Drinkstone Park, informs us that he had seen a blackbird's nest in a Wellington™, and a linnet's in a

Thujopsis.

Culture, Soil, and Propagation—The geological formation of the district in which the Wellingtonias

occur is granitic. Dr C. F. Winslow, in the " Californian Farmer" (8th August 1854). says, that at

Calaveros they are enclosed in a basin of coarse siliceous material, surrounded by a sloping ridge of sienitic

rock, which in some places projects above the soil. The basin is reeking with moisture, and in the lowest

places the water is standing, and some of the largest trees dip their roots into the pools or water-runs.

The soil in which they grow is rich and deep, and if composed, as it probably is, of the decayed

remains of former giants of the same breed, it is no wonder that it is so. Mr Blake alludes to this in one

of the extracts which we have quoted from his paper; and Mr Matthew, in his letter to his father, above

alluded to, says, " The whole surface of the ground (at Calaveros Grove) is strewed with immense trunks,

in many instances covered with vegetation, so as to look like green earthen mounds; and only by cutting

into them one finds that they are composed of rotten wood."

The climate at the Calaveros Grove is good, neither very hot nor very cold, and not dissimilar to our

own. " In this upland region," says Mr Thomas Bannister ("Gardeners' Chronicle," 1855. P- 838). "t he

air is very fine, and the water most pure and cold ; and, after suffering from the excessive heat at Murphy's

and lower down among the southern gold regions, you most reluctantly descend. The wild fruits were not

ripe; but in the season there are, I was told, strawberries, plums, and other fruits in great abundance, verygood

of their kind. There is fine food for cattle." Mr Matthew, in his letter, says, " Amongst the underbrush

are hazel, rasp, currant, gooseberry, dogwood, poplar, and willow, with a number of shrubs which

you do not have in Europe, one of them the Rhus toxodendron, or poison vine." The climate of the

Mariposa Grove is described by Mr Blake as very similar to that of the Calaveros Grove. In summer it

is warm and dry. In winter the snow falls, and rests about six feet deep, but nearly all disappears by the

1 st of May. Rain seldom falls, and he ascribes to this the great depth of soil which hides the rocks. The

snow melts gradually, and runs off without cutting the ground. At the Calaveros Grove the ground

appears to be lower, and much more wet, during the summer, than at the Mariposa ; and at the latter the

trees are more widely spread on the slopes and high knobs of ground, where there is good drainage.

As might be expected, therefore, the climate of this country is perfectly suited to it. When it first

came, it was kept by some in flower-pots, and under glass. The consequence was, that the plants so

treated often became unhealthy and died, unless removed into the open air. It is now universally recognised

as perfectly adapted to the climate of Britain. Merely to say that it is quite hardy in this country

feebly expresses the trust that may be placed on it in this respect. It stood the severe winter of 1860-61,

and also the present (1866-67), in most places without being in the slightest degree touched, even where

plants previously thought hardy were killed by the frost. Of it scarcely a plant was killed, and only a

very few injured, and testimony to its perfect hardiness has poured in from all quarters.

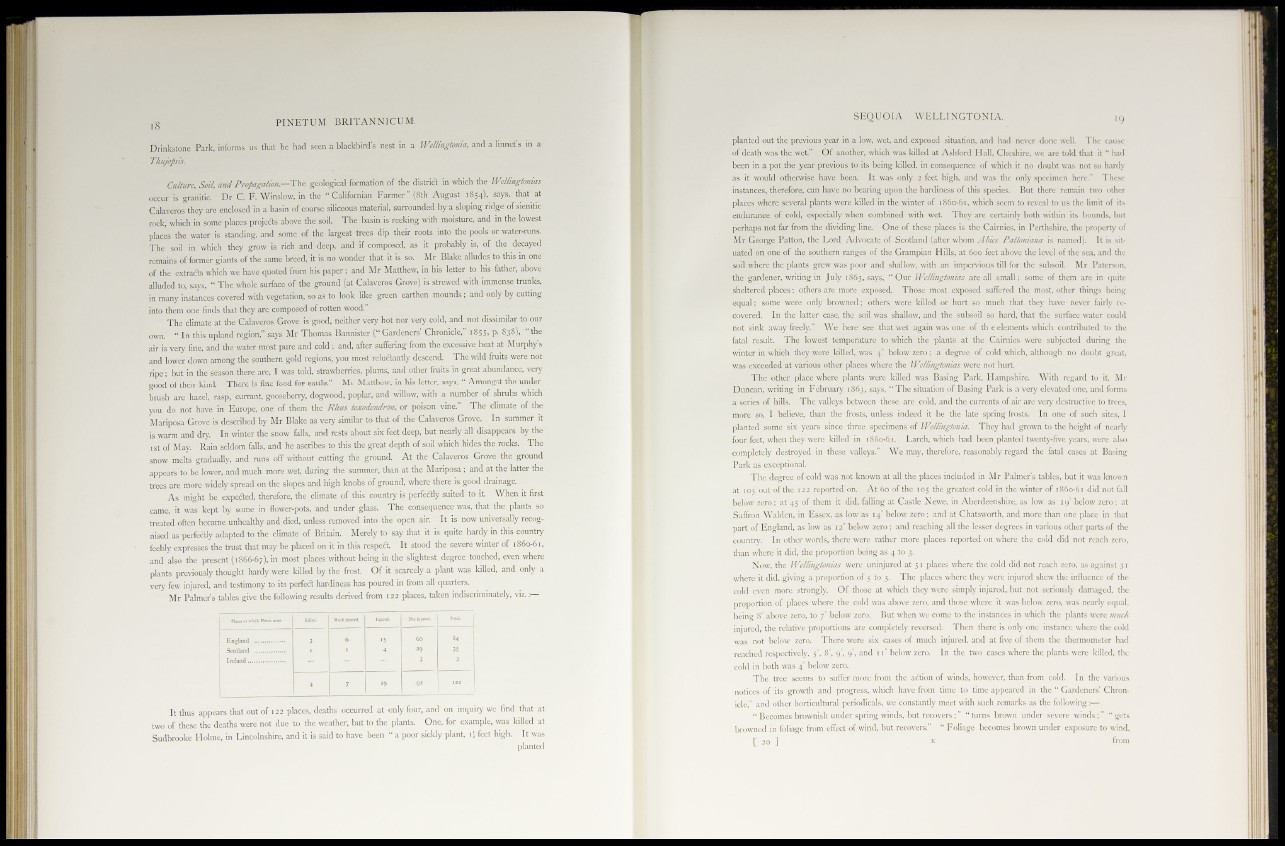

Mr Palmer's tables give the following results derived from 122 places, taken indiscriminately, viz. :—

It thus appears that out of 122 places, deaths occurred at only four, and on inquiry we find that at

two of these the deaths were not due to the weather, but to the plants. One, for example, was killed at

Sudbrooke Holme, in Lincolnshire, and it is said to have been " a poor sickly plant, 13 feet high. It was

planted

planted out the previous year in a low, wet, and exposed situation, and had never done well. The cause

of death was the wet." Of another, which was killed at Ashford Hall, Cheshire, we are told that it " had

been in a pot the year previous to its being killed, in consequence of which it no doubt was not so hardy

as it would otherwise have been. It was only 2 feet high, and was the only specimen here." These

instances, therefore, can have no bearing upon the hardiness of this species. But there remain two other

places where several plants were killed in the winter of 1860-61, which seem to reveal to us the limit of its

endurance of cold, especially when combined with wet. They are certainly both within its bounds, but

perhaps not far from the dividing line. One of these places is the Cairnies, in Perthshire, the property of

Mr George Patton, the Lord Advocate of Scotland (after whom Abies Pattoniana is named). It is situated

on one of the southern ranges of the Grampian Hills, at 600 feet above the level of the sea, and the

soil where the plants grew was poor and shallow, with an impervious till for the subsoil. Mr Paterson,

the gardener, writing in July 1863, says, " Our Wellingtonias are all small; some of them are in quite

sheltered places; others are more exposed. Those most exposed suffered the most, other things being

equal; some were only browned; others were killed or hurt so much that they have never fairly recovered.

In the latter case, the soil was shallow, and the subsoil so hard, that the surface water could

not sink away freely.' We here see that wet again was one of th e elements which contributed to the

fatal result. The lowest temperature to which the plants at the Cairnies were subjected during the

winter in which they were killed, was 4° below zero ; a degree of cold which, although no doubt great,

was exceeded at various other places where the Wellingtonias were not hurt.

The other place where plants were killed was Basing Park, Hampshire. With regard to it, Mr

Duncan, writing in February 1863, says, " The situation of Basing Park is a very elevated one, and forms

a series of hills. The valleys between these are cold, and the currents of air are very destructive to trees,

more so, I believe, than the frosts, unless indeed it be the late spring frosts. In one of such sites, I

planted some six years since three specimens of Wellingtonia. They had grown to the height of nearly

four feet, when they were killed in 1860-61. Larch, which had been planted twenty-five years, were also

completely destroyed in these valleys." We may, therefore, reasonably regard the fatal cases at Basing

Park as exceptional.

The degree of cold was not known at all the places included in Mr Palmer's tables, but it was known

at 105 out of the 122 reported on. At 60 of the 105 the greatest cold in the winter of 1860-61 did not fall

below zero; at 45 of them it did, falling at Castle Newe, in Aberdeenshire, as low as 19' below zero; at

Saffron Walden, in Essex, as low as 14° below zero; and at Chatsworth, and more than one place in that

part of England, as low as 12° below zero : and reaching all the lesser degrees in various other parts of the

country. In other words, there were rather more places reported on where the cold did not reach zero,

than where it did, the proportion being as 4 to 3.

Now. the H'ellingtonias were uninjured at 51 places where the cold did not reach zero, as against 31

where it did, giving a proportion of 5 to 3. The places where they were injured shew the influence of the

cold even more strongly. Of those at which they were simply injured, but not seriously damaged, the

proportion of places where the cold was above zero, and those where it was below zero, was nearly equal,

being 8° above zero, to 7° below zero. But when we come to the instances in which the plants were much

injured, the relative proportions are completely reversed. Then there is only one instance where the cold

was not below zero. There were six cases of much injured, and at five of them the thermometer had

reached respectively, 5°, 8°, 9°, 9°, and 11° below zero. In the two cases where the plants were killed, the

cold in both was 4 below zero.

The tree seems to suffer more from the action of winds, however, than from cold. In the various

notices of its growth and progress, which have from time to time appeared in the " Gardeners' Chronicle,"

and other horticultural periodicals, we constantly meet with such remarks as the following:—

" Becomes brownish under spring winds, but recovers;" "turns brown under severe winds;" "gets

browned in foliage from effect of wind, but recovers." " Foliage becomes brown under exposure to wind,

[ 20 ] K from