denying that the appearance of the timber is against it. It would seem to stand to reason that a soft,

spongy wood cannot be very durable, and we presume we must allow that the wood of the Englishgrown

Cedar sometimes is of that character. A table, which Sir Joseph Banks had made out of the

Hillingdon Cedar, is said by Loudon to have been soft, without scent (except that of common deal),

and possessed little variety of veining; and he mentions that the same remarks applied to a table which

he had made from a plank from one of the trees of Whitton Park. The layers were distinctly marked,

the softer or summer side of each being whitish, loose, and spongy, the harder or winter part being closegrained,

and of a light-brown colour.

The strength of the timber in this country is also no indication of that in its native country. It

seems unquestionable that in the latter it is much greater than in English-grown timber. The old branch

which Sir Joseph Hooker brought from Lebanon gives a totally different idea of the hardness of Cedar

wood from what English-grown specimens do; but as there is no prospect of the Lebanon timber

ever becoming an article of commerce in our days, our practical concern with it is very much limited to

the former.

Loudon tells us that the result of some experiments which he made on the strength of a plant from the

large tree at Whitton, which was blown down in November 1836, was that he found it very inferior in point

of strength to the common English-grown Scotch Pine. The colour and strain of the wood, he adds, were

precisely the same as those of a specimen received by Mr. Lambert from Morocco—that is, of the Cedrus

atlantica. We have in our account of the Deodar given the particulars of a comparative trial of the

strength of that tree and the Cedar, from a specimen presented to the Royal Horticultural Society by Mr.

Tillery, the gardener of the Duke of Portland, where the Deodar had been inarched or grafted on the

Cedar, so that the lower part or stock furnished timber of the Cedar, and the upper part timber of the

Deodar. A piece a foot in length and an inch square was taken from each, within a foot of the spot

where the graft had been made, so that it furnished a portion of the timber of each, which not only had

lived under the same climate, exposure, and other conditions of life, experienced the same degree of

temperature at the same time, had bent to the same blasts, been

frozen by the same cold, thawed by the same sunshine, and

refreshed by the same showers; but were also of the same size and

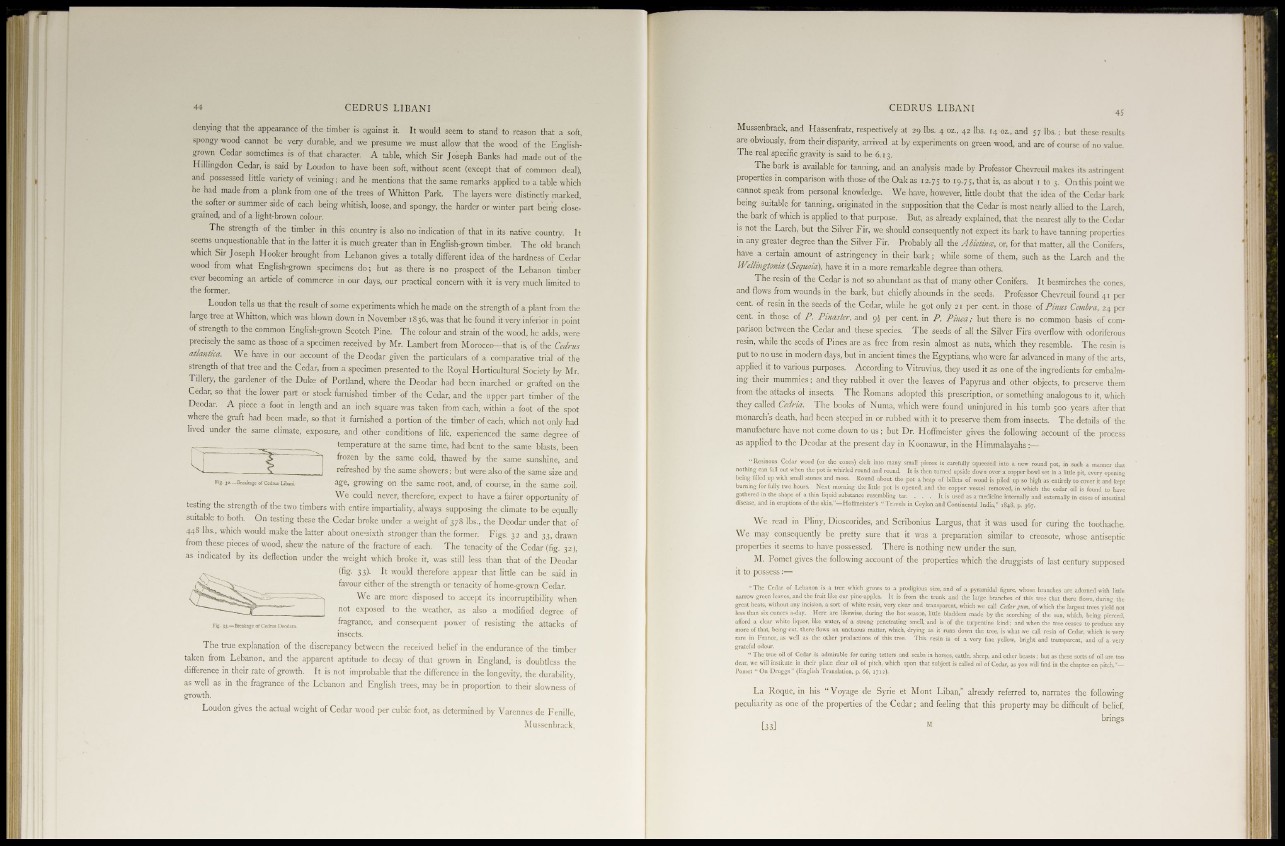

^•s* 3* Breakage of cedrus Libani age, growing on the same root, and, of course, in the same soil.

We could never, therefore, expect to have a fairer opportunity of

testing the strength of the two timbers with entire impartiality, always supposing the climate to be equally

suitable to both. On testing these the Cedar broke under a weight of 378 lbs., the Deodar under that of

448 lbs., which would make the latter about one-sixth stronger than the former. Figs. 32 and 33, drawn

from these pieces of wood, shew the nature of the fracture of each. The tenacity of the Cedar (fig. 32),

as indicated by its deflection under the weight which broke it, was still less than that of the Deodar

(%• 33)- It would therefore appear that little can be said in

favour either of the strength or tenacity of home-grown Cedar.

We are more disposed to accept its incorruptibility when

not exposed to the weather, as also a modified degree of

fragrance, and consequent power of resisting the attacks of

insects.

The true explanation of the discrepancy between the received belief in the endurance of the timber

taken from Lebanon, and the apparent aptitude to decay of that grown in England, is doubtless the

difference in their rate of growth. It is not improbable that the difference in the longevity, the durability,

as well as in the fragrance of the Lebanon and English trees, may be in proportion to their slowness of

growth.

Loudon gives the actual weight of Cedar wood per cubic foot, as determined by Varennes de Fenille,

Mussenbrack,

Mussenbrack, and Hassenfratz, respectively at 29 lbs. 4 oz„ 42 lbs. 14 oz„ and 57 lbs.; but these results

are obviously, from their disparity, arrived at by experiments on green wood, and are of course of no value.

The real specific gravity is said to be 6.13.

The bark is available for tanning, and an analysis made by Professor Chevreuil makes its astringent

properties in comparison with those of the Oak as 12.75 to I 9 .75, that is, as about 1 to 3. On this point we

cannot speak from personal knowledge. We have, however, little doubt that the idea of the Cedar bark

being suitable for tanning, originated in the supposition that the Cedar is most nearly allied to the Larch,

the bark of which is applied to that purpose. But, as already explained, that the nearest ally to the Cedar

is not the Larch, but the Silver Fir, we should consequently not expect its bark to have tanning properties

in any greater degree than the Silver Fir. Probably all the Abietmce, or, for that matter, all the Conifers,

have a certain amount of astringency in their bark; while some of them, such as the Larch and the

Welli?igtonia {Sequoia), have it in a more remarkable degree than others.

The resin of the Cedar is not so abundant as that of many other Conifers. It besmirches the cones,

and flows from wounds in the bark, but chiefly abounds in the seeds. Professor Chevreuil found 41 per

cent, of resin in the seeds of the Cedar, while he got only 21 per cent, in those of Pinus Cembra, 24 per

cent, in those of P. Pinaster, and 9 J per cent, in P. Pinea; but there is no common basis of comparison

between the Cedar and these species. The seeds of all the Silver Firs overflow with odoriferous

resin, while the seeds of Pines are as free from resin almost as nuts, which they resemble. The resin is

put to no use in modern days, but in ancient times the Egyptians, who were far advanced in many of the arts,

applied it to various purposes. According to Vitruvius, they used it as one of the ingredients for embalming

their mummies; and they rubbed it over the leaves of Papyrus and other objects, to preserve them

from the attacks of insects. The Romans adopted this prescription, or something analogous to it, which

they called Cedria. The books of Numa, which were found uninjured in his tomb 500 years after that

monarch's death, had been steeped in or rubbed with it to preserve them from insects. The details of the

manufacture have not come down to us; but Dr. Hoffmeister gives the following account of the process

as applied to the Deodar at the present day in Koonawur, in the Himmalayahs :—

i Cedar wood (or the cones) cleft into many small pieces is carefully squeezed into a new round pot, in such a manner that

I out when the pot is whirled round and round. It is then turned upside down over a copper bowl set in a little pit, every opening

being filled up with small stones and moss. Round about the pot a heap of billets of wood is piled up so high as entirely to cover it and kept

burning for fully two hours. Next morning the little pot is opened, and the copper vessel removed, in which the cedar oil is found to have

gathered in the shape of a thin liquid substance resembling tar. . . . It is used as a medicine internally and externally in cases of intestinal

disease, and in eruptions of the skin."— Hoflmeister's " Travels in Ceylon and Continental India," 184S, p. 367.

We read in Pliny, Dioscorides, and Scribonius Largus, that it was used for curing the toothache.

We may consequently be pretty sure that it was a preparation similar to creosote, whose antiseptic

properties it seems to have possessed. There is nothing new under the sun.

M. Pomet gives the following account of the properties which the druggists of last century supposed

it to possess:—

"The Cedar of Lebanon is a tree which GLUWS LO U prodigious size, and of a pyramidal figure, whose branches arc adorned with little

narrow green leaves, and the fruit like our pine-apples. It is from the trunk and the large branches of this tree that there flows, during the

great heats, without any incision, a sort of white resin, very clear and transparent, which we call Cedar gum, of which the largest trees yield not

less than six ounces a-day. Here are likewise, during the hot season, little bladders made by the scorching of the sun, which, being pierced,

afford a clear white liquor, like water, of a strong penetrating smell, and is of the turpentine kind ; and when the tree ceases to produce any

more of that, being cut, there flows an unctuous matter, which, drying as it runs down the tree, is what we call resin of Cedar, which is very

rare in France, as well as the other productions of this tree. This resin is of a very fine yellow, bright and transparent, and of a very

grateful odour.

The true oil of Cedar is admirable for curing tetters and scabs in horses, cattle, sheep, and other beasts; but as these sorts of oil arc too

dear, we will institute in their place clear oil of pitch, which upon that subject is called oil of Cedar, as you will find in the chapter on pitch."—

Pomet " On Druggs" (English Translation, p. 66, 1712).

La Roque, in his " Voyage de Syrie et Mont Liban," already referred to, narrates the following

peculiarity as one of the properties of the Cedar; and feeling that this property may be difficult of belief,

brings