will have gathered, from what has been written, that the Curlew is indigenous to the

British Islan d s; but, for the information of those who are not so well acquainted with our native birds, I

may state that it is universally distributed along the coasts of England and Scotland—from the Land’s End,

in Cornwall, to the Orkneys,—and that it is equally abundant in Ireland. In like manner it occasionally

occurs in most parts o f Europe, in Africa, and In d ia ; it has, in fact, a very wide range—so much so, that to

say it extends over Europe aud Asia, except their most northern parts, would probably not be exceeding the

truth, in confirmation o f this assertion I may state that Faber and Dr. Krtiper mention it as having been

killed, though very rarely, in Iceland; in Norway it penetrates beyond the Arctic circle, but in Sweden it

does not reach so far by some three deg re e s; Swinhoe states that it is common in Amoy Creek, in China;

and Mr. Gurney a t Natal, in South Africa; Mr. Godm an that it is occasionally found in the Azores ;

and Mr. Jerdon describes it as a bird o f India.

Some o f the recorded breediug-places of the Curlew may be mentioned :—Mr. Rodd gives the large moors

about Roughtor, Brownwilly, &<•., in Cornwall; formerly, if not now, on Dart- and Exmoor; several

parts o f Wales; the Derbyshire moors; the mountains o f the English lake-districts; Scotland, both the

highlands and the lowlands; the Orkneys avid Hebrides, and many parts of Ireland.

“ During the breeding-season,” says Sir William Jardine, in a note to his edition o f Wilson’s * American

Ornithology,’ “ the Curlew is entirely an inhabitant of the upland moors and sheep pastures, and, in the

soft and dewy m ornings o f May and Ju n e, forms an object in their early solitude which adds to their wildness.

At first dawn, when nothing can be seen but rounded hills o f rich and green pasture, rising one beyond another

with perhaps an extensive meadow between, looking more boundless by the mists and shadows o f morn,

a long string of sheep, marching off at a sleepy pace on their well-beaten track to some more favourite

feeding-ground, the shrill tremulous call of the Curlew to bis mate has something in it wild and melancholy,

yet always pleasing. In such situations do they build, making almost no nest, and, during the commencement

o f their amours, run skulkingly among the long grass and rushes, the male rising and

sailing round, o r descending with the wings closed above his back, and uttering his peculiar quaver tug

whistle. The approach o f an intruder requires more demonstration of his powers, and he approaches near,