the authority of the agent, who had been there for fifty-three years, that the late Lord Rochford bought it at

Norwich about a hundred years ago. He adds, " It is certainly a fine specimen, and quite distinct from

C. Libani. We have other small plants of C. Atlantica, purchased from the London nurseries fourteen

years ago, which are the same thing." Mr Irving has had the kindness to forward to us a twig and cone.

The twig has all the characters of C. Atlantica; but the cone [fig. 9], which is very large and fine, corresponds

in outward appearance with that of C. Libani, and not with that of C. Atlantica,

which is smaller and more cylindrical. The wing of the seed, however, has a good

deal of the character of that of C. A tlantica, although we find that sometimes, even

in the same scale, a wing bearing somewhat of the characters of C. Libani is to be

found alongside of one with the form of that of C. Atlantica [see figs. 10 and 11,

which are from the same scale]. On the whole, we believe it to be only a variety of

the Cedar of Lebanon.

Properties and Uses.—The occurrence of this tree on Mount Atlas was doubtless well known to

the Romans, and it was probably of it that some of their choicest furniture was made.

Professor Alphonse De Candolle, writing in 1854, says :—

"The Citrus Atlantica, of which were made the fine tables, Mensa Citrca of Africa, was probably the species of Cedar (Cairns Atlantica)

that we now know to exist in the Atlas. Such a confusion of names was very possible, since, even in our own age, when there are so great pretensions

to know everything, we do not yet know from what tree comes the Palissandre, or Rosewood of Brazil, out of which an immense quantity

of furniture is manufactured. The articles of the Dictionaries of Commerce are absurd on this point; and botanists have only obtained a little

more exact information in 1853. Palissandre probably comes from the words, palo sanlo, holy wood. It appears that the tree is a leguminous

tree of Brazil, of the genus Machtcrium; but the species is doubtful."—Geographic Botanique Raisonnte, vol. ii. p. 864 (1855).

In the Memoirs and Correspondence of Pepys, is a letter (quoted by Loudon, Arboretum, iv.

Suppl., p. 2603) from Evelyn to Pepys, when the latter was at Tangiers, in which he makes the happy

suggestion, " Were it not possible to discover whether any of those Citrine trees are yet to be found that

of old grew about the foot of Mount Atlas, not far from Tingis ? Now, for that some copies in Pliny

read Cedria, others Citria, 'twould be inquired, What sort of Cedar (if any) grows about this mountain ? "

At what time the existence of the Cedar on Mount Atlas was first discovered does not appear. It

was obviously not known when Evelyn wrote this, and it would be curious if its discovery had been due

to his inquiry.

So far as regards its uses in modern times, they are confined to the ordinary applications of timber by

the people of the country. Its value, however, may be expected to become better understood, and Mensa

Citrea may once again perhaps be exported from the Atlas to be loaded with the dishes of the most

civilized peoples of the world.

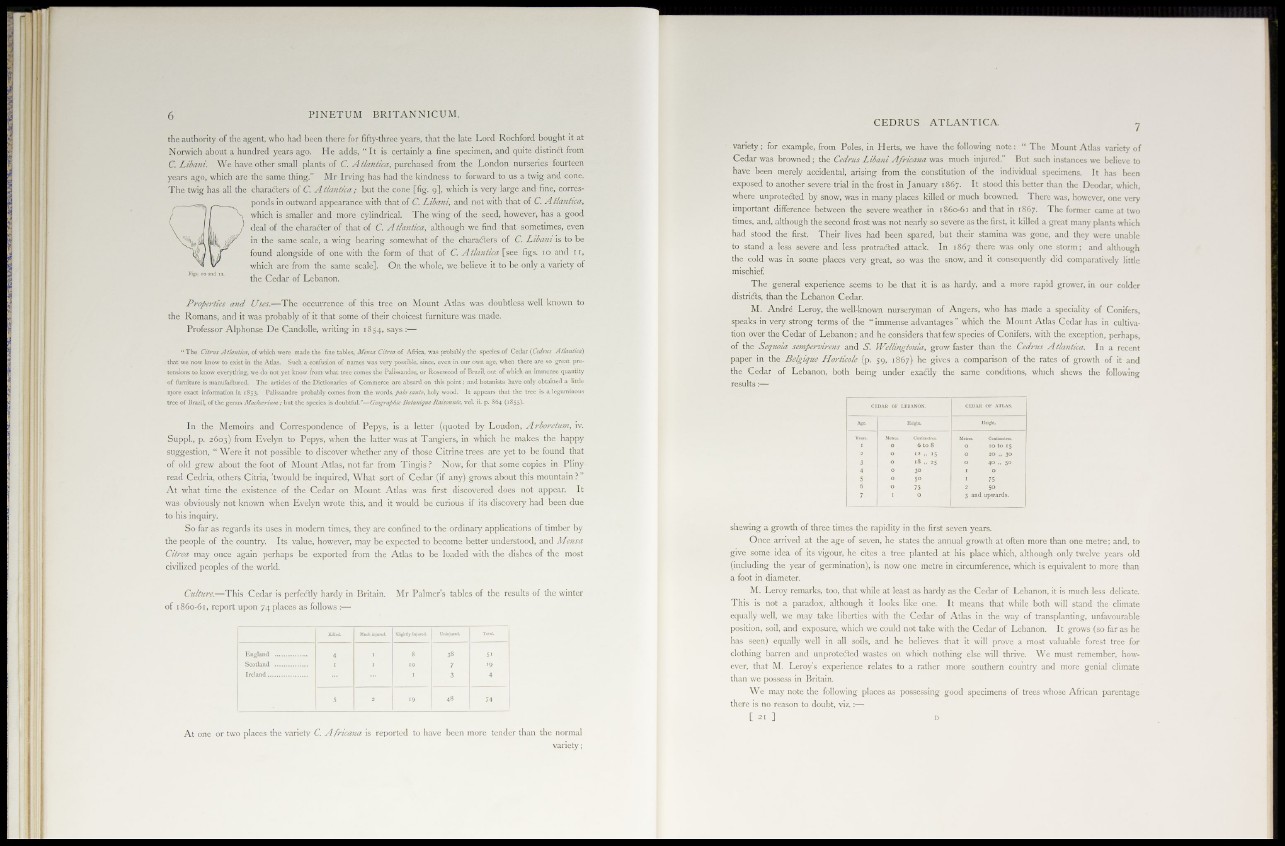

Culture.—This Cedar is perfectly hardy in Britain. Mr Palmer's tables of the results of the winter

of 1860-61, report upon 74 places as follows :—

At one or two places the variety C. Africana is reported to have been more tender than the normal

variety;

CEDRUS A T L A N T I CA 7

variety ; for example, from Poles, in Herts, we have the following note: " The Mount Atlas variety of

Cedar was browned ; the Cedrus Libani Africana was much injured." But such instances we believe to

have been merely accidental, arising from the constitution of the individual specimens. It has been

exposed to another severe trial in the frost in January 1867. It stood this better than the Deodar, which,

where unprotected by snow, was in many places killed or much browned. There was, however, one very

important difference between the severe weather in 1860-61 and that in 1867. The former came at two

times, and, although the second frost was not nearly so severe as the first, it killed a great many plants which

had stood the first. Their lives had been spared, but their stamina was gone, and they were unable

to stand a less severe and less protracted attack. In 1867 there was only one storm; and although

the cold was in some places very great, so was the snow, and it consequently did comparatively little

mischief.

The general experience seems to be that it is as hardy, and a more rapid grower, in our colder

districts, than the Lebanon Cedar.

M. André Leroy, the well-known nurseryman of Angers, who has made a speciality of Conifers,

speaks in very strong terms of the " immense advantages " which the Mount Atlas Cedar has in cultivation

over the Cedar of Lebanon; and he considers that few species of Conifers, with the exception, perhaps,

of the Sequoia sempervirens and S. Wellingtonia, grow faster than the Cedrus Atlantica. In a recent

paper in the Belgique Horticole (p. 59, 1867) he gives a comparison of the rates of growth of it and

the Cedar of Lebanon, both being under exactly the same conditions, which shews the following

results :—

shewing a growth of three times the rapidity in the first seven years.

Once arrived at the age of seven, he states the annual growth at often more than one metre; and, to

give some idea of its vigour, he cites a tree planted at his place which, although only twelve years old

(including the year of germination), is now one metre in circumference, which is equivalent to more than

a foot in diameter.

M. Leroy remarks, too, that while at least as hardy as the Cedar of Lebanon, it is much less delicate.

This is not a paradox, although it looks like one. It means that while both will stand the climate

equally well, we may take liberties with the Cedar of Atlas in the way of transplanting, unfavourable

position, soil, and exposure, which we could not take with the Cedar of Lebanon. It grows (so far as he

has seen) equally well in all soils, and he believes that it will prove a most valuable forest tree for

clothing barren and unprotected wastes on which nothing else will thrive. We must remember, however,

that M. Leroy's experience relates to a rather more southern country and more genial climate

than we possess in Britain.

We may note the following places as possessing good specimens of trees whose African parentage

there is no reason to doubt, viz.:—