PRATINCOLA RUBETRA.

Whinchat.

Motacilla rubetra, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 332.

Sylvia rubeira, Lath. Ind. Orn., vol. ii. p. 525.

Rubetra major sive rubicola, Briss. Orn., tom. iii. p. 432, tab. 24. fig. 1 .

Saxícola rubetra, Meyer, Taschenb. Deutschl., tom. i. p. 252 b .

(Iin an the rubetra, Vieill.

Fruticicola rubetra, Macgill. Hist. Brit. Birds, vol. ii. p. 273.

Pratíncola rubetra, Koch, Bonap. Consp. Gen. Av., tom. i. p. 304, Pratíncola, sp. 1.

Praticola rubetra, Parz. Cat. des Ois. d’Eur., No. 162.

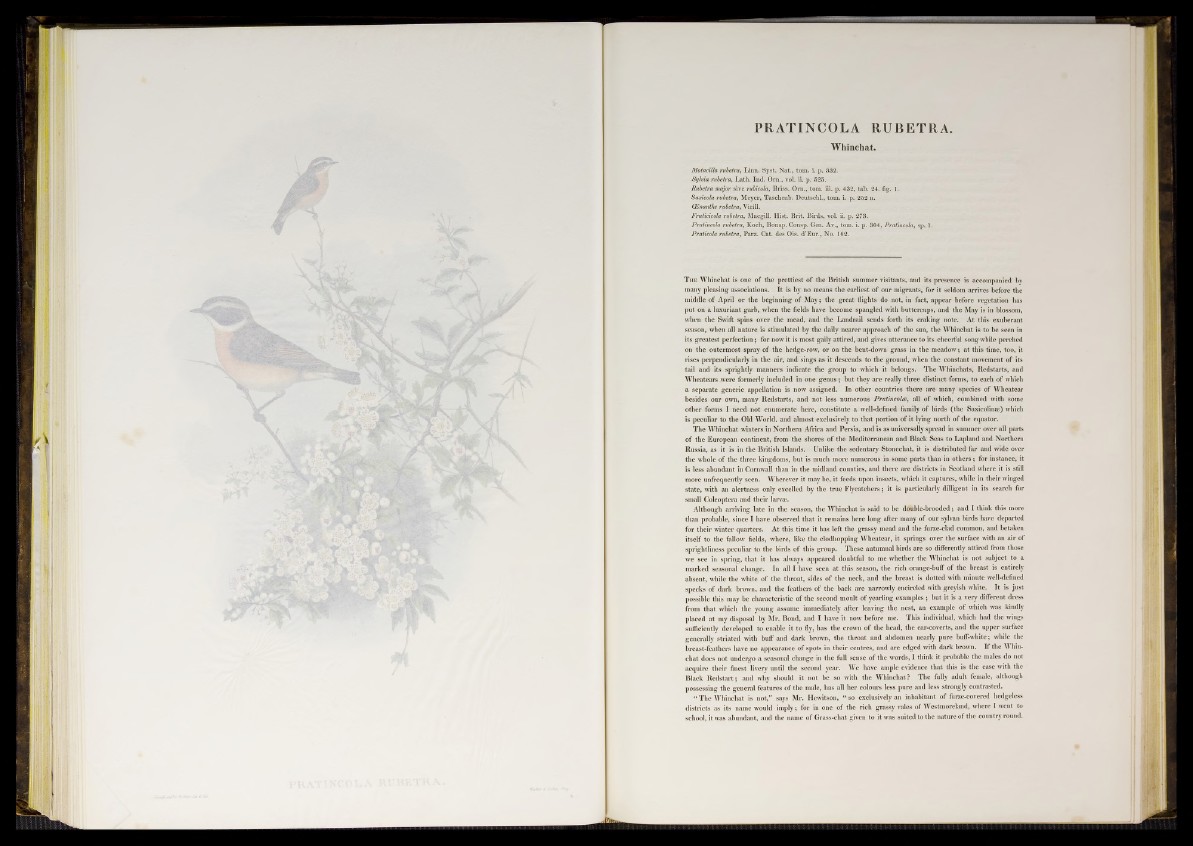

T h e Whinchat is one of the prettiest of the British summer visitants, and its presence is accompanied by

many pleasing associations. I t is by no means the earliest of our migrants, for it seldom arrives before the

middle of April or the beginning o f May ; the great flights do not, in fact, appear before vegetation has

put on a luxuriant garb, when the fields have become spangled with buttercups, and the May is in blossom,

when the Swift spins over the mead, and the Landrail sends forth its craking note. At this exuberant

season, when all nature is stimulated by the daily nearer approach of the sun, the Whinchat is to be seen in

its greatest perfection ; for now it is most gaily attired, and gives utterance to its cheerful song while perched

on the outermost spray of the hedge-row, or on the bent-down grass in the meadow ; at this time, too, it

rises perpendicularly in the air, and sings as it descends to the ground, when the constant movement of its

tail and its sprightly manners indicate the group to which it belongs. The Whinehats, Redstarts, and

Wheatears were formerly included in one genus ; but they are really three distinct forms, to each o f which

a separate generic appellation is now assigned. In other countries there are many species of Wheatear

besides our own, many Redstarts, and not less numerous Pratincoles, all o f which, combined with some

other forms I need not enumerate here, constitute a well-defined family o f birds (the Saxieolinæ) which

is peculiar to the Old World, and almost exclusively to that portion of it lying north of the equator.

The Whinchat winters in Northern Africa and Persia, and is as universally spread in summer over all parts

of the European continent, from the shores of the Mediterranean and Black Seas to Lapland and Northern

Russia, as it is in the British Islands. Unlike the sedentary Stonechat, it is distributed far and wide over

the whole of the three kingdoms, but is much more numerous in some parts than in others ; for instance, it

is less abundant in Cornwall than in the midland counties, and there are districts in Scotland where it is still

more unfrequently seen. Wherever it may be, it feeds upon insects, which it captures, while in their winged

state, with an alertness only excelled by the true Flycatchers ; it is particularly dilligent in its search for

small Coleoptera and their larvæ.

Although arriving late in the season, the Whinchat is said to be double-brooded ; and I think this more

than probable, since I have observed that it remains here long after many of our sylvan birds have departed

for their winter quarters. At this time it has left the grassy mead and the furze-clad common, and betaken

itself to the fallow fields, where, like the clodhopping Wheatear, it springs over the surface with an air of

sprightliness peculiar to the birds of this group. These autumnal birds are so differently attired from those

we see in spring, that it has always appeared doubtful to me whether the Whinchat is not subject to a

marked seasonal change. In all I have seen a t this season, the rich orange-buff of the breast is entirely

absent, while the white of the throat, sides of the neck, and the breast is dotted with minute well-defined

specks of dark brown, and the feathers o f the back are narrowly encircled with greyish white. It is just

possible this may be characteristic of the second moult of yearling examples ; but it is a very different dress

from that which the young assume immediately after leaving the nest, an example of which was kindly

placed at my disposal by Mr. Bond, and I have it now before me. This individual, which had the wings

sufficiently developed to enable it to fly, has the crown o f the head, the ear-coverts, and the upper surface

generally striated with buff and dark brown, the throat and abdomen nearly pure buff-white; while the

breast-feathers have no appearance of spots in their centres, and are edged with dark brown. If the Whin-

chat does not undergo a seasonal change in the full sense of the words, I think it probable the males do not

acquire their finest livery until the second year. We have ample evidence that this is the case with the

Black Redstart; and why should it not be so with the Whinchat? The fully adult female, although

possessing the general features of the male, has all her colours less pure and less strongly contrasted.

“ The Whinchat is not,” says Mr. Hewitson, “ so exclusively an inhabitant of furze-covered hedgeless

districts as its name would imply ; for in one of the rich grassy vales of Westmoreland, where I went to

school, it was abundant, and the name of Grass-chat given to it was suited to the nature of the country round.

5 'K im A - C O I I T T i i i I. I I '.