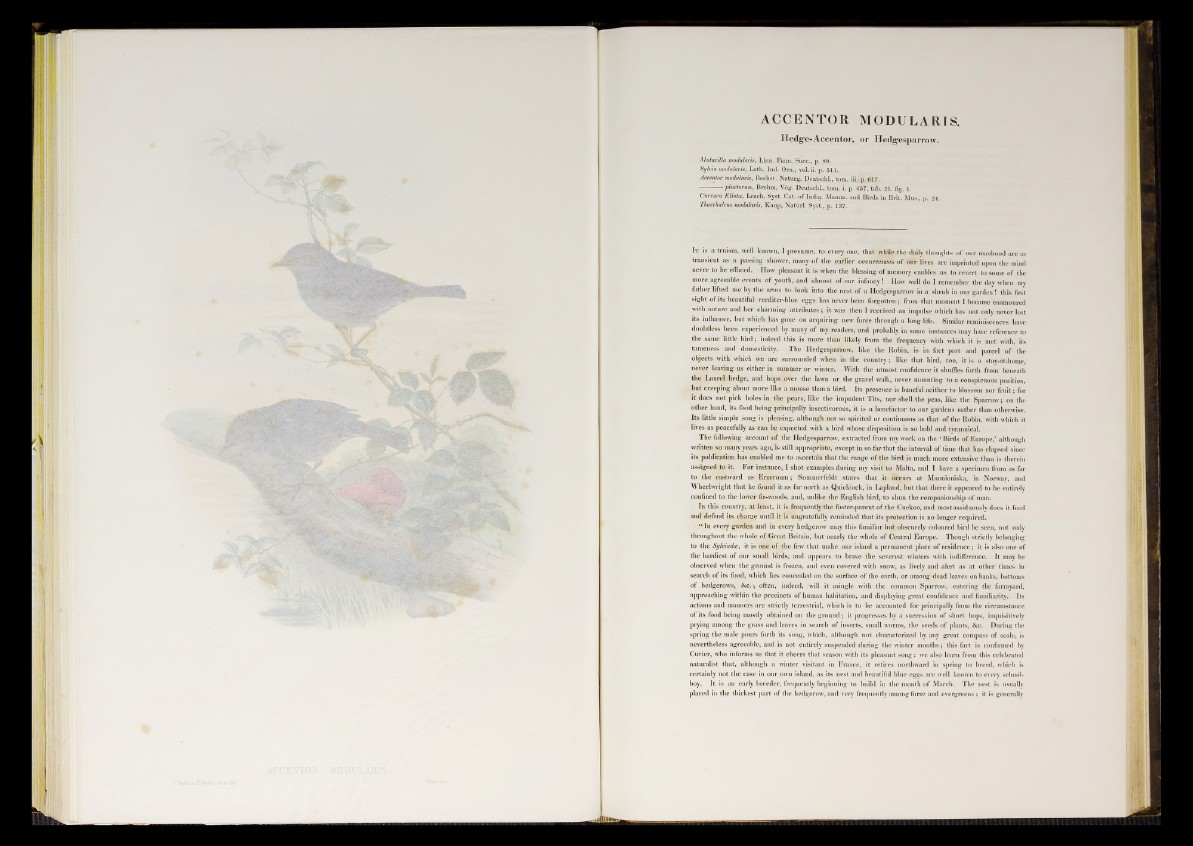

ACCENTOR MODULARIS .

Hedg*e-Accentor, or Hedg*esparrow.

Motacilla modularis, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 89.

Sylvia modularis, Lath. Ind. Orn., vol.ii. p. 511.

Accentor modularis, Bechst. Naturg. Deutschl., tom. iii. p. 617.

— pinetorum, Brehm, Vog. Deutschl., tom. i. p. 457, tab. 21. fig. 1.

Curruca Eliotce, Leach, Syst. Cat. of Indig. Mamm. and Birds in Brit. Mus., p. 24.

Tharrhaleus modularis, Kaup, Natiirl. Syst., p. 137.

It is a truism, well known, I presume, to every one, that while the daily thoughts of our manhood are as

transient as a passing shower, many of the earlier occurrences of our lives are imprinted upon the mind

never to be effaced. How pleasant it is when the blessing of memory enables us to revert to some of the

more agreeable events of youth, and almost of our infancy! How well do I remember the day when my

father lifted me by the arms to look into the nest of a Hedgesparrow in a shrub in our garden! this first

sight o f its beautiful verditer-blue eggs has never been forgotten; from that moment I became enamoured

with nature and her charming attributes; it was then I received an impulse which has not only never lost

its influence, but which has gone on acquiring new force through a long life. Similar reminiscences have

doubtless been experienced by many of my readers, and probably in some instances may have reference to

the same little bird; indeed this is more than likely from the frequency with which it is met with, its

tameness and domesticity. The Hedgesparrow, like the Robin, is in fact part and parcel of the

objects with which we are surrounded when in the country; like that bird, too, it is a stay-at-home,

never leaving us either in summer or winter. With the utmost confidence it shuffles forth from beneath

the Laurel hedge, and hops over the lawn or the gravel walk, never mounting to a conspicuous position,

but creeping about more like a mouse than a bird. Its presence is baneful neither to blossom nor fru it; for

it does not pick holes in the pears, like the impudent Tits, nor shell the peas, like the Sparrow; on the

other hand, its food being principally insectivorous, it is a benefactor to our gardens rather than otherwise.

Its little simple song is pleasing, although not so spirited or continuous as that of the Robin, with which it

lives as peacefully as can he expected with a bird whose disposition is so bold and tyrannical.

The following account of the Hedgesparrow, extracted from my work on the ‘ Birds of Europe,’ although

written so many years ago, is still appropriate, except in so far that the interval of time that has elapsed since

its publication has enabled me to ascertain that the range of the bird is much more extensive than is therein

assigned to it. For instance, I shot examples during my visit to Malta, and I have a specimen from as far

to the eastward as Erzeroum; Sommerfeldt states that it occurs at Muonioniska, in Norway, and

Wheelwright that he found it as far north as Quickiock, in Lapland, but that there it appeared to be entirely

confined to the lower fir-woods, and, unlike the Euglish bird, to shun the companionship of man.

In this country, at least, it is frequently the foster-parent of the Cuckoo, and most assiduously does it feed

and defend its charge until it is ungratefully reminded that its protection is no longer required.

“ In every garden and in every hedgerow may this familiar but obscurely coloured bird be seen, not only

throughout the whole of Great Britain, but nearly the whole of Central Europe. Though strictly belonging

to the Syleiadte, it is one of the few that make our island a permanent place of residence; it is also one of

the hardiest of our small birds, and appears to brave the severest winters with indifference. It may be

observed when the ground is frozen, and even covered with snow, as lively and alert as at other times in

search of its food, which lies concealed on the surface of the earth, or among dead leaves on banks, bottoms

of hedgerows, &c.; often, indeed, will it mingle with the common Sparrow, entering the farmyard,

approaching within the precincts of human habitation, and displaying great confidence and familiarity. Its

actions and manners are strictly terrestrial, which is to be accounted for principally from the circumstance

of its food being mostly obtained on the ground; it progresses by a succession of short hops, inquisitively

prying among the grass and leaves in search of insects, small worms, the seeds of plants, &c. During the

spring the male pours forth its song, which, although not characterized by any great compass of scale, is

nevertheless agreeable, and is not entirely suspended during the winter months; this fact is confirmed by

Cuvier, who informs us that it cheers that season with its pleasant song: we also learn from this celebrated

naturalist that, although a winter visitant in France, it retires northward in spring to breed, which is

certainly not the case in our own island, as its nest and beautiful blue eggs are well known to every schoolboy.

It is an early breeder, frequently beginning to build in the month of March. The nest is usually

placed in the thickest part of the hedgerow, and very frequently among furze and evergreens ; it is generally