hills where they dwell. The change is mainly effected by a moult of the feathers, and not by the colour

being absorbed or thrown out, as is the case to a certain extent with the Sandpipers; but on this subject, one

o f especial interest, Mr. Wheelwright, who has seen so much of the bird in its native haunts in Lapland,

shall have his say. I will only premise that the mutations which take place in the birds of that country

equally occur in those of our own.

“ The change from the winter to the summer dress is a true moult, and not a change of colour. It is

difficult to say what is the real summer dress of the Ptarmigan ; for they appear to be in a continual state of

change during the whole of that season, and to bear no one dress for any length of tim e ; so irregular is the

change that you scarcely ever see two exactly alike: on the same day in the end of July, you may kill some

in the early summer dress, and others with many blue autumn feathers. Up to the 9th of July all the old

males killed were brownish black on the back, speckled with lighter brown, especially 011 the head,

breast, and sides, the darkness of the breast being much more conspicuous in some than in o th ers ; belly

pure white. By the 20th the entire body had become much lig h ter; and by the end of the month was

changing to blue-grey, but still speckled with brown, especially on the head. By the 6th of August the males

had assumed a totally different d res s ; head still speckled with yellowish brown; back bluish grey, watered

with black and white; belly pure white. This blue-watered dress becomes of a fainter grey-blue until

the end of S eptember; but the white winter feathers gradually show themselves.

“ Much as the males vary in plumage, the females vary still more, and merely retain a standing dress for

about three weeks in June, ju st when they are laying; the body is then blackish brown, every feather broadly

edged with yellow, brown, and white, giving the bird a very light yellow-brown appearance ; breast much

lig h te r; belly never pure white as in the male, but, as well as the sides and breast, covered with black zigzag

lines 011 a rusty yellow and white ground. By the second week in June this dress is complete, but varies

so much in tint that scarcely any two birds are alike; all a t once they become much darker, and by the

beginning o f July the female has assumed a totally different and darker costume. About the end of the

month she is far more handsome than the male, her dress being brown-red variegated with blue-grey,

which often on the back appears in patches. But the females vary so much in colour that a minute

description of one would not apply to another. I .fancy both sexes retain this blue dress longer than any

other. I t gradually becomes lighter as the season advances, till a t length the old female is quite blue, but

always with some rusty mottled yellow feathers on the sid es; and about the middle o f October the blue dress

gives place to the pure white of winter.

“ The plumage of the young in the downy state is rusty yellow, with longitudinal markings and minute

spots o f black; the first dress after that is black mottled with rusty yellow and white above, underneath

pale rusty brown with blackish wavy lin es; wings greyish brown. Early in August the body-plumage

becomes greyish blue, finely streaked with black, and the pinions white instead of brown; this grey plumage

gradually becomes lighter, as in the old birds, till, like them, they assume their winter livery, and by the 1st

o f November there is no perceptible difference between old and young birds.

“ It appears, therefore, that the Swedish Ptarmigan has three distinct dresses in the course of the year,

and so many intermediate changes that they appear to have a different dress for every summer month.

“ The Ptarmigan may truly be said to be a child of the snow; for its real home is the higher fell tract,

and in the middle of summer on their very highest snow-clad summits. In the spring they come down to

the lower fells to breed, but you never find them there in the end o f summer. The pairing-season appears

to begin early in May, and to last a fortnight or three weeks. During this time the hoarse laughing love-call

o f the old male may be heard a t the earliest dawn on any of the fell-tops. This is soon answered by the

finer ‘ i-i-ack, i-i-ack ’ of the female, and the love-chase commences.

“ Both the Ptarmigan and the Willow-grouse are strictly monogamous. Some naturalists appear to have

an idea that both, when pairing, have a kind of “ lek ” or play, like the Capercaillie and Blackcock, both of

which are polygamous; I can only say, I never saw anything of the kind. The Ptarmigans certainly have

their favourite pairing-grounds on the fells, and here the birds assemble at daylight in the early spring, in

small but widely scattered flocks. The old males utter their peculiar love-call, which is answered by the

female, and they draw to g eth er; but, although there are several males in the neighbourhood, each one seems

to have his own particular stand and his own favourite female, and if by chance another male intrudes on

his ground, he drives it off.”

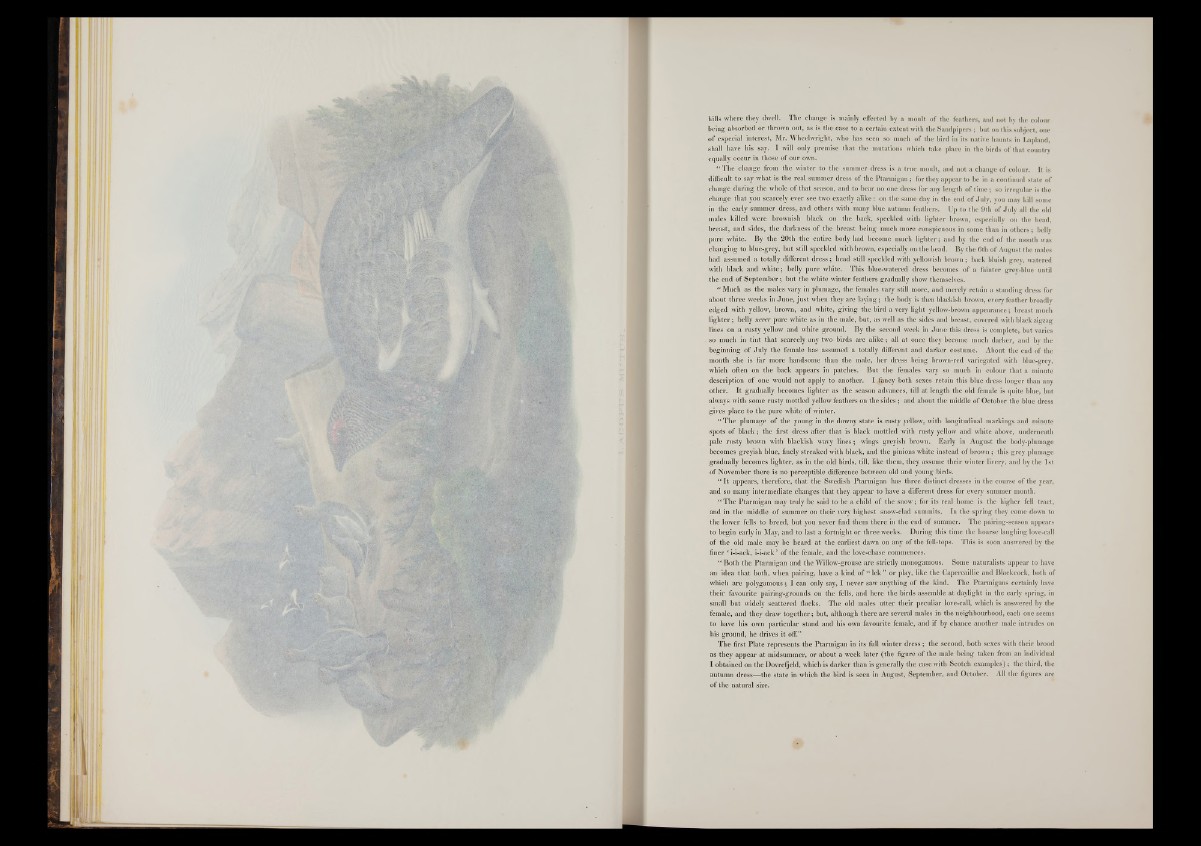

The first Plate represents the Ptarmigan in its full winter d res s ; the second, both sexes with their brood

as they appear a t midsummer, or about a week later (the figure of the male being taken from an individual

I obtained on the Dovrefjeld, which is darker than is generally the case with Scotch examples); the third, the

autumn dress—the state in which the bird is seen in August, September, and October. All the figures are

o f the natural size.