¡gf

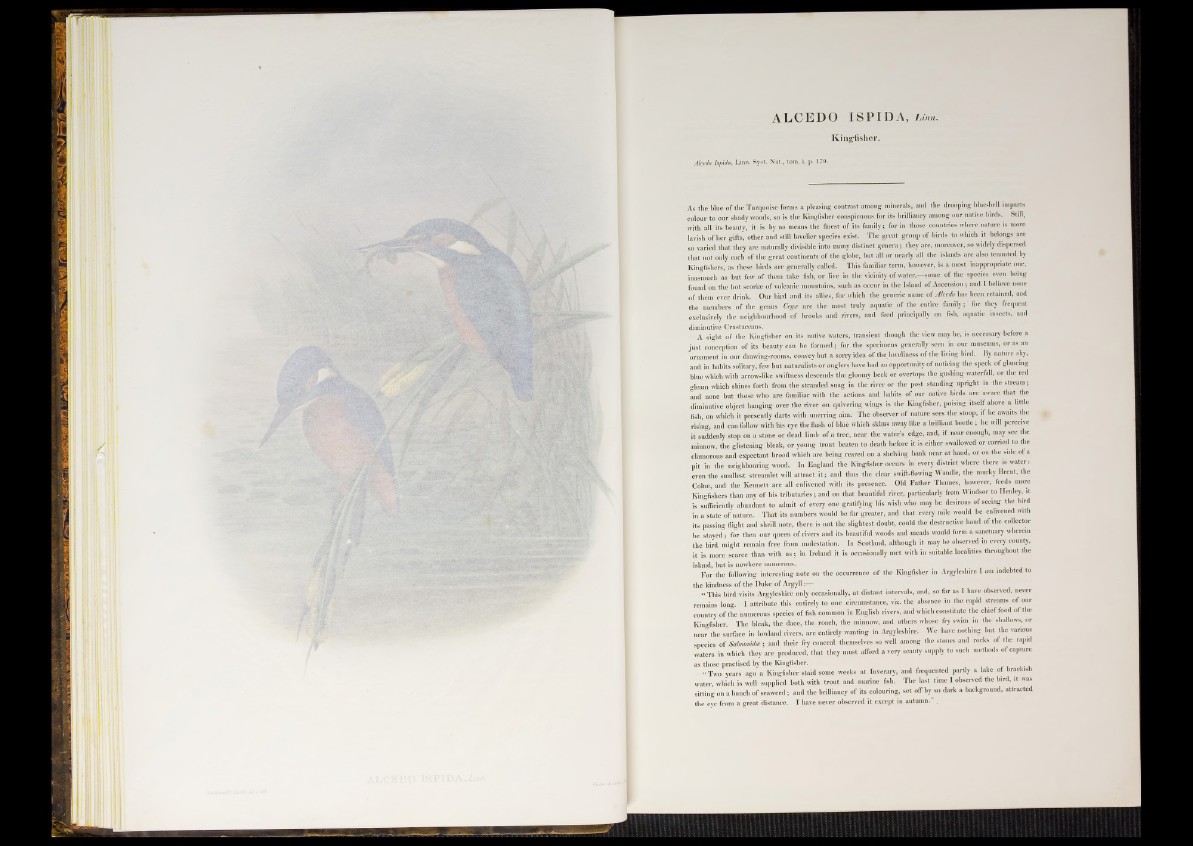

ALCEDO ISPIDA, Linn.

Kingfisher.

Alcedo Ispida, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 179.

As the blue of the Turquoise forms a pleasing contrast among minerals, and the drooping blue-bell imparts

colour to our shady woods, so is the Kingfisher conspicuous for its brilliancy among our native birds. Still,

with all its beauty, it is by no means the finest of its family; for in those countries where nature is more

lavish of her gifts, other and still lovelier species exist. The great group of birds to which it belongs are

so varied that they are naturally divisible into many distinct genera; they are, moreover, so widely dispersed

that not only each of the great continents of the globe, but all or nearly all the islands are also tenanted by

Kingfishers, as these birds are generally called. This familiar term, however, is a most inappropriate one,

inasmuch as but few of them take fish, or live in the vicinity of water,—some of the species even being

found on the hot scoriae o f volcanic mountains, such as occur in the Island of Ascension; and I believe none

of them ever drink. Our bird and its allies, for which the generic name of Alcedo has been retained, and

the members of the genus Ceyx are the most truly aquatic of the entire family; for they frequent

exclusively the neighbourhood o f brooks and rivers, and feed principally on fish, aquatic insects, and

diminutive Crustaceans.

A sight of the Kingfisher on its native waters, transient though the view may be, is necessary before a

ju st conception o f its beauty can be formed; for the specimens generally seen in our museums, or as an

ornament in our drawing-rooms, convey hut a sorry idea o f the.loveliness of the living bird. By nature shy,

and in habits solitary, few but naturalists or anglers have had an opportunity of noticing the speck of glancing

blue which with arrow-like swiftness descends the gloomy heck or overtops the gushing waterfall, or the red

gleam which shines forth from the stranded snag in the river or the post standing upright in the stream;

and none but those who are familiar with the actions and habits of our native birds are aware that the

diminutive object hanging over the river on quivering wings is the Kingfisher, poising itself above a little

fish, on which it presently darts with unerring aim. The observer of nature sees the stoop, if he awaits the

rising, and can follow with his eye the flash of blue which skims away like a brilliant beetle; he will perceive

it suddenly stop on a stone or dead limb of a tree, near the water’s edge, and, if near enough, may see the

minnow, the glistening bleak, or young trout beaten to death before it is either swallowed or carried to the

clamorous and expectant brood which are being reared on a shelving bank near at hand, or on the side of a

pit in the neighbouring wood. In England the Kingfisher occurs in every district where there is water :

even the smallest streamlet will attract i t ; and thus the clear swift-flowing Wandle, the murky Brent, the

Colne, and the Kennett are all enlivened with its presence. Old Father Thames, however, feeds more

Kingfishers than any of his tributaries; and on that beautiful river, particularly from Windsor to Henley, it

is sufficiently abundant to admit of every one gratifying his wish who may be desirous of seeing the bird

in a state of nature. That its numbers would be far greater, and that every mile would be enlivened with

its passing flight and shrill note, there is not the slightest doubt, could the destructive hand of the collector

be stayed; for then our queen of rivers and its beautiful woods and meads would form a sanctuary wherein

the bird might remain free from molestation. In Scotland, although it may be observed in every county,

it is more scarce than with u s ; in Ireland it is occasionally met with in suitable localities throughout the

island, but is nowhere numerous.

For the following interesting note on the occurrence of the Kingfisher in Argyleshire I am indebted to

the kindness of the Duke of Argyll ^ '

“ This bird visits Argyleshire only occasionally, at distant intervals, and, so far as I have observed, never

remains long. I attribute this entirely to one circumstance, viz. the absence in the rapid streams of our

country of the numerous species of fish common in English rivers, and which constitute the chief food of the

Kingfisher. The bleak, the dace, the roach, the minnow, and others whose fry swim in the shallows, or

near the surface in lowland rivers, are entirely wanting in Argyleshire. We have nothing but the various

species of Salmonidee; and their fry conceal themselves so well among the stones and rocks of the rapid

waters in which they are produced, that they must afford a very scanty supply to such methods of capture

as those practised by the Kingfisher.

“ Two years ago a Kingfisher staid some weeks at Inverary, and frequented partly a lake of brackish

water, which is well supplied both with trout and marine fish. The last time I observed the bird, it was

sitting on a bunch of seaweed; and the brilliancy of its colouring, set off by so dark a background, attracted

the eye from a great distance. I have never observed it except in autumn.” .