of one of these trees, viz., that known as the " Old Maid." This tree had been broken off by a storm at

a height of 128 feet, and its base cut across now serves as a dancing floor. M. De la Rue measured the

annual rings in the following way: a slip of paper was stretched across the diameter of the trunk, the

annual rings being marked off with a pencil on the paper, according to the convenient method originally

proposed by Augustus Pyramus de Candolle. He found that the diameter at the height of about six feet

was 26 feet 5 inches. The entire height of the tree, before it was broken by the wind, was, approximately,

350 feet. The number of rings was counted by M. De la Rue and his assistant, one going from the

circumference to the centre, the other in the opposite direction. The one counted 1223 rings, the other

1245. The mean of the two observations, which is no doubt nearly correct, gives the tree an age of 1234

years, which is not an extraordinary one for trees, especially Conifers. There are, for instance, Yew trees

which date back from the Christian era. The Sequoias grow in a deep and rich soil, and their rate of

growth appears to have been very uniform. Thus, on the slip of paper it might be seen that, at the age of

400 to 500 years, the annual rings were still thick, while in ordinary trees the layer becomes thin at from 80

to 120 years, according to the kind of tree and other circumstances.

But although the individual specimens whose rings have been counted were only about 1200 years

old, we do not think that it by any means follows that that is the extreme measure of the life of the tree.

In the first place, there is no physical impossibility in their reaching a much greater age. The Yew trees

above referred to are an evidence that allied trees do, and we think there is good ground for holding that

the oldest Cedars in the grove at Lebanon exceed 2000 years in age. Besides this, there are Wellingtonias

much larger than those whose rings have been measured. " The Father of the Forest," above

spoken of, was a third larger, and it seems only reasonable to infer, that he should have been at least a

third older. The growth of the annual rings misleads us in our calculations of age only when it is misapplied.

They diminish in breadth as we go outwards. Therefore, if we take the outer rings, and, finding

that so many occur in an inch, estimate the whole interior of the tree at the same rate, we must necessarily

overrate their number; in the same way that we should equally underrate their number if we started

from the centre and reckoned only from the breadth of a few of the inner rings.

The tree, the breadths of whose rings are above given by Dr Torrey, measured 23 feet in diameter,

and that by Professor de Candolle 263, or about 75 feet in circumference. The girth of " The Father of

the Forest," even as now left, is 110 or 112 feet. It therefore must have had a diameter of 1 ij feet more

than Dr Torrey's, which, to equal it, would require a circlet of 6 feet additional to be applied all the

way round the trunk of the tree. How many annual rings would it take to make up this additional

diameter ?

It is clear that if we take the rate of growth at which his tree was growing when cut down, that is, the

outer rings, we shall not over-estimate the number; any that would have grown after them must have been

smaller in breadth, not greater. We must, however, take it fairly; and as in it there was a sudden diminution

of a&ive growth during the last hundred years, it having only grown an inch during that period, in

opposition to about a foot in each of the previous hundred years for some centuries previously, we think it

would be scarcely fair to take the inch as the standard for every future hundred years' growth. We regard

the inch in the final hundred rather as the indication that the tree had reached its maturity, and had, what

in man is called, "stopped growing;" and we suppose that until it reached this period of decadence, it went

on growing at the rate of a foot in a hundred years without allowing for any small addition after having

stopped growing. This would give us upwards of 2000 years as the period of life of the " Father of the

Forest;" but as we have 100 years to add to Dr Torrey's for an inch after cessation of adive growth,

some allowance of a similar nature should be made in this case too, which might bring its age up a few

hundred years more. If we were to take that last 100 years' growth as the normal rate after a tree had

reached 25 feet in diameter, it would make the age of the " Father of the Forest" 8200 years, or even

more ; for, small as the breadth of the annual rings taken to start with is, they would still go on progressively

diminishing ad infinitum.

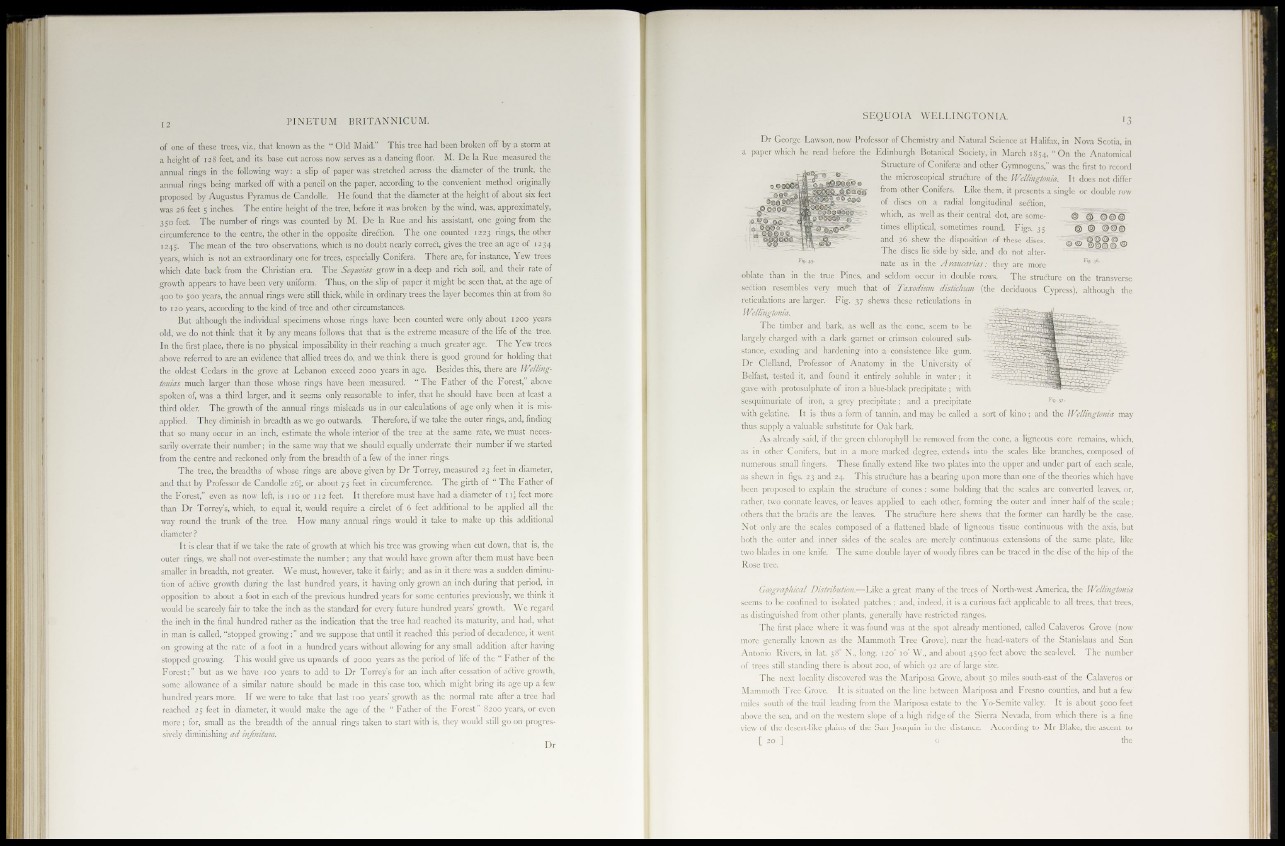

Dr George Lawson, now Professor of Chemistry and Natural Science at Halifax, in Nova Scotia, in

a paper which he read before the Edinburgh Botanical Society, in March 1854, "On the Anatomical

Structure of Conifene and other Gymnogens," was the first to record

the microscopical structure of the Wellingtonia. It does not differ

from other Conifers. Like them, it presents a single or double row

of discs on a radial longitudinal sedion,

which, as well as their central dot, are some- ® © @©@

times elliptical, sometimes round. Figs. 35 ® © ©@©

and 36 shew the disposition of these discs. © ® @QQ Q ©

The discs lie side by side, and do not alternate

as in the Araucarias: they are more

oblate than in the true Pines, and seldom occur in double rows. The structure on the transverse

section resembles very much that of Taxodium distichum (the deciduous Cypress), although the

reticulations are larger. Fig, 37 shews these reticulations in

Wellingtonia.

The timber and bark, as well as the cone, seem to be

largely charged with a dark garnet or crimson coloured substance,

exuding and hardening into a consistence like gum.

Dr Clclland, Professor of Anatomy in the University of

Belfast, tested it, and found it entirely soluble in water; it

gave with protosulphate of iron a blue-black precipitate ; with

sesquimuriate of iron, a grey precipitate ; and a precipitate

with gelatine. It is thus a form of tannin, and may be called a sort of kino ; and the Wellingtonia may

thus supply a valuable substitute for Oak bark.

As already said, if the green chlorophyll be removed from the cone, a ligneous core remains, which,

as in other Conifers, but in a more marked degree, extends into the scales like branches, composed of

numerous small fingers. These finally extend like two plates into the upper and under part of each scale,

as shewn in figs. 23 and 24. This structure has a bearing upon more than one of the theories which have

been proposed to explain the structure of cones : some holding that the scalcs are converted leaves, or,

rather, two connate leaves, or leaves applied to each other, forming the outer and inner half of the scale;

others that the bracts are the leaves. The structure here shews that the former can hardly be the case.

Not only are the scales composed of a flattened blade of ligneous tissue continuous with the axis, but

both the outer and inner sides of the scales are merely continuous extensions of the same plate, like

two blades in one knife. The same double layer of woody fibres can be traced in the disc of the hip of the

Rose tree.

Geographical Distribution.—Like a great many of the trees of North-west America, the Wellingtonia

seems to be confined to isolated patches ; and, indeed, it is a curious fact applicable to all trees, that trees,

as distinguished from other plants, generally have restricted ranges.

The first place where it was found was at the spot already mentioned, called Calaveros Grove (now

more generally known as the Mammoth Tree Grove), near the head-waters of the Stanislaus and San

Antonio Rivers, in lat. 38° N., long. 120° 10' W., and about 4590 feet above the sea-level. The number

of trees still standing there is about 200, of which 92 are of large size.

The next locality discovered was the Mariposa Grove, about 50 miles south-east of the Calaveros or

Mammoth Tree Grove. It is situated on the line between Mariposa and Fresno counties, and but a few

miles south of the trail leading from the Mariposa estate to the Yo-Semite valley. It is about 5000 feet

above the sea, and on the western slope of a high ridge of the Sierra Nevada, from which there is a fine

view of the desert-like plains of the San Joaquin in (he distance. According to Mr Blake, the ascent to

[ 20 ] c. the