Lower Miocene), and was first described by Unger; but his description is extremely meagre, and without

any figure. Goeppert, however, in his monograph of Fossil Conifers, says, after reproducing Unger's

short description, that he remembers to have seen, in Schlotheim's collection (now incorporated in the

Berlin Museum), a specimen of a damaged cone, whose whole form was remarkably suggestive of the

Lebanon or the Deodar Cedar.*

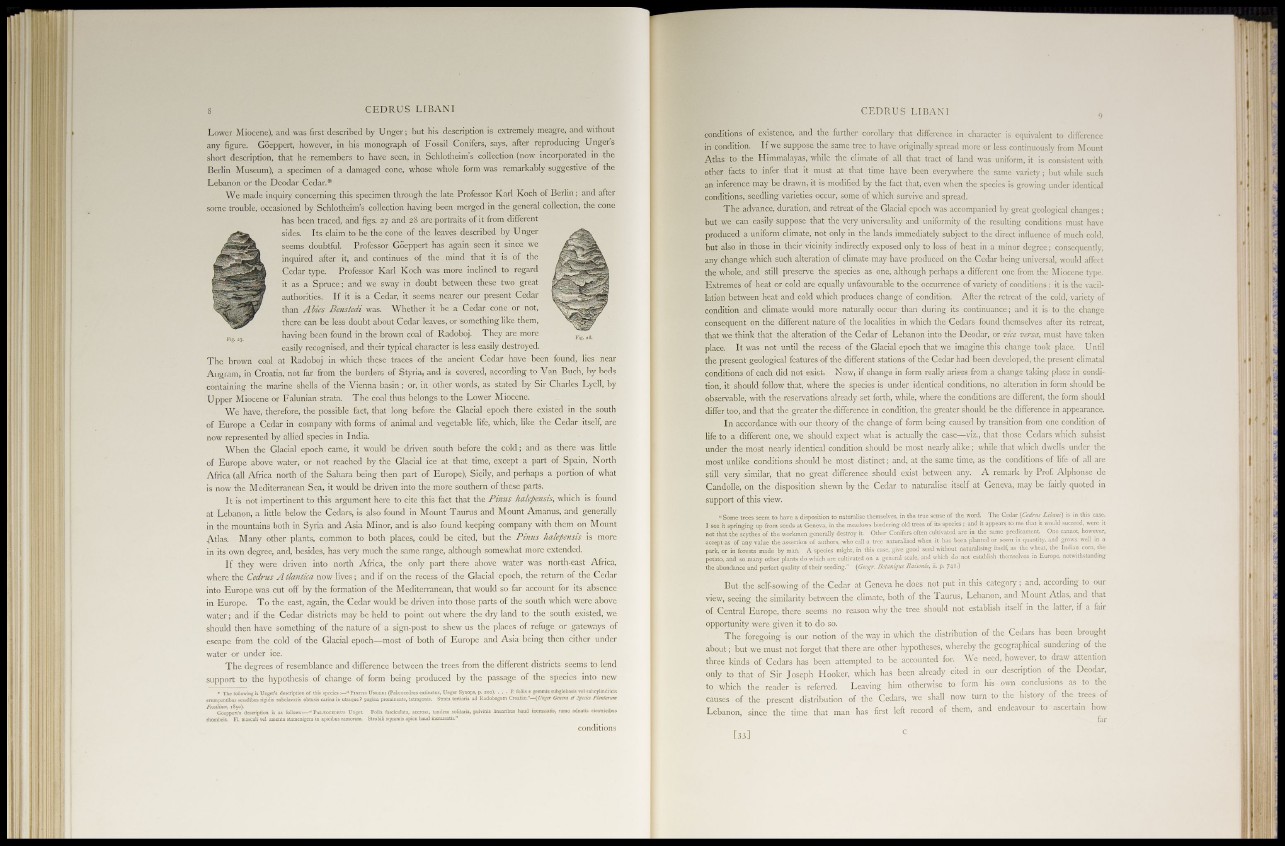

We made inquiry concerning this specimen through the late Professor Karl Koch of Berlin; and after

some trouble, occasioned by Schlotheim's collection having been merged in the general collection, the cone

has been traced, and figs. 27 and 28 are portraits of it from different

sides. Its claim to be the cone of the leaves described by Unger

seems doubtful. Professor Goeppert has again seen it since we

inquired after it, and continues of the mind that it is of the

Cedar type. Professor Karl Koch was more inclined to regard

it as a Spruce; and we sway in doubt between these two great

authorities. If it is a Cedar, it seems nearer our present Cedar

than Abies Benstedi was. Whether it be a Cedar cone or not,

there can be less doubt about Cedar leaves, or something like them,

having been found in the brown coal of Radoboj. They are more

easily recognised, and their typical character is less easily destroyed.

The brown coal at Radoboj in which these traces of the ancient Cedar have been found, lies near

Angram, in Croatia, not far from the borders of Styria, and is covered, according to Van Buch, by beds

containing the marine shells of the Vienna basin; or, in other words, as stated by Sir Charles Lyell, by

Upper Miocene or Falunian strata. The coal thus belongs to the Lower Miocene.

We have, therefore, the possible fact, that long before the Glacial epoch there existed in the south

of Europe a Cedar in company with forms of animal and vegetable life, which, like the Cedar itself, arc

now represented by allied species in India.

When the Glacial epoch came, it would be driven south before the cold; and as there was little

of Europe above water, or not reached by the Glacial ice at that time, except a part of Spain, North

Africa (all Africa north of the Sahara being then part of Europe), Sicily, and perhaps a portion of what

is now the Mediterranean Sea, it would be driven into the more southern of these parts.

It is not impertinent to this argument here to cite this fact that the Pinus halepensis, which is found

at Lebanon, a little below the Cedars, is also found in Mount Taurus and Mount Amanus, and generally

in the mountains both in Syria and Asia Minor, and is also found keeping company with them on Mount

Atlas. Many other plants, common to both places, could be cited, but the Pinus halepensis is more

in its own degree, and, besides, has very much the same range, although somewhat more extended.

If they were driven into north Africa, the only part there above water was north-east Africa,

where the Cedrus A tlantica now lives ; and if on the recess of the Glacial epoch, the return of the Cedar

into Europe was cut off by the formation of the Mediterranean, that would so far account for its absence

in Europe. To the east, again, the Cedar would be driven into those parts of the south which were above

water; and if the Cedar districts may be held to point out where the dry land to the south existed, we

should then have something of the nature of a sign-post to shew us the places of refuge or gateways of

escape from the cold of the Glacial epoch—most of both of Europe and Asia being then cither under

water or under ice.

The degrees of resemblance and difference between the trees from the different districts seems to lend

support to the hypothesis of change of form being produced by the passage of the species into new

conditions of existence, and the further corollary that difference in character is equivalent to difference

in condition. If we suppose the same tree to have originally spread more or less continuously from Mount

Atlas to the Himmalayas, while the climate of all that tract of land was uniform, it is consistent with

other facts to infer that it must at that time have been everywhere the same variety; but while such

an inference may be drawn, it is modified by the fact that, even when the species is growing under identical

conditions, seedling varieties occur, some of which survive and spread.

The advance, duration, and retreat of the Glacial epoch was accompanied by great geological changes;

but we can easily suppose that the very universality and uniformity of the resulting conditions must have

produced a uniform climate, not only in the lands immediately subject to the direct influence of much cold,

but also in those in their vicinity indirectly exposed only to loss of heat in a minor degree; consequently,

any change which such alteration of climate may have produced on the Cedar being universal, would affect

the whole, and still preserve the species as one, although perhaps a different one from the M iocene type.

Extremes of heat or cold are equally unfavourable to the occurrence of variety of conditions: it is the vacillation

between heat and cold which produces change of condition. After the retreat of the cold, variety of

condition and climate would more naturally occur than during its continuance; and it is to the change

consequent on the different nature of the localities in which the Cedars found themselves after its retreat,

that we think that the alteration of the Cedar of Lebanon into the Deodar, or vice versa, must have taken

place. It was not until the recess of the Glacial epoch that we imagine this change took place. Until

the present geological features of the different stations of the Cedar had been developed, the present climatal

conditions of each did not exist. Now, if change in form really arises from a change taking place in condition,

it should follow that, where the species is under identical conditions, no alteration in form should be

observable, with the reservations already set forth, while, where the conditions are different, the form should

differ too, and that the greater the difference in condition, the greater should be the difference in appearance.

In accordance with our theory of the change of form being caused by transition from one condition of

life to a different one, we should expect what is actually the case—viz., that those Cedars which subsist

under the most nearly identical condition should be most nearly alike; while that which dwells under the

most unlike conditions should be most distinct; and, at the same time, as the conditions of life of all are

still very similar, that no great difference should exist between any. A remark by Prof. Alphonse de

Candolle, on the disposition shewn by the Cedar to naturalise itself at Geneva, may be fairly quoted in

support of this view.

"Some trees seem to have a disposition to naturalise themselves, in the true sense of the word. The Cedar (Cedrus Libani) is in this case.

I see it springing up from seeds at Geneva, in the meadows bordering old trees of its species; and it appears to me that it would succeed, were it

not that the scythes of the workmen generally destroy it. Other Conifers often cultivated are in the same predicament. One cannot, however,

accept as of any value the assertion of authors, who call a tree naturalised when it has been planted or sown in quantity, and grows well in a

park, or in forests made by man. A species might, in this case, give good seed without naturalising itself, as the wheat, the Indian corn, the

potato, and so many other plants do which are cultivated on a general scale, and which do not establish themselves in Europe, notwithstanding

the abundance and perfect quality of their seeding." (Geogr. Dotanique Raisonle, ii. p. 741.)

But the self-sowing of the Cedar at Geneva he does not put in this category ; and, according to our

view, seeing the similarity between the climate, both of the Taurus, Lebanon, and Mount Atlas, and that

of Central Europe, there seems no reason why the tree should not establish itself in the latter, if a fair

opportunity were given it to do so.

The foregoing is our notion of the way in which the distribution of the Cedars has been brought

about; but we must not forget that there are other hypotheses, whereby the geographical sundering of the

three kinds of Cedars has been attempted to be accounted for. We need, however, to draw attent.on

only to that of Sir Joseph Hooker, which has been already cited in our description of the Deodar,

to which the reader is referred. Leaving him otherwise to form his own conclusions as to the

causes of the present distribution of the Cedars, we shall now turn to the history of the trees of

Lebanon, since the time that man has first left record of them, and endeavour to ascertain how

far