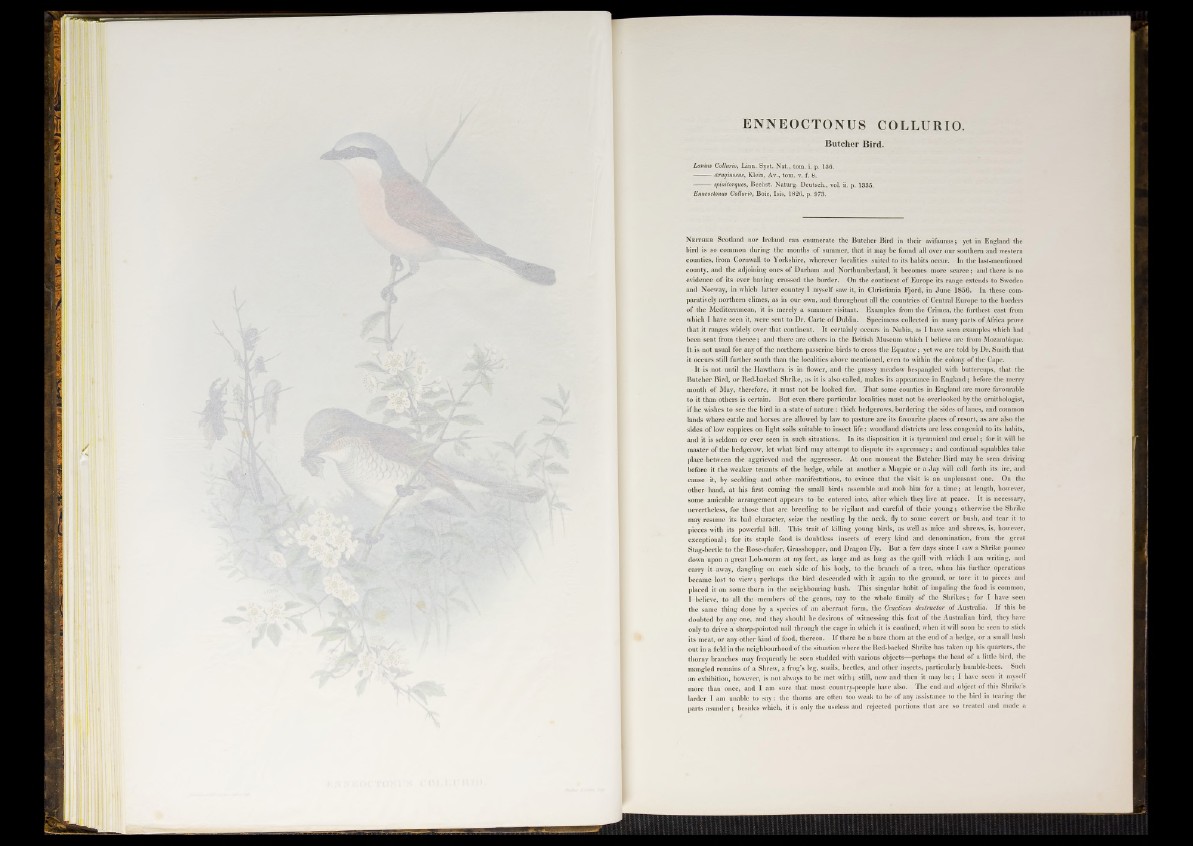

Butcher Bird.

Lanius Collurio, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 136.

eeruginosus, Klein, Av., tom. v. f. 8.

spinitorques, Bechst. Naturg. Deutsch., vol. ii. p. 1335.

Enneoctonus Collurio, Boie, Isis, 1826, p. 973.

N e it h e r Scotland nor Ireland can enumerate the Butcher Bird in their avifaunas; yet in England the

bird is so common during the months of summer, that it may be found all over our southern and western

counties, from Cornwall to Yorkshire, wherever localities suited to its habits occur. In the last-mentioned

county, and the adjoining ones of Durham and Northumberland, it becomes more scarce; and there is no

evidence of its ever having crossed the border. On the continent o f Europe its range extends to Sweden

and Norway, in which latter country I myself saw it, in Christiania Fjord, in June 1856. In these comparatively

northern climes, as in our own, and throughout all the countries of Central Europe to the borders

of the Mediterranean, it is merely a summer visitant. Examples from the Crimea, the furthest east from

which I have seen it, were sent to Dr. Carte of Dublin. Specimens collected in many parts of Africa prove

that it ranges widely over that continent. I t certainly occurs in Nubia, as I have seen examples which had

been sent from thence; and there are others in the British Museum which I believe are from Mozambique.

It is not usual for any of the northern passerine birds to cross the Equator; yet we are told by Dr. Smith that

it occurs still further south than the localities above mentioned, even to within the colony of the Cape.

I t is not until the Hawthorn is in flower, and the grassy meadow bespangled with buttercups, that the

Butcher Bird, or Red-backed Shrike, as it is also called, makes its appearance in England; before the merry

month of May, therefore, it must not be looked for. That some counties in England are more favourable

to it than others is certain. But even there particular localities must not be overlooked by the ornithologist,

if h e wishes to see the bird in a state o f na tu re : thick hedgerows, bordering the sides of lanes, and common

lands where cattle and horses are allowed by law to pasture are its favourite places of resort, as are also the

sides of low coppices on light soils suitable to insect life: woodland districts are less congenial to its habits,

and it is seldom or ever seen in such situations. In its disposition it is tyrannical and cru el; for it will be

master of the hedgerow, let what bird may attempt to dispute its supremacy; and continual squabbles take

place between the aggrieved and the aggressor. At one moment the Butcher Bird may be seen driving

before it the weaker tenants of the hedge, while at another a Magpie or a Jay will call forth its ire, and

cause it, by scolding and other manifestations, to evince that the visit is an unpleasant one. On the

other hand, a t his first coming the small birds assemble and mob him for a time; at length, however,

some amicable arrangement appears to be entered into, after which they live at peace. It is necessary,

nevertheless, for those that are breeding to be vigilant and careful of their young; otherwise the Shrike

may resume its bad character, seize the nestling by the neck, fly to some covert or bush, and tear it to

pieces with its powerful bill. This trait of killing young birds, as well as mice and shrews, is, however,

exceptional; for its staple food is doubtless insects of every kind and denomination, from the great

Stag-beetle to the Rose-chafer, Grasshopper, and Dragon Fly. But a few days since I saw a Shrike pounce

down upon a great Lob-worm a t my feet, as large and as long as the quill with which I am writing, and

carry it away, dangling on each side of his body, to the branch of a tree, when his further operations

became lost to view; perhaps the bird descended with it again to the ground, or tore it to pieces and

placed it on some thorn in the neighbouring bush. This singular habit of impaling the food is common,

I-believe, to all the members of the genus, nay to the whole family of the Shrikes; for I have seen

the same thing done by a species of an aberrant form, the Cracticus destructor o f Australia. I f this be

doubted by any one, and they should be desirous o f witnessing this feat of the Australian bird, they have

only to drive a sharp-pointed nail through the cage in which it is confined, when it will soon be seen to stick

its meat, or any o ther kind o f food, thereon. I f there be a bare thorn at the end o f a hedge, or a small bush

out in a field in the neighbourhood of the situation where the Red-backed Shrike has taken up his quarters, the

thorny branches may frequently be seen studded with various objects—perhaps the head o f a little bird, the

mangled remains of a Shrew, a frog’s leg, snails, beetles, and other insects, particularly humble-bees. Such

an exhibition, however, is not always to be met with; still, now and'then it may be; I have seen it myself

more than once, and I am sure that most country-people have also. The end and .object of this Shrike’s

larder I am unable to say: the thorns are often too weak to be o f any assistance to the bird in tearing the

parts asunder; besides which, it is only the useless and rejected portions that are so treated and made a