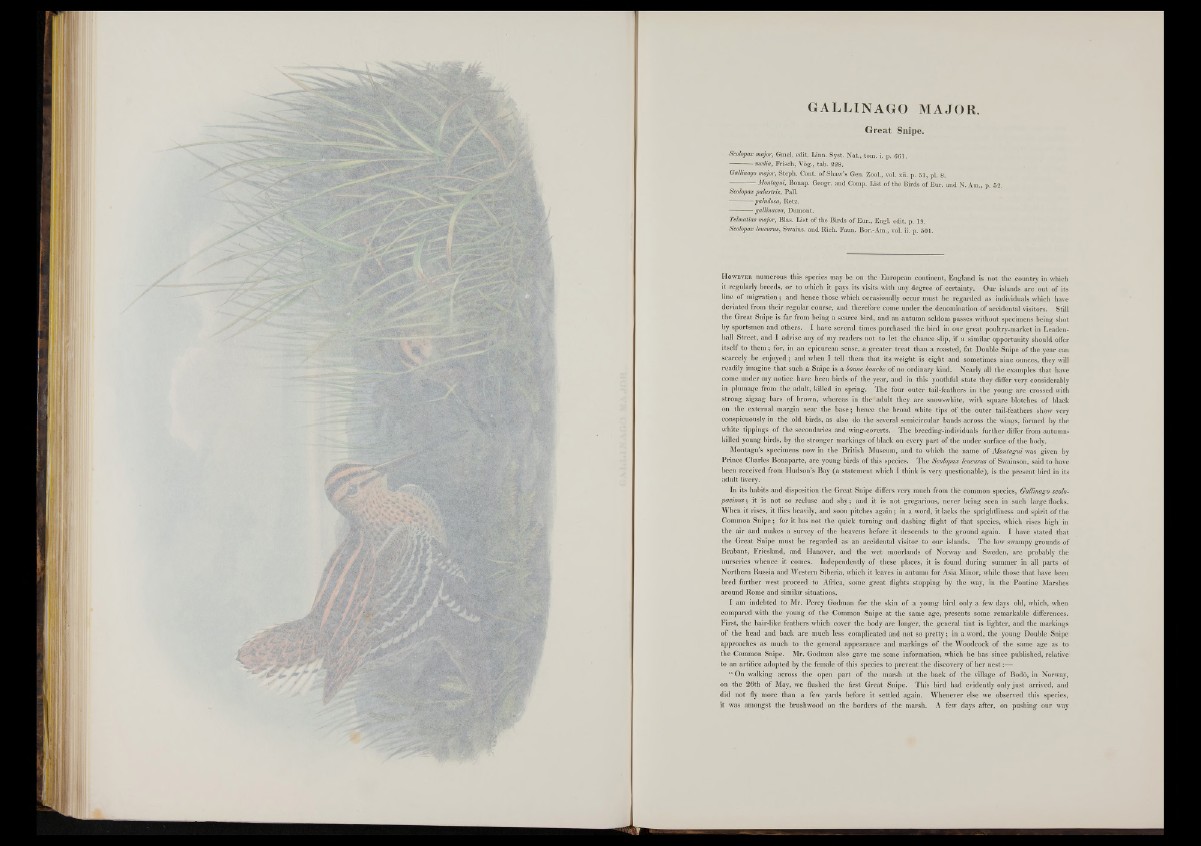

GALLINAGO MAJOR.

Great Snipe.

Scolopax major, Gmel. edit. Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 661.

— - — media, Frisch, Vog., tab. 228.

Gallinago major, Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xii. p. 51, pi. 8.

------------Montagui, Bonap. Geogr. and Comp. List of the Birds of Eur. and N. Am., p. 52.

Scolopax palustri*, Palll&p ■

-----------paludosa, Retz.

gallinacea, Dumont.

Telmatias major, Bias. List of the Birds of Eur., Engl. edit. p. 19.

Scolopax leucurus, Swains, and Rich. Faun. Bor.-Am., vol. ii. p. 501.

H ow ev e r numerous this species maybe, on the-European continent, England is not the country in which

it regularly breeds, or to which it pays its visits with any degree of certainty. Our islands are out of its

line o f migration; and hence those which occasionally occur must be regarded as individuals which have

deviated from their regular course, and therefore come under the denomination of accidental visitors. Still

the Great Snipe is far from being a scarce bird, and an autumn seldom passes without specimens being shot

by sportsmen and others. I have several times purchased the bird in our great poultry-market in Leaden-

liall Street, and I advise any o f my readers not to let the chance slip, if a similar opportunity should offer

itself to them ; for, in an epicurean sense, a greater treat than a roasted, fat Double Snipe o f the year can

scarcely be enjoyed; and when I tell them that its weight is eight and sometimes nine ounces, they will

readily imagine that such a Snipe is a bonne bouche o f no ordinary kind. Nearly all the examples that have

come under my notice have been birds o f the year, and in this youthful state they differ very considerably

in plumage from the adult, killed in spring. The four outer tail-feathers in the young are crossed with

strong zigzag bars o f brown, whereas in the adult they are snow-white, with square blotches of black

on the external margin near the base; hence the broad white tips of the outer tail-feathers show very

conspicuously in the old birds, as also do the several semicircular bands across the wings, formed by the

white tippings o f the secondaries and wing-coverts. The breeding-individuals further differ from autumn-

killed young birds, by the stronger markings of black on every part of the under surface of the body.

Montagu’s specimens now in the British Museum, and to which the name of Montagui was given by

Prince Charles Bonaparte, are young birds of this species. The Scolopax leucurus o f Swainson, said to have

been received from Hudson’s Bay (a statement which I think is very questionable), is the present bird in its

adult livery.

In its habits and disposition the Great Snipe differs very much from the common species, Gallinago scolo-

pacinus; it is not so recluse and sh y ; and it is not gregarious, never being seen in such large flocks.

When it rises, it flies heavily, and soon pitches ag a in ; in a word, it lacks the sprightliness and spirit o f the

Common Snipe; for it has not the quick turning and dashing flight of that species, which rises high in

the air and makes a survey of the heavens before it descends to the ground again. I have stated that

the Great Snipe must be regarded as an accidental visitor to our islands. The low swampy grounds of

Brabant, Friesland, and Hanover, and the wet moorlands o f Norway and Sweden, are probably the

nurseries whence it comes. Independently o f these places, it is found during summer in all parts of

Northern Russia and Western Siberia, which it leaves in autumn for Asia Minor, while those that have been

bred further west proceed to Africa, some great flights stopping by the way, in the Pontine Marshes

around Rome and similar situations.

I am indebted to Mr. Percy Godman for the skin of a young bird only a few days old, which, when

compared with the young of the Common Snipe a t the same age, presents some remarkable differences.

First, the hair-like feathers which cover the body are longer, the general tint is lighter, and the markings

of the head and back are much less complicated and not so pretty ; in a.word, the young Double Snipe

approaches as much to the general appearance and markings of the Woodcock of the same age as to

the Common Snipe. Mr. Godman also gave me some information, which he has since published, relative

to an artifice adopted by the female o f this species to prevent the discovery o f h er n e s t:—

“ O n walking across the open part o f the marsh at the back of the village o f Bodo, in Norway,

on the 26th o f May, we flushed the first Great Snipe. This bird had evidently only ju st arrived, and

did not fly more than a few yards before it settled again. Whenever else we observed this species,

it was amongst the brushwood on the borders o f the marsh. A few days after, on pushing our way