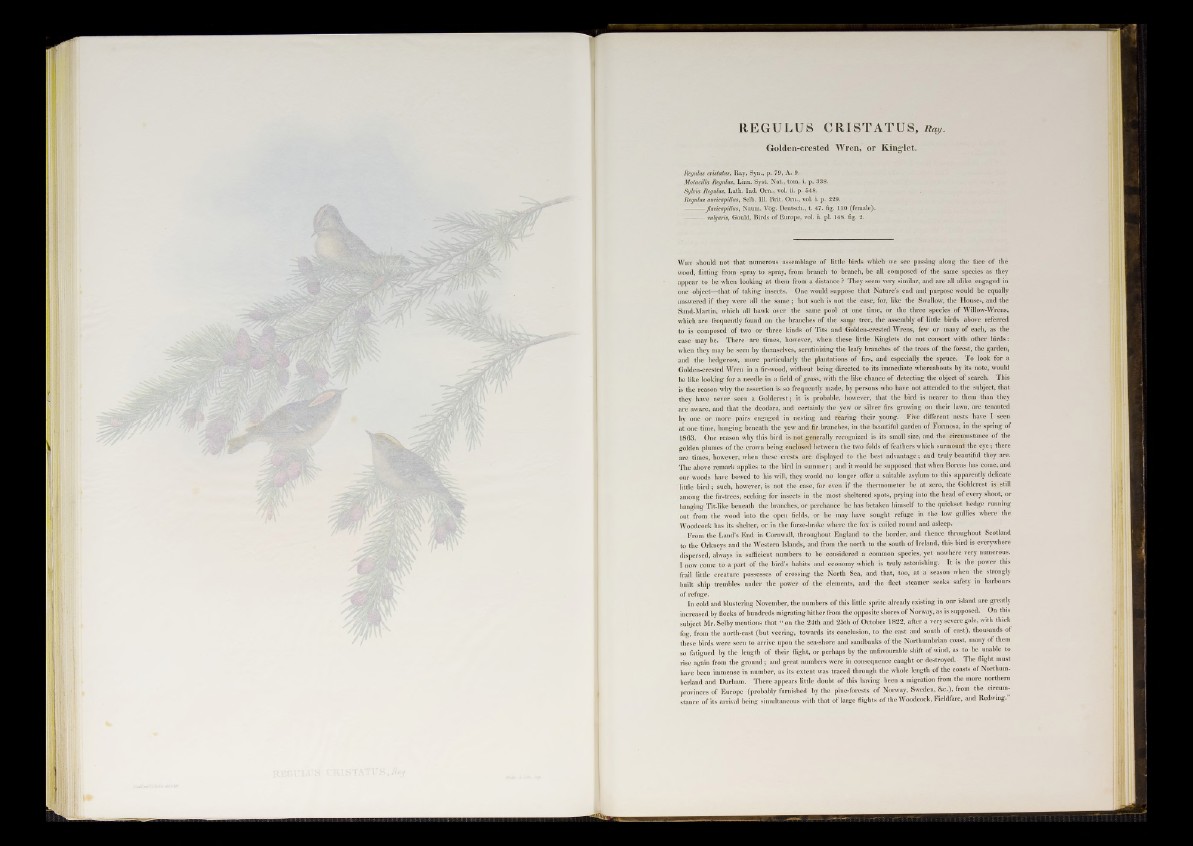

REGULUS CRISTATUS , Raj/.

Golden-crested Wren, or Kinglet.

Regulus cristatus, Ray, Syn., p. 79, A. 9.

Motacilla Regulus, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 338.

Sylvia Regulus, Lath. Ind. Om., vol. ii. p. 548.

Regulus auricapillus, Selb. 111. Brit. Orn., vol. i. p. 229.

flavicapillus, Naum. Vög. Deutsch., t. 47. fig. 110 (female).

vulgaris, Gould, Birds of Europe, vol. ii. pi. 148. fig. 2.

Why should not that numerous assemblage of little birds which we see passing along the face of the

wood, flitting from spray to spray, from branch to branch, be all composed of the same species as they

appear to be when looking at them from a distance ? They seem very similar, and are all alike engaged in

one object—that of taking insects. One would suppose that Nature’s end and purpose would be equally

answered if they were all the same; but such is not the case, for, like the Swallow, the House-, and the

Sand-Martin, which all hawk over the same pool at one time, or the three species of Willow-Wrens,

which are frequently found on the branches of the saime tree, the assembly of little birds above referred

to is composed of two or three kinds of Tits and Golden-crested Wrens, few or many of each, as the

case may be. There are times, however, when these little Kinglets do not consort with other birds:

when they may be seen by themselves, scrutinizing the leafy branches of the trees of the forest, the garden,

and the hedgerow, more particularly the plantations of firs, and especially the spruce. To look for a

Golden-crested Wren in a fir-wood, without being directed to its immediate whereabouts by its note, would

be like looking for a needle in a field of grass, with the like chance of detecting the object of search. This

is the reason why the assertion is so frequently made, by persons who have not attended to the subject, that

they have never seen a Goldcrest; it is probable, however, that the bird is nearer to them than thiey

are aware, and that the deodara, and certainly the yew or silver firs growing on their lawn, are tenanted

by one or more pairs engaged in nesting and rearing their young. Five different nests have I seen

at one time, hanging beneath the yew and fir branches, in the beautiful garden of Formosa, in the spring of

1863. One reason why this bird is not generally recognized is its small size, and the circumstance of the

golden plumes of the crown being enclosed between the two folds of feathers which surmount the eye ;• there

are times, however, when these crests are displayed to the best advantage; and truly beautiful they are.

The above remark applies to the bird in summer; and it would be supposed that when Boreas has come, and

our woods have bowed to his will, they would no longer offer a suitable asylum to this apparently delicate

little b ird ; such, however, is not the case, for even if the thermometer be at zero, the Goldcrest is still

among the fir-trees, seeking for insects in the most sheltered spots, prying into the head of every shoot, or

hanging Tit-like beneath the branches, or perchance he has betaken himself to the quickset hedge running

out from the wood into the opeu fields, or he may have sought refuge in the low gullies where the

Woodcock has its shelter, or in the furze-brake where the fox is coiled round and asleep.

From the Land’s End in Cornwall, throughout England to the border, and thence throughout Scotland

to the Orkneys and the Western Islands, and from the north to the south of Ireland, this bird is everywhere

dispersed, always in sufficient numbers to be considered a common species, yet nowhere very numerous.

I now come to a part of the bird’s habits and economy which is truly astonishing. It is the power this

frail little creature possesses of crossing the North Sea, and that, too, at a season when the strongly

built ship trembles under the power of the elements, and the fleet steamer seeks safety in harbours

of refuge.

In cold and blustering November, the numbers of this little sprite already existing in our island are greatly

increased by flocks of hundreds migrating hither from the opposite shores of Norway, as is supposed. On this

subject Mr. Selby mentions that “ on the 24th and 25th of October 1822, after a very severe gale, with thick

fog, from the north-east (but veering, towards its conclusion, to the east and south of east), thousands of

these birds were seen to arrive upon the sea-shore and sandbanks of the Northumbrian coast, many of them

so fatigued by the length of their flight, or perhaps by the unfavourable shift of wind, as to be unable to

rise again from the ground; and great numbers were in consequence caught or destroyed. The flight must

have been immense in number, as its extent was traced through the whole length of the coasts of Northumberland

and Durham. There appears little doubt of this having been a migration from the more northern

provinces of Europe (probably furnished by the pine-forests of Norway, Sweden, &c.), from the circumstance

of its arrival being simultaneous with that of large flights of the Woodcock, Fieldfare, and Redwing.