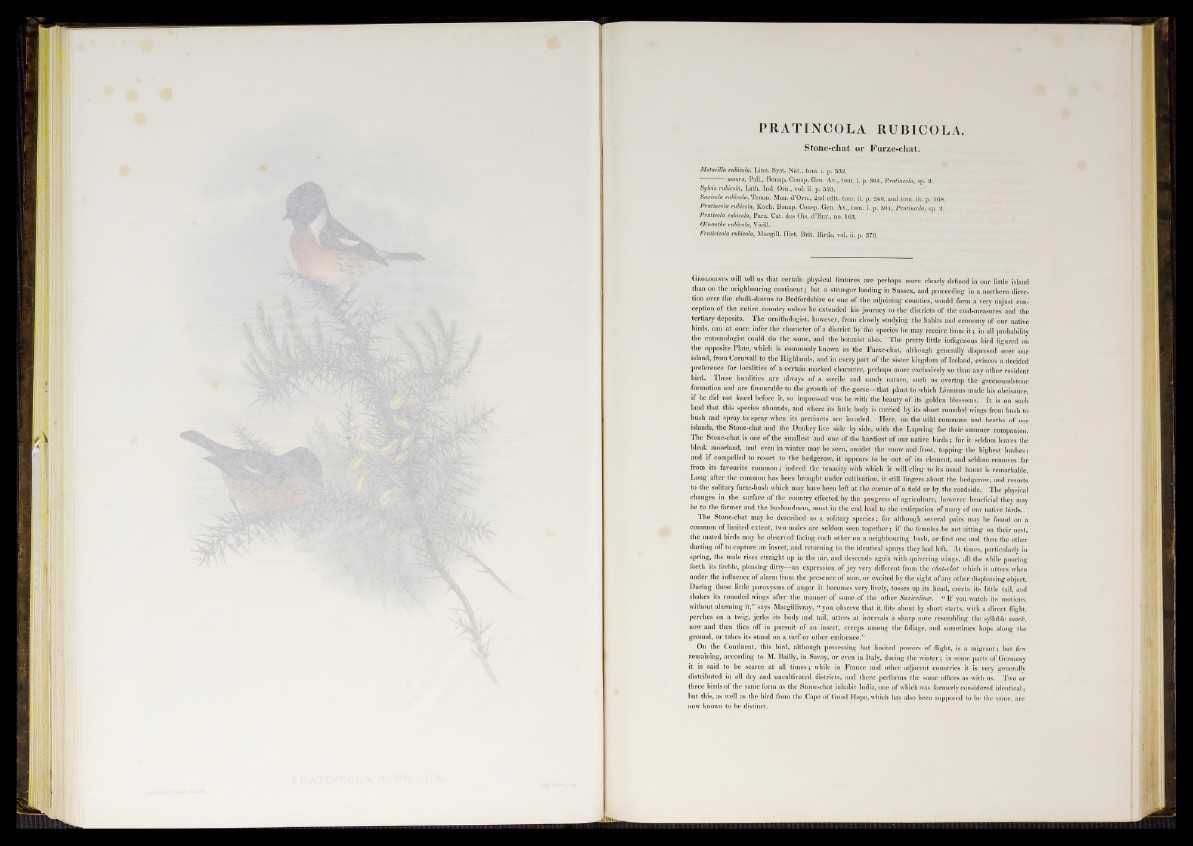

PRATINCOLA RUBICOLA.

Stone-chat or Furze-chat.

Motacilla ridicola, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 332.

-----------maura, Pall., Bonap. Consp. Gen. Av., tom. i. p. 304, Pratíncola, sp. 2.

Sylvia rubicola, Láth. Ind. Ora., vol. ii. p. 523.

Saxícola rubicola, Temm. Man. d’Orn., 2nd edit. tom. ii. p. 246, and tom. iii. p. 168.

Pratíncola rubicola, Koch, Bonap. Consp. Gen. Av., tom. i. p. 304, Pratíncola, sp. 2.

Praticola rubicola, Parz. Cat. des Ois. d’Eur., no. 163.

(Enanthe rubicola, Vieill.

Fruticicola rubicola, Macgill. Hist. Brit. Birds, vol. ii. p. 279.

G eo lo g ist s will tell us that certain physical features are perhaps more clearly defined in our little island

than on the neighbouring continent; but a stranger landing in Sussex, and proceeding in a northern direction

over the chalk-downs to Bedfordshire or one o f the adjoining counties, would form a very unjust conception

of the entire country unless he extended his journey to the districts o f the coal-measures and the

tertiary deposits. The ornithologist, however, from closely studying the habits and economy of our native

birds, can at once infer the character of a district by the species he may receive from i t ; in all probability

the entomologist could do the same, and the botanist also. The pretty little indigenous bird figured on

the opposite Plate, which is commonly known as the Furze-chat, although generally dispersed over our

island, from Cornwall to the Highlands, and in every part of the sister kingdom of Ireland, evinces a decided

preference for localities of a certain marked character, perhaps more exclusively so than any other resident

bird. These localities are always of a sterile and sandy nature, such as overtop the greensandstone

formation and are favourable to the growth o f the gorse—that plant to which Linnaeus made his obeisance,

if he did not kneel before it, so impressed was he with the beauty o f its golden blossoms. I t is on such

land that this species abounds, and where its little body is carried by its short rounded wings from bush to

bush and spray to spray when its precincts are invaded. Here, on the wild commons and heaths of our

islands, the Stone-chat and the Donkey live side by side, with the Lapwing for their summer companion.

The Stone-chat is one of the smallest and one of the hardiest of our native b ird s; for it seldom leaves the

bleak moorland, and even in winter may be seen, amidst the snow and frost, topping the highest bushes;

and if compelled to resort to the hedgerow, it appears to be out of its element, and seldom removes far

from its favourite common; indeed the tenacity with which it will cling to its usual haunt is remarkable.

Long after the common has been brought under cultivation, it still lingers about the hedgerow, and resorts

to the solitary furze-bush which may have been left a t the corner o f a field or by the roadside. The physical

changes in the surface of the country effected by the progress of agriculture, however beneficial they may

be to the farmer and the husbandman, must in the end lead to the extirpation of many of our native birds.

The Stone-chat may be described as a solitary species; for although several pairs may be found on a

common o f limited extent, two males are seldom seen together; if the females be not sitting on their nest,

the mated birds may be observed facing each other on a neighbouring bush, or first one and then the other

darting off to capture an insect, and returning to the identical sprays they had left. At times, particularly in

spring, the male rises straight up in the air, and descends again with quivering wings, all the while pouring

forth its feeble, pleasing ditty—an expression of joy very different from the chat-chat which it utters when

under the influence of alarm from the presence o f man, or excited by the sight o f any other displeasing object.

During these little paroxysms of anger it becomes very lively, tosses up its head, erects its little tail, and

shakes its rounded wings after the manner of some o f the other Saxicolinee. “ I f you watch its motions,

without alarming it,” says Macgillivray, “ you observe that it flits about by short starts, with a direct flight,

perches on a twig, jerks its body and tail, utters a t intervals a sharp note resembling the syllable snack,

now and then flies off in pursuit of an insect, creeps among the foliage, and sometimes hops along the

ground, or takes its stand on a turf or other eminence.”

On the Continent, this bird, although possessing but limited powers of flight, is a migrant; but few

remaining, according to M. Bailly, in Savoy, or even in Italy, during the winter; in some parts o f Germany

it is said to be scarce a t all times; while in France and other adjacent countries it is very generally

distributed in all dry and uncultivated districts, and there performs the same offices as with us. Two or

three birds of the same form as the Stone-chat inhabit India, one of which was formerly considered identical;

but this, as well as the bird from the Cape of Good Hope, which has also been supposed to be the same, are

now known to be distinct.