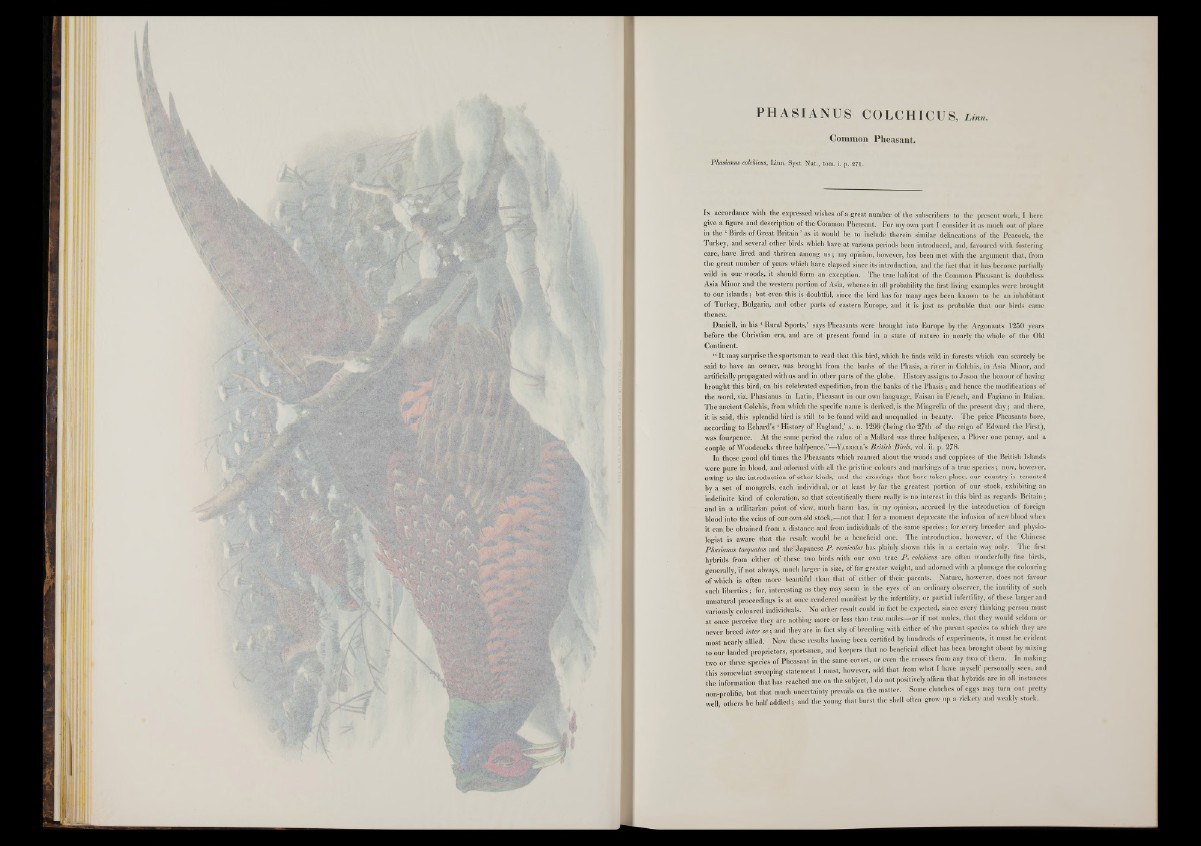

PHASIANUS COLCHICUS, Linn.

Common Pheasant.

Phasianus colchicus, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 271.

In accordance with the expressed wishes of a great number of the subscribers to the present work, I here

give a figure and description of the Common Pheasant. For my own part I consider it as much out of place

in the ‘Birds of Great Britain ’ as it would be to include therein similar delineations of the Peacock, the

Turkey, and several other birds which have at various periods been introduced, and, favoured with fostering

care, have lived and thriven among u s; my opinion, however, has been met with the argument that, from

the great number of years which have elapsed since its introduction, and the fact that it has become partially

wild in our woods, it should form an exception. The true habitat of the Common Pheasant is doubtless

Asia Minor and the western portion of Asia, whence in all probability the first living examples were brought

to our islands; but even this is doubtful, since the bird has for many ages been known to be an inhabitant

of Turkey, Bulgaria, and other parts of eastern Europe, and it is just as probable that our birds came

thence.

Daniell, in his ‘ Rural Sports/ says Pheasants were brought into Europe by the Argonauts 1250 years

before the Christian era, and are at present found in a state of nature in nearly the whole of the Old

Continent.

“ I t may surprise the sportsman to read that this bird, which he finds wild in forests which can scarcely be

said to have an owner, was brought from the banks of the Phasis, a river in Colchis, in Asia Minor, and

artificially propagated with us and in other parts of the globe. History assigns to Jason the honour o f having

brought this bird, on. his celebrated expedition, from the banks of the Phasis; and hence the modifications of

the word, viz. Phasianus in Latin, Pheasant in our own language, Faisan in French, and Fagiano in Italian.

T he ancient Colchis, from which the specific name is derived, is the Mingrelia of the present day; and there,

it is said, this splendid bird is still ;to be found wild and unequalled in beauty. The price Pheasants bore,

according to Echard’s ‘ History of England,’ a . d . 1299 (being the 27th of the reign of Edward the First),

was fourpence. At the same period the value of a Mallard was three halfpence, a Plover one penny, and a

couple o f Woodcocks three halfpence/teYARRELi/s British Birds, vol. ii. p. 278.

In those good old times the Pheasants which roamed about the woods and coppices of the British Islands

were pure in blood, and adorned with all the pristine colours and markings o f a true species; now, however,

owing to the introduction of other kinds, and the crossings that have taken place, our country is tenanted

by a set of mongrels, each individual, or at least by far the greatest portion of our stock, exhibiting an

indefinite kind o f coloration, so that scientifically there really is no interest in this bird as regards Britain ;

and in a utilitarian point of view, much harm has, in my opinion, accrued by the introduction of foreign

blood into the veins o f our own old stock,—not that I for a moment deprecate the infusion o f new blood when

it can be obtained from a distance and from individuals of the same species; for every breeder and physiologist

is aware that the result would be a beneficial one. The introduction, however, of the Chinese

Phasianus torqmtus and the Japanese P. versicolor has plainly shown this in a certain way only. The first

hybrids from either of these two birds with our own true P . colchicus are often wonderfully fine birds,

generally, if not always, much larger in size, of far greater weight, and adorned with a plumage the colouring

of which is often more beautiful than that of either of their parents. Nature, however, does not favour

such liberties ; for, interesting as they may seem in the eyes of an ordinary observer, the inutility o f such

unnatural proceedings is at once rendered manifest by the infertility, or partial infertility, of these larger and

variously coloured individual!! No other result could in fact be expected, since every thinking person must

a t once perceive they are nothing more or less than true mules-^or if not mules, that they would seldom or

never breed inter s e ; and they are in fact shy of breeding with either of the parent species to which they are

most nearly allied. Now these results having been certified by hundreds of experiments, it must be evident

to our landed proprietors, sportsmen, and keepers that no beneficial effect has been brought about by mixing

two or three species o f Pheasant in the same covert, or even the crosses from any two of them. In making

this somewhat sweeping statement I must, however, add that from what I have myself personally seen, and

the information that has reached me on the subject, I do not positively affirm that hybrids are in all instances

non-prolific, but that much uncertainty prevails on the matter. Some clutches of eggs may turn out pretty

well, others be half addled; and the young that burst the shell often grow up a rickety and weakly stock.