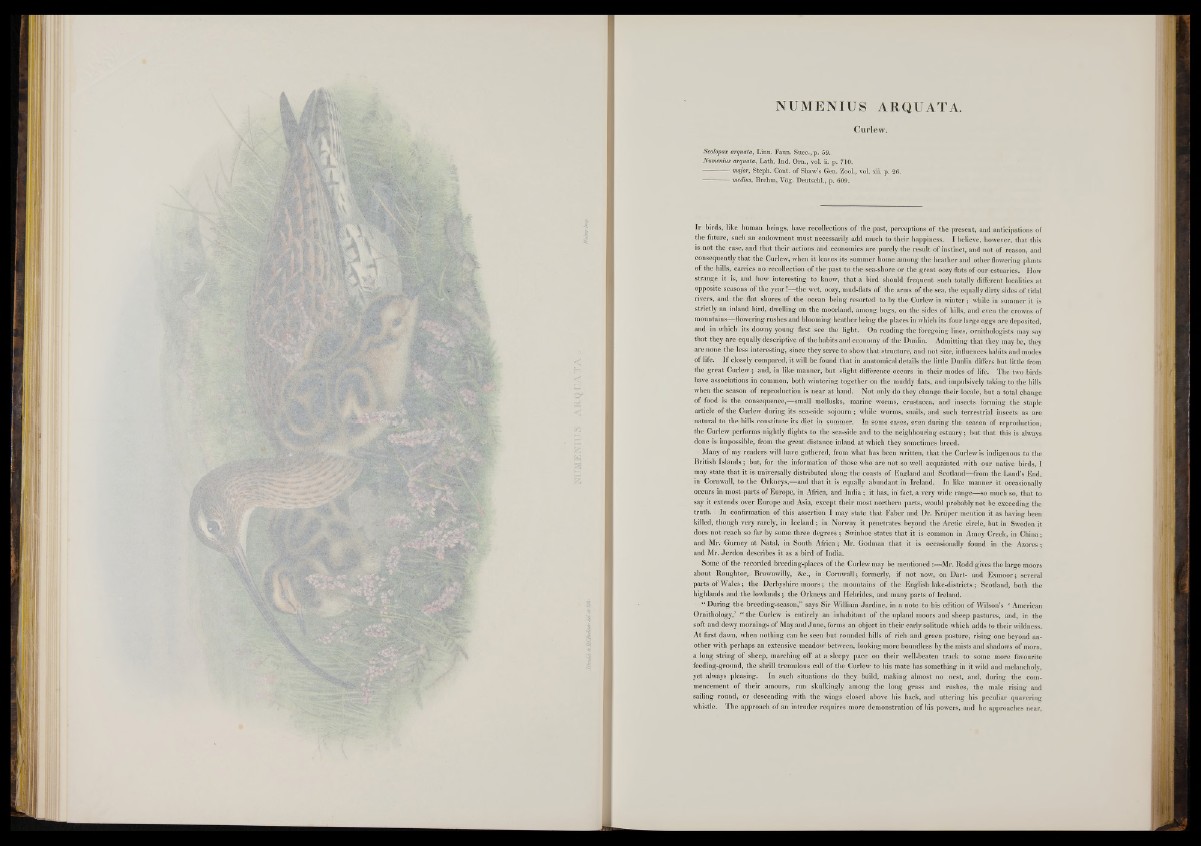

Curlew.

Scolopax arquata, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 59.

Numenim arquata, Lath. Ind. Ora., vol. ii. p. 710.

: major, Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xii. p. 26.

-------------medius, Brehm, Yog. Deutschl., p. 609.

If birds, like human beings, bave recollections o f the past, perceptions of the present, and anticipations of

the future, such an endowment must necessarily add much to their happiness. I believe, however, that this

is not the case, and that their actions and economies are purely the result of instinct, and not of reason, and

consequently that the Curlew, when it leaves its summer home among the heather and other flowering plants

o f the hills, carries no recollection o f the past to the sea-shore or the great oozy flats o f our estuaries. How

strange it is, and how interesting to know, that a bird should frequent such totally different localities at

opposite seasons o f the year !—the wet, oozy, mud-flats o f the arms of the sea, the equally dirty sides of tidal

rivers, and the flat shores of the ocean being resorted to by the Curlew in winter ; while in summer it is

strictly an inland bird, dwelling on the moorland, among bogs, on the sides of hills, and even the crowns of

mountains—flowering rushes and blooming heather being the places in which its four large eggs are deposited,

and in which its downy young first see the light. On reading the foregoing lines, ornithologists may say

that they are equally descriptive o f the habits and economy of the Dunlin. Admitting that they may be, they

are none the less interesting, since they serve to show that structure, and not size, influences habits and modes

o f life. If closely compared, it will be found that in anatomical details the little Dunlin differs but little from

the great Curlew ; and, in like manner, but slight difference occurs in their modes o f life. The two birds

have associations in common, both wintering together on the muddy flats, and impulsively taking to the hills

when the season o f reproduction is near at hand. Not only do they change their locale, but a total change

o f food is the consequence,—small mollusks, marine worms, Crustacea, and insects forming the staple

article of the Curlew during its sea-side sojourn ; while worms, snails, and such terrestrial insects as are

natural to the hills constitute its diet in summer. In some cases, even during the season of reproduction,

the Curlew performs nightly flights to the sea-side and to the neighbouring estuary ; but that this is always

done is impossible, from the great distance inland a t which they sometimes breed.

Many o f my readers willdfave gathered, from what has been written, that the Curlew is indigenous to the

British Islands ; but, for the information o f those who are not so well acquainted with our native birds, I

may state that it is universally distributed along the coasts of England and Scotland—from the Land’s End,

in Cornwall, to the Orkneys,—and that it is equally abundant in Ireland. In like manner it occasionally

occurs in most parts o f Europe, in Africa, and India ; it has, in'fact, a very wide range—so much so, that to

say it extends over Europe and Asia, except their most northern parts, would probably not be exceeding the

truth. In confirmation of this assertion I may state th at Faber and Dr. Kriiper mention it as having been

killed, though very rarely, in Iceland ; in Norway it penetrates beyond the Arctic circle, but in Sweden it

does not reach so far by some three degrees ; Swinhoe states th at it is common in Amoy Creek, in China;

and Mr. Gurney a t Natal, in South Africa ; Mr. Godman th at it is occasionally found in the Azores ;

and Mr. Jerdon describes it as a bird o f India.

Some o f the recorded breeding-places of the Curlew may be mentioned :—Mr. Rodd gives the large moors

about Roughtor, Brownwilly, &c., in Cornwall; formerly, if not now, on Dart- and Exmoor; several

parts o f Wales ; the Derbyshire moors ; the mountains of the English lake-districts ; Scotland, both the

highlands and the lowlands ; the Orkneys and Hebrides, and many parts o f Ireland.

“ During the breeding-season,” says Sir William Jardine, in a note to his edition o f Wilson’s ‘ American

Ornithology,’ “ the Curlew is entirely an inhabitant o f the upland moors and sheep pastures, and, in the

soft and dewy mornings o f May and June, forms an object in their early solitude which adds to their wildness.

At first dawn, when nothing can be seen but rounded hills of rich and green pasture, rising one beyond another

with perhaps an extensive meadow between, looking more boundless by the mists and shadows of morn,

a long string of sheep, marching off a t a sleepy pace on their well-beaten track to some more favourite

feeding-ground, the shrill tremulous call of tbe Curlew to his mate has something in it wild and melancholy,

yet always pleasing. In such situations do they build, making almost no nest, and, during the commencement

of their amours, run skulkingly among the long grass and rushes, the male rising and

sailing round, or descending with the wings closed above his back, and uttering his peculiar quavering

whistle. The approach of an intruder requires more demonstration of his powers, and he approaches near,