Walter I Cohn, J n y

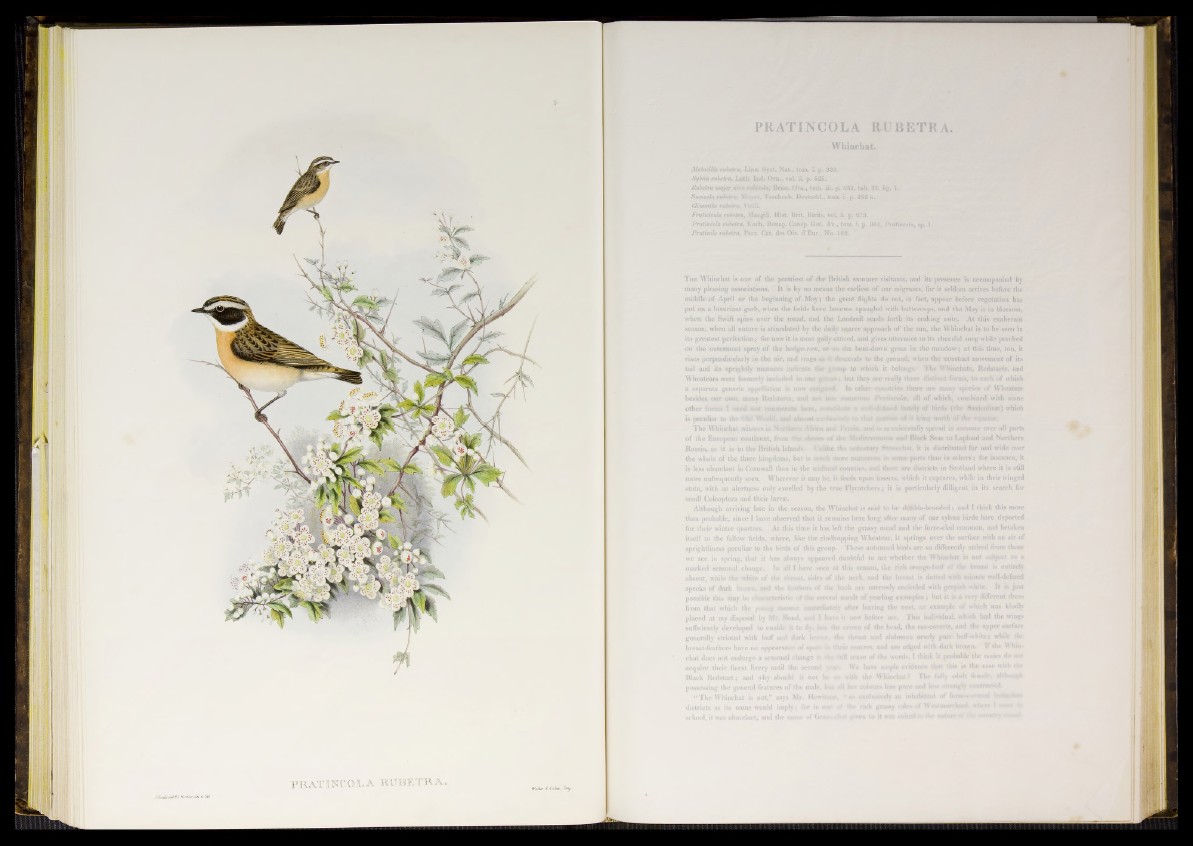

P R A T I N C O L A R U B E T R A .

PRATINCOLA RÜBETR

Whinchat.

Motacilla rubeira, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 332.

Sylvia rubeira, Lath. Ind. Orn., vol. ii. p. 525.

Rubeira major srve rubicola, Briss. Orn,, tom. iii. p. 4 3 2 , tab; 24. fig. 1.

Saxícola rubeira, Moyer, Taschenb. Deutschl., tom. i . p. 2 5 2 b .

(Enanthe rubeira, Vieill.

Fruticicola rubeira, Macgill. Hist. Brit. Birds, vol. ii. p. 273.

Pratíncola rubeira, Koch, Bonap. Consp. Gen. Av., tom. i. p. 304, Prat\

Praticola rubeira, Parz. Cat. des Ois. d’Eur., No. 162.

T h e Whinchat is one of the prettiest o f the British summer visitants, and its presence is accompanied by

many pleasing associations. It is by no means the earliest of our migrants, for it seldom arrives before the

middle o f April o r the beginning of- May; the great flights do not, in fact, appear before vegetation has

put on a luxuriant garb, when the fields have become spangled with buttercups, and the May is in blossom,

when the Swift spins over the mead, and the Landrail sends forth its craking note. At this exuberant

season, when all nature is stimulated by the daily nearer approach of the sun, the Whinchat is to be seen in

its greatest perfection; for. now it is most gaily attired, and gives ntterance to its cheerful song while perched

on the outermost spray of the hedge-row, or on the bent-down grass in the meadow; at this time, too, it

rises perpendicularly in the air, and sings as « descends to the ground, when the constant movement o f its

tail and its sprightly manners indicate the group to which it belongs. The Whinchats, Redstarts, and

Wlieatears were formerly included m one h h c h but they are really three distinct forms, to each o f which

a separate generic appellation is now assigned. In other countries there are many species o f Wheatear

besides our own. many Redstarts, ami not tests numeri*»* i^ratineolce, all o f which, combined with some

other forma I need not enumerate here, txmel&seb* n ovfMe&Mtd family o f birds (the Saxicolitue) which

is peculiar to the OW World, ¡mm) ahnoat «setasivwty to that pew©®» o f it lying north o f the etpiator.

The Whinchat winters in Nurtbern Africa and Persia, and is as universally spread in summer over all parts

of the European continent, from the shares o f the Mediterranean and Black Seas to Lapland and Northern

Russia, as it is in the B ritish Islands. Unlike the aedentary Stonechat, it is distributed far and wide over

the whole o f the three kingdoms, but is much more numerous in some parts than in others ; for instance, it

is less abundant in Cornwall than in the midland counties, and there are districts in Scotland where it is still

more unfrequently seen. Wherever it may be, it feeds upon insects, which it captures, while in their winged

state, with an alertness only excelled by the true Flycatchers; it is particularly dilligent in its search for

small Coleoptera and their larvae.

Although arriving late in the season, the Whinchat is said to be double-brooded; and I think this more

than probable, since I uave observed that it remains here long after many of our sylvan birds have departed

for their winter quarters. At this time it has left the grassy mead and the furze-clad common, and betaken

itself to the fallow fields, where, like the clodbopping Wheatear, it springs over the surface with an air of

sprightliuess peculiar to the birds of this group. These autumnal birds are so differently attired from those

we see in spring, that it has always appeared doubtful to me whether the Whinchat is not subject to a

marked seasonal change. In all I have seen at this season, the rich owuige*bnff of the breast is entirely

absent, while the white of the throat, sides of the neck, and the breast is dotted with minute well-defined

specks of dark brown, and the feathers of the hack are narrowly encircled with greyish white. It is just

possible this may be characteristic < {'the second moult of yearling examples ; but it is. a very different dress

from that which the young assume immediately after leaving the nest, i.n example of which was kindly

placed at my disposal by Mr. Bond, and 1 have it now before me. This individual, which had the wings

sufficiently developed to enahk it to fly, bra the crown of the head, the ear-covert«, and the upper surface

generally striated with buff and dark brown, the throat and abdomen nearly pure buff-white; while the

hreast-feathers have no appearance o f spots m their centres, and are edged with dark brojyn. I f the W bio-

chat does not undergo a seasonal change in the full sense of the words, I think it probable the males do not

acquire their finest livery until the second jw

Black Redstart; and why should it not he w* with the Whinchat? The futty adult female, although

possessing the general features o f the male, bus a# her colours less pure and le » strongly rontraated

“ The Whinchat is not,” says Mr. Hewitoew. - so exclusively an inhabitant of furwseuvered bw

districts as its name would imply; for in one of the rich grassy vales o f vV rxtmoremM. whew

school, it was abundant, and the name of Gram-chut given to it was sotted to tit«- oat»ur *«