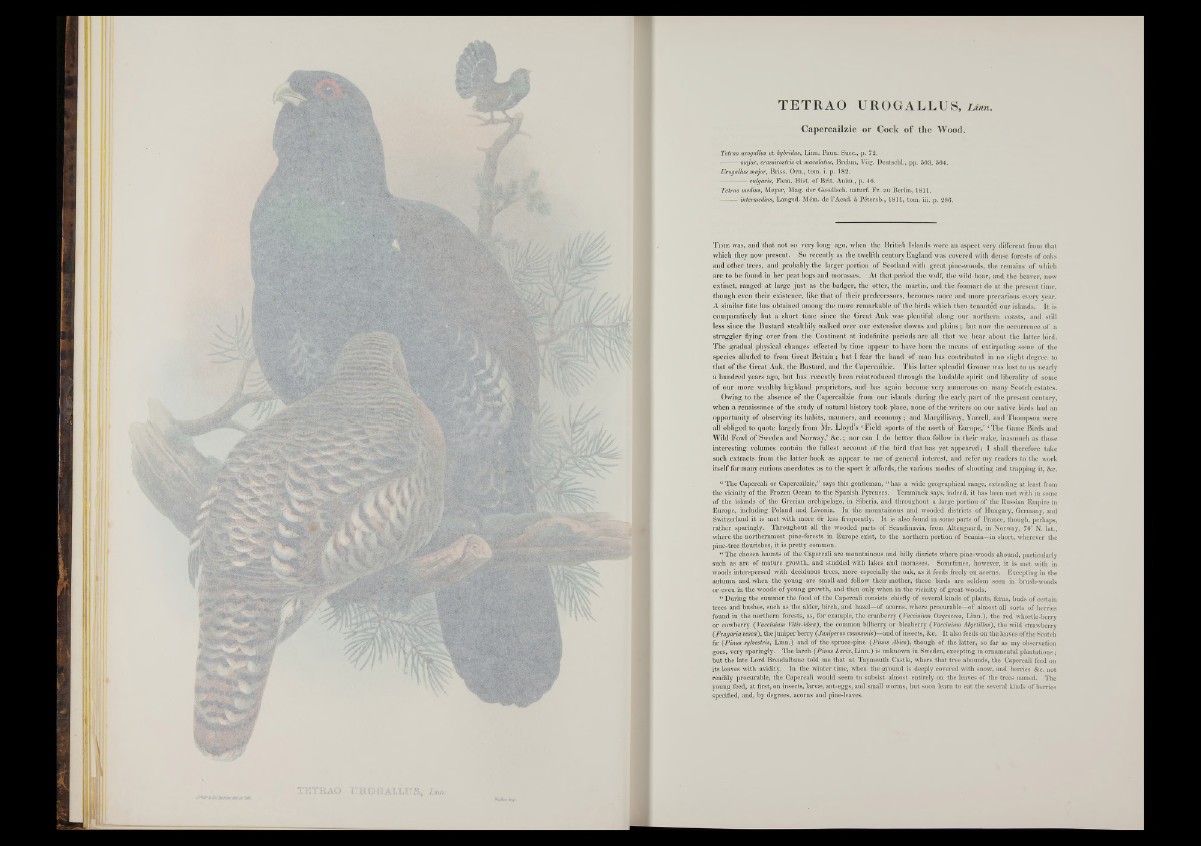

TETRAO UROGALLU S, JLinn.

Capercailzie or Cock of the Wood.

Tetrao urogalius et hybridus, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 72.

major, crassirostris et maculatus, Brehm, Vög. Deutsch!., pp. 503, 504.

Urogallus major, Briss. Om., tom. i.' p. 182.

vulgaris, Flem. Hist, of Brit. Anim., p. 46.

Tetrao medius, Meyer, Mag. der Gesellsch. naturf. Fr. zu Berlin, 1811.

intermedins, Langsd. Mem. de l’Acad. ä Pötersb., 1811, tom. iii. p. 286.

T im e was, and that not so very long ago, when the British Islands wore an aspect very different from that

which they now present. So recently as the twelfth century England was covered with dense forests of oaks

and other trees, and probably the larger portion of Scotland with great pine-woods, the remains of which

are to be found in her peat bogs and morasses. Al that period the wolf, the wild boar, and the beaver, now

extinct, ranged at large just as the badger, the otter, the martin, and the foumart do at the present time,

though even their existence, like that of their predecessors, becomes more and more precarious every year.

A similar fate has obtained among the more remarkable of the birds which then tenanted our islands. I t is

comparatively but a short time since the Great Auk was plentiful along our northern coasts, and still

less since the Bustard stealthily walked over our extensive downs and plains; but now the occurrence of a

straggler flying over from the Continent at indefinite periods are all that we hear about the latter bird.

The gradual physical changes effected by time appear to have been the means of extirpating some of the

species alluded to from Great Britain; but I fear the hand of man lias contributed in no slight degree to

that o f the Great Auk, the Bustard, and the Capercailzie. This latter splendid Grouse was lost to us nearly

a hundred years ago, but has recently been reintroduced through the laudable spirit and liberality of some

o f our more wealthy highland proprietors, and has again become very numerous on many Scotch estates.

Owing to the absence o f the Capercailzie from our islands during the early part of the present century,

when a renaissance o f the study of natural history took place, none of the writers on our native birds had an

opportunity of observing its habits, manners, and economy; and Macgillivray, Yarrell, and Thompson were

all obliged to quote largely from Mr. Lloyd’s ‘ Field sports of the north of Europe,’ I The Game Birds and

Wild Fowl of Sweden and Norway,’ &c.; nor can I do better than follow in their wake, inasmuch as those

interesting volumes contain the fullest account o f the bird that has yet appeared; I shall therefore take

such extracts from the latter book as appear to me of general interest, and refer my readers to the work

itself for many curious anecdotes as to the sport it affords, the various modes of shooting and trapping it, &c.

“ The Capercali or Capercailzie,” says this gentleman, “ has a wide geographical range, extending at least from

the vicinity of the Frozen Ocean to the Spanish Pyrenees. Temminck says, indeed, it has been met with in some

of the islands of the Grecian archipelago, in Siberia, and throughout a .large portion of the Russian Empire in

Europe, including Poland and Livonia. In the mountainous and wooded districts of Hungary, Germany, and

Switzerland it is met with more or less frequently. I t is also found in some parts of France, though, perhaps,

rather sparingly. Throughout all the wooded parts of Scandinavia, from Altengaard, in Norway, 70° N. lat.,

where the northernmost pine-forests in Europe exist, to the northern portion of Scania—in short, wherever the

pine-tree flourishes, it is pretty common.

“ The chosen haunts of the Capercali are mountainous and hilly disricts where pine-woods abound, particularly

such as are of mature growth, and studded with lakes and morasses. Sometimes, however, it is met with in

woods interspersed with deciduous trees, more especially the oak, as it feeds freely on acorns. Excepting in the

autumn and when the young are small and follow their mother, these birds are seldom seen in brush-woods

or even in the woods of young growth, and then only when in the vicinity of great woods.

“ During the summer the food of the Capercali consists chiefly of several kinds of plants, ferns, buds of certain

trees and bushes, such as the alder, birch, and hazel—of acorns, where procurable—of almost all sorts of berries

found in the northern forests, as, for example, the cranberry ( Vaccinium Oxycoccos, Linn.), the red whortle-berry

or cowberry (Vaccinium Vitis-idcea), the common bilberry or bleaberry (Vaccinium Myrtillus), the wild strawberry

(Fragaria vesca) , the juniper berry (Juniperus communis)—and of insects, &c. I t also feeds on the leaves of the Scotch

fir (Pinus sylvestris, Linn.) and of the spruce-pine (Pinus Abies), though of the latter, so far as my observation

goes, very sparingly. The larch (Pinus Larix, Linn.) is unknown in Sweden, excepting in ornamental plantations;

but the late Lord Breadalbane told me that at Taymouth Castle, where that tree abounds, the Capercali feed on

its leaves with avidity. In the winter time, when the ground is deeply covered with snow, and berries &c. not

readily procurable, the Capercali would seem to subsist almost entirely on the leaves of the trees named. The

young feed, at first, on insects, larvae, ant-eggs, and small worms, but soon learn to eat the several kinds of berries

specified, and, by degrees, acorns and pine-leaves.