HI.

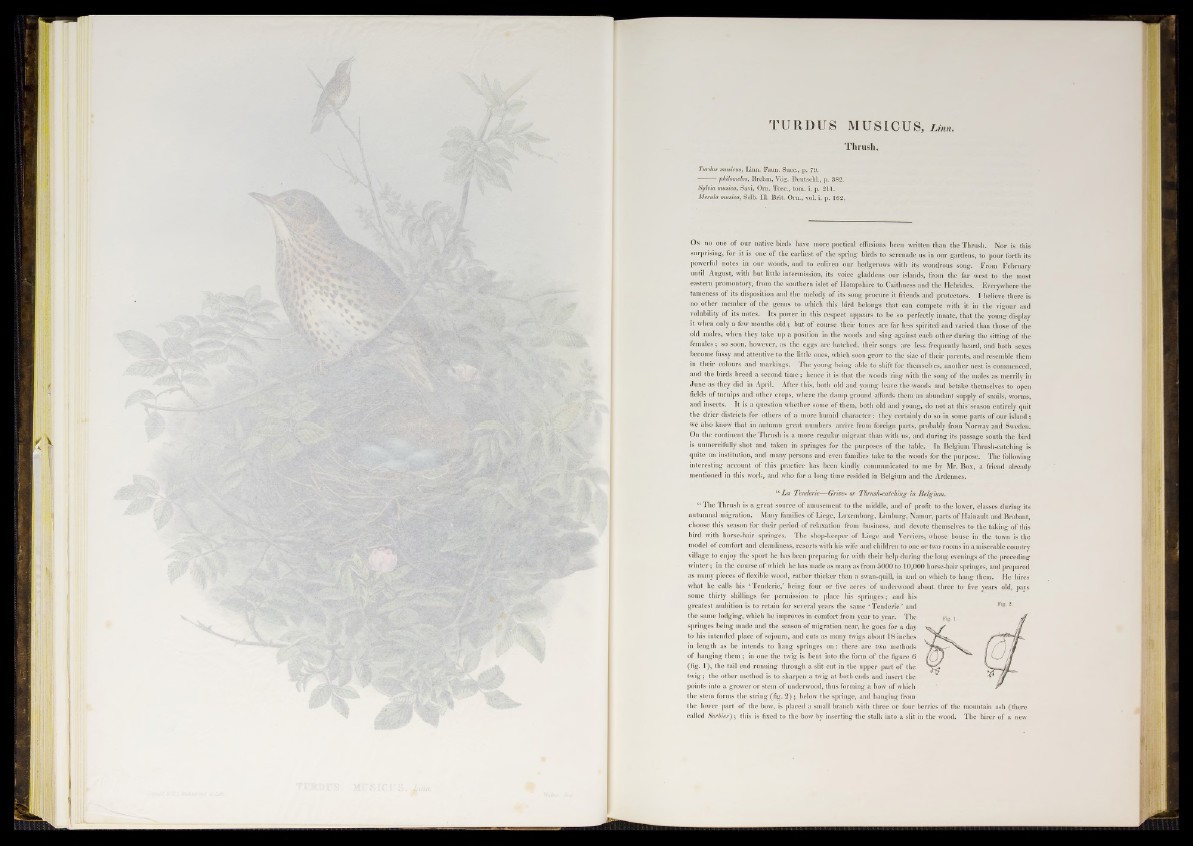

TU R D US MUSICUS, Linn.

Thrush.

Turdus musicus, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 79.

philomelos, Brehm, Vog. Deutschl., p. 382.

Sylvia musica, Savi, Orn. Tosc., tom. i. p. 211.

Merula musica, Selb. 111. Brit. Orn., vol. i. p. 162.

On no one of our native birds have more poetical effusions been written than the Thrush. Nor is this

surprising, for it is one o f the earliest of the spring birds to serenade us in our gardens, to pour forth its

powerful notes in our woods, and to enliven our hedgerows with its wondrous song. From February

until August, with but little intermission, its voice gladdens our islands, from the far west to the most

eastern promontory, from the southern islet of Hampshire to Caithness and the Hebrides. Everywhere the

tameness of its disposition and the melody of its song procure it friends and protectors. I believe there is

ho other member o f the genus to which this bird belongs that can compete with it in the vigour and

volubility o f its notes. Its power in this respect appears to be so perfectly innate, that the young display

it when only a few months o ld ; but of course their tones are far less spirited and varied than those o f the

old males, when they take up a position in the woods and sing against each other during the sitting o f the

females; so soon, however, as the eggs are hatched, their songs are less frequently heard, and both sexes

become fussy and attentive to the little ones, which soon grow to the size of their parents, and resemble them

in their colours and markings. The young being able to shift for themselves, another nest is commenced,

and the birds breed a second time; hence it is that the woods ring with the song of the males as merrily in

Ju n e as they did in April. • After this, both old and young leave the -woods and betake themselves to open

fields of turnips and other crops, where the damp ground affords them an abundant supply of snails, worms,

and insects. It is a question whether some of them, both old and young, do not a t this season entirely quit

the drier districts for others of a more humid character: they certainly do so in some parts of our island;

we also know that in autumn great numbers arrive from foreign parts, probably from Norway and Sweden.

On the continent the Thrush is a more regular migrant than with us, and during its passage south the bird

is unmercifully shot and taken in springes for the purposes of the table. In Belgium Thrush-catching is

quite an institution, and many persons and even families take to the woods for the purpose. The following

interesting account o f this practice has been kindly communicated to me by Mr. Box, a friend already

mentioned in this work, and who for a long time resided in Belgium and the Ardennes.

“ L a Tenderie— Grive- or Thrush-catching in Belgium.

“ The Thrush is a great source of amusement to the middle, and of profit to the lower, classes during its

autumnal migration. Many families of Liege, Luxemburg, Limburg, Namur, parts of Hainault and Brabant,

choose this season for their period of relaxation from business, and devote themselves to the taking o f this

bird with horse-hair- springes. The shop-keeper o f Liege and Verviers, whose house in the town is the

model o f comfort and cleanliness, resorts with his wife and children to one o r two rooms in a miserable country

village to enjoy the sport he has been preparing for with their help during the long evenings of the preceding

win ter; in the course o f which he has made as many as from 5000 to 10,000 horse-hair springes, and prepared

as many pieces o f flexible wood, rather thicker than a swan-quill, in and on which to hang them. He hires

what he calls his ‘ Tenderie,’ being four or five acres of underwood about, three to five years old, pays

some thirty shillings for permission to place his springes; and his

greatest ambition is to retain for several years the same ‘ Tenderie ’ and

the same lodging, which he improves in comfort from year to year. The

springes being made and the season of migration near, he goes for a day

to his intended place of sojourn, and cuts as many twigs about 18 inches

in length as he intends to hang springes o n : there are two methods

o f hanging th em ; in one the twig is bent into the form of the figure 6

(fig. 1) , the tail end running through a slit cut in the upper part o f the

twig ; the other method is to sharpen a twig at both ends and insert the

points into a grower or stem o f underwood, thus forming a bow o f which

the stem forms the string (fig. 2) ; below the springe, and hanging from

the lower part o f the bow, is placed a small branch with three or four berries o f the mountain ash (there

called Sorbier') ; this is fixed to the bow by inserting the stalk into a slit in the wood. The hirer of a new