Nightingale.

Motacilla luscinia, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 88.

Sylvia luscinia, Lath. Ind. Ora., vol. ii. p. 506.

Curruca luscinia, Koch, Baier. Zool., tom. i. p. 154.

Philomela luscinia, Selb. 111. Brit. Orn., vol. i. p. 206.

Luscinia philomela, Bonap. Geog. and Comp. List of Birds of Eur. and N. Amer., p. 15.

Lusciola luscinia, Keys. & Bias. Wirbelth. Eur., p. 58.

At certain periods of the year the Nightingale may be found in North Africa, Palestine, Asia Minor, and

Persia, but not in India or the Himalayas as has been stated. On the continent of Europe it is a summer

visitant to Spain, Italy, Greece, Bulgaria, the Crimea, France, Switzerland, Germany, Southern Russia, and

Sweden. Of the British Islands its visits are principally confined to England, and are even restricted

to particular portions of the country. Thus it is never found in Cornwall, seldom in Devonshire, and

scarcely ever to the northward of Yorkshire or Lancashire; its favourite counties are Kent, Middlesex,

Sussex, and Surrey, while those of Wilts, Berks, Bucks, and Essex are but little less resorted to by it. Its

immigration to this country is for the purpose of reproduction.

“ It is a commonly received opinion,” says Mr. Edward Romilly in a note to me, “ that there are no

Nightingales in Wales. An exception should, however, be made for a district of Glamorganshire, lying on

the Bristol Channel, between Cardiff and Fonmore Castle, which is about eight miles (as the crow flies) west

of Cardiff. Nightingales abound in the woods of Wenvoe Castle, Porthkerry, and, I believe, Court yr ala,

àud are heard there every spring. Whether they are found north of the Cardiff and Cowbridge Road I am

unable to ascertain. In the spring of 1855 a male, which had been shot at Porthkerry, was sent to Mr.

Yarrell by Captain Boteler o f Llandough Castle ; and another, shot the same year, is in my possession. In the

very cold spring of the present year (1859) Nightingales were heard singing on each side of my house at

Porthkerry, and in many other places in the neighbouring woods ; and they are constant visitors there every

year.”

In England the Nightingale is associated with the violet, the cowslip, the daffodil, and a few more

o f those charming gifts of Flora which bedeck the children’s May-Day garlands at the joyous season of spring,

.—the bird and the flowers being held in remembrance through life, whether its span be a short or a long

one, or whether it be passed in a crowded city or a country village.

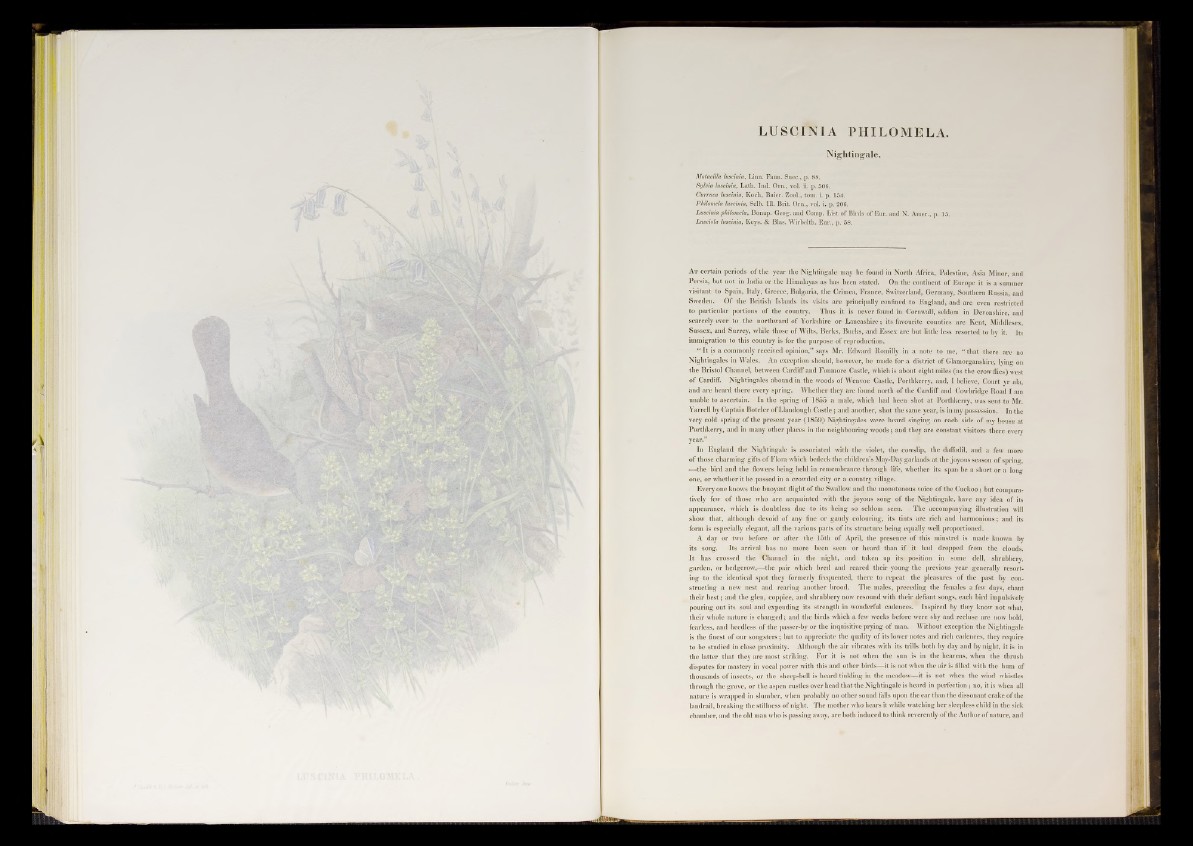

Everyone knows the buoyant flight of the Swallow and the monotonous voice o f the Cuckoo; but comparatively

few o f those who are acquainted with the joyous song of the Nightingale, have any idea of its

appearance, which is doubtless due to its being so seldom seen. The accompanying illustration will

show that, although devoid of any fine or gaudy colouring, its tints are rich and harmonious; and its

form is especially elegant, all the various parts of its structure being equally well proportioned.

A day or two before or after the 15th of April, the presence of this minstrel is made known by

its song. Its arrival has no more been seen or heard than if it had dropped from the clouds.

I t has crossed the 'Channel in the night, and taken up its. position in some dell, shrubbery,

garden, or hedgerow,—the pair which bred and reared their young the previous year generally resorting

to the identical spot they formerly frequented, there to repeat the pleasures of the past by constructing

a new nest and rearing another brood. The males, preceding the females a few days, chant

their best ; and the glen, coppice, and shrubbery now resound with their defiant songs, each bird impulsively

pouring out its soul and expending its strength in wonderful cadences. ' Inspired by they know not what,

their whole nature is changed'; and the birds which a few weeks before were shy and recluse are now bold,

fearless, and heedless of the passer-by or the inquisitive prying of man. Without exception the Nightingale

is the finest of our songsters ; but to appreciate the quality of its lower notes and rich cadences, they require

to be studied in close proximity. Although the air vibrates with its trills both by day and by night, it is in

the latter that they are most striking. For it is not when the sun is in the heavens, when thé thrush

disputes for mastery in vocal power with this and other birds—it is not when the air is filled with the hum of

thousands of insects, or the sheep-bell is heard tinkling in the meadow—it is not when the wind whistles

through the grove, or the aspen rustles over head that the Nightingale is heard in perfection ; no, it is when all

nature is wrapped in slumber, when probably no other sound falls upon the ear than the dissonant crake of the

landrail, breaking the stillness of night. The mother who hears it while watching her sleepless child in the sick

chamber, and the old man who is passing away, are both induced to think reverently o f the Author of nature, and