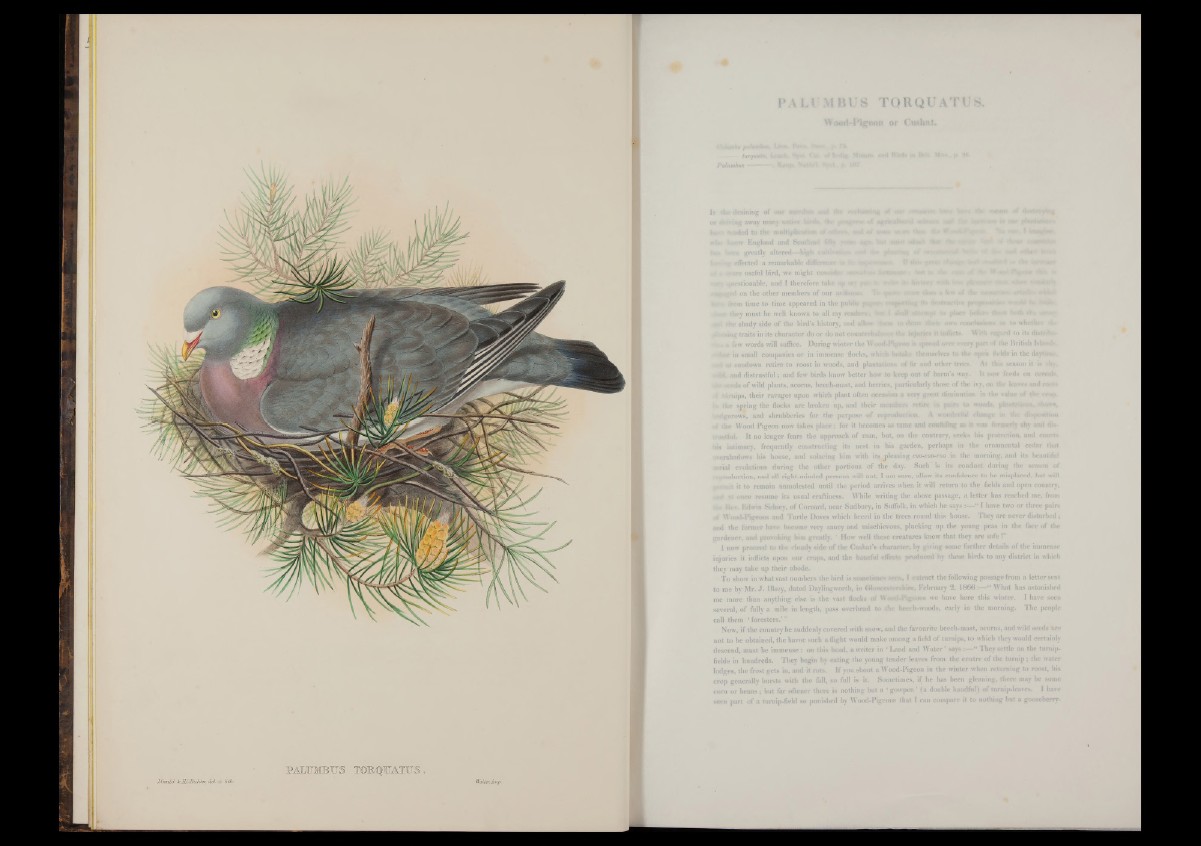

JGoulcL teJLCJkchta) d d / d> Uth/ WaJixr.Imp.

rQRQl

»!».<• fefttsw England and SooiWwt Wfer w«*» km mm* mlm& Wm. #

hw# greatly altered—high

»«¿ytst effected a remarkable differ»»*!*'m fa

«»are useful bird, we might consider SwtwiMtfe •> b*t M

• ••. questionable, and I therefore take up «fj g«* «•• 2#t» IliWttipy »itb PPWWW

s--v?;'-: At'd on the other members o f our avifewaw.

from time to time appeared in the pubhe mtffis&bt# it* destructive •:.,■■ «:« ■ *> mmm f a w ttb ,

■mmt 'hey must be well known to all my read ers; #»64 1 MW® '«t*e99»|it w place ihsfe* WMh- w t s m MIMMn

the shady side of the bird’s history, and allow to draw rfum own conelwwm* as to whether A

-!>ui traits in its character do o r do not count.cihafew.fflW the itmmcts. With regard to its datnwi-

** few words will suffice. During winter the WootWPtfpeoi* i* spread over every part <»f the British Is!«-!’ “■

in small companies or in immense flocks, which betake themselves to the open fields in the daytimv

;.f sundown retire to roost in woods, and plantations of fir and other trees. At this season it u shy,

v, •*>:■;. and distrustful; and few birds know better bow to keep out of harm’s way. It now feeds on cereals,

veds of wild plants, acorns, beech-mast, and berries, particularly those of the ivy, on the leaves and roof*

4 turnips, their ravages upon which plant often occasion a very great diminution in the value of crop.

the spring the flocks are broken up, and their member« retire eft pair*, to woods, ptotsfeftttM*, shaw«,

»«eilgerows, and shrubberies for the purpose of rcproouctkm?. A w'oowrhw change >*» t»c di*qw*ittofl

«ff the Wood Pigeon now takes place; for it becomes as tame and confiding as it was formerly «by awl distrustful.

I t no longer fears the approach of man, bat, on the contrary, seeks his protection, and court*

bis intimacy, frequently constructing its nest in his garden, perhaps in the ornamental cedar that

vversbadows his house, and solacing him with its pleasing coo-coo-roo in the morning, and its beautiful

; i-mal evolutions during the other portions of the day. Such is its conduct during the season ot.

reproduction, and all right-minded persons will not, I am sure, allow its confidence to be misplaced, but will

«KTWMt it to remain unmolested until the period arrives when it will return to the fields and open country,

ni once resume its usual craftiness. While writing the above passage, a letter has reached me, from

Hev. Edwin Sidney, of Comard, near Sudbury, in Suffolk, in which he says :— “ I have two or three pairs

,i Wood-Pigeons and Turtle Doves which breed in the trees round this house. They are never d isturbed;

and the former have become very saucy and mischievous, plucking up the young peas in the face of the

gardener, and provoking him greatly. How well these creatures know that they are sa fe !”

I now proceed to the cloudy side o f the Cushat’s character, by giving some further details o f the immense

injuries it inflicts upon our crops, and the baneful effects produced by these birds to any district in which

they may take up their abode.

To show in what vast numbers the bird is sometime*» I extract the following passage from a letter sent

to me by Mr. J . Illsey, dated Daylingworth, in Ohmcewtershire, February 2, 1866:— “ What has astonished

me more than anything else is the vast flocks o f Wood-Pigeons we have here this winter. I have seen

several, o f fully a mile in length, pass overhead to the hee< h-woods, early in the morning. The people

call them * foresters.’ ”

Now, if the country be suddenly covered with snow, and the favourite beech-mast, acorns, and wild seeds are

not to be obtained, the havoc such a flight would make among afield of turnips, to which they would certainly

descend, must be immense : on this bead, a writer in * Land and Water ’ says:—“ They settle on the turnip-

fields in hundreds. They begin by eating the young tender leaves from the centre o f the tu rn ip ; the water

lodges, the frost gets in, and it rots. If you.shoot a Wood-Pigeon in the winter when returning to roost, bis

crop generally bursts with the fall, so full is it. Sometimes, if he has been gleaning, there may be some

corn or beans ; but far oftener there is nothing but a ‘ gowpen ’ (a double handful) of turnip-leaves. I have

seen part of a turnip-field so punished by Wood-Pigeons that I can compare it to nothing but a gooseberry