SEQUOIA WELLINGTONIA.

appears an inevitable corollary that, if these, which have many salient points of distinction, should be

merged together, a fortiori, Wellingtonia and Sequoia, which have almost none, should be united too.

It is unnecessary to say that the converse of the proposition does not hold: it is no reason that,

because species differing little from each other should be classed together, those differing much should be

so too.

At the early stage of the controversy (if it can be called so), we had adopted the views entertained by

Dr Lindley. We had then seen the living plants only in their normal form, large, full-grown cones of the

Wellingtonia, small stunted cones of Sequoia sempervirens, and no male flowers of the former. We considered

the very marked apparent difference in the foliage to be sufficient, along with the difference in the

cones, to constitute a distind genus. We have now, with better material, come to a different conclusion.

The materials which have convinced us that Wellingtonia gigantea belongs to the same genus as Sequoia

sempervirens are, first, the male flowers. It is only now in the present season (1866) that we have at last

seen them. Doubtless, specimens must have been procured by botanists from the aboriginal trees themselves

in the course of the last ten or fifteen years, during which they have been known to men of science,

and been objects of interest and constantly visited ; but we never happen to have seen any; nor have wc

met with any description or figure of them. Indeed, we believe that the figures which we now give of

them are the first which have been published. There were none in the British Museum or at Kew. At

Kew, indeed, there was a tantalising specimen which had possessed a few male flowers; but they are very

decadent, and the flowers of the specimen in question had all fallen off, leaving nothing but the stalk on

which they had once grown. It was, therefore, with eagerness that we watched the young plants in this

country when they began to shew symptoms of bearing fruit. It is now two or three years since cones were

observed; but until 1866 no male flowers made their appearance. The first observer who drew attention

to them was Mr Andrew Gilchrist, forester, Tilliechewan Castle, Dumbartonshire; and the next, Mr Cox,

gardener to Mr Wells of Red Leaf, who exhibited fine specimens both of cones and flowers to the Royal

Horticultural Society; but almost immediately afterwards, other notices of their occurrence appeared, and

we received specimens from various quarters. On an examination of these, it is plain that they are in all

v respects identical in structure and form with those of Sequoia _

A (Sk^) \\ sempervirens. Fig. 27 shews the catkin of the Wellingtonia of | >

1 X 0 M the natural size, and fig. 28 that of the S. sempervirens; and | »

3 a Fi , h Fi figs. 29 a b c the scales of the Wellingtonia, and 30 a b c those ffl <f

Flower wm^ ,>f five, sempervirens, in different positions. From these it will be _ v

seen that there is little difference except in size; the catkins of

% \\ sempervirens being merely a little larger than the other: the flowers in this respect

T J reversing the character of the cones, which are larger in Wellingtonia. The scales

,0, Fig. 3oIk Fig. , 0 a r e , however, largest in Wellingtonia, and less jagged at the edges; the anthers, on

the other hand, are largest in S. sempervirens. The only thing approaching a

structural difference is, that in those which we have examined the anthers in Wellingtonia were borne

inside the scale, while in 5. sempervirens they were turned backwards and borne on the back; but both

proceed from the free under-margin of the scale, and we have no doubt that this apparent difference in

position is due to the different age of the specimens, and that when Wellingtonia is farther advanced its

anthers will be turned farther back too. So far, therefore, as regards the male flowers, it is impossible to

ground any separation upon them.

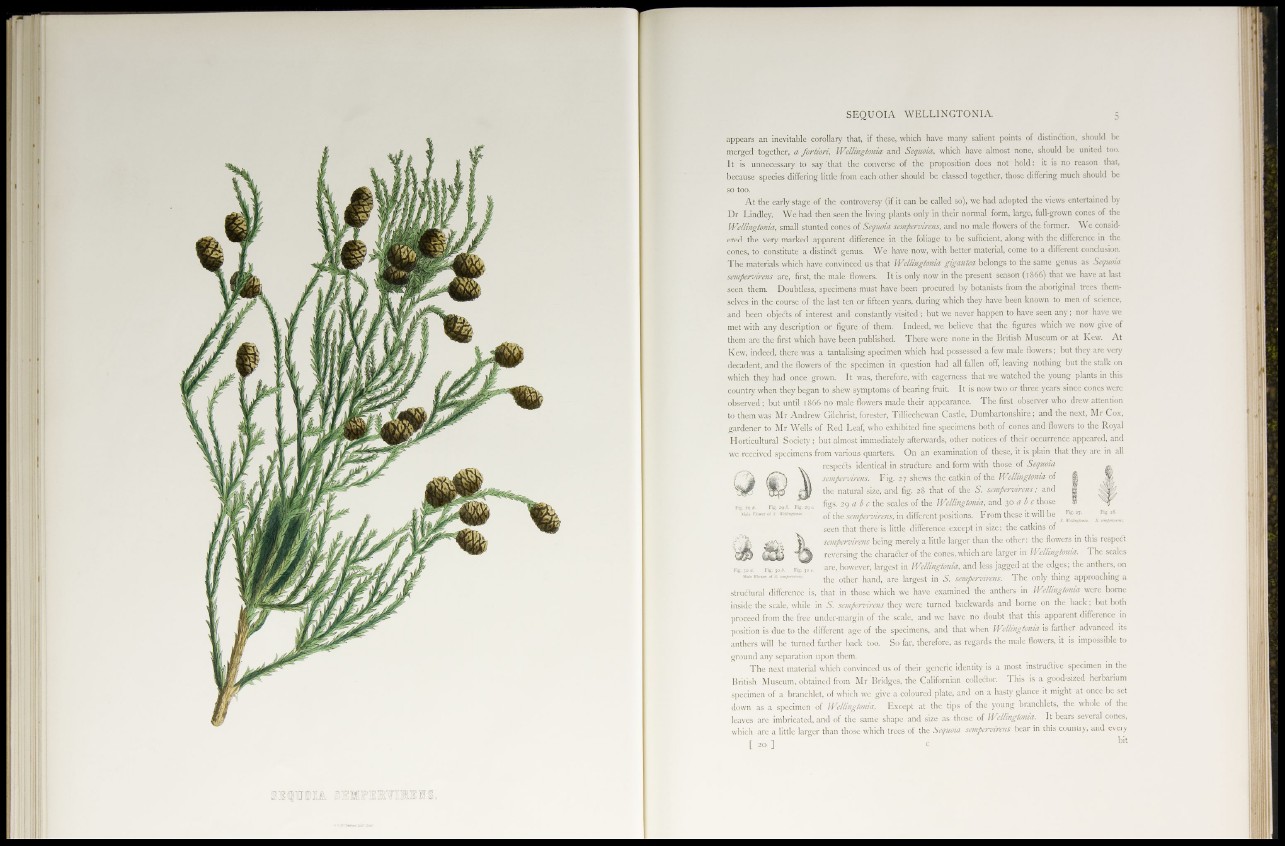

The next material which convinced us of their generic identity is a most instructive specimen in the

British Museum, obtained from Mr Bridges, the Californian colleftor. This is a good-sized herbarium

specimen of a branchlet, of which we give a coloured plate, and on a hasty glance it might at oncc be set

down as a specimen of Wellingtonia. Except at the tips of the young branchlets, the whole of the

leaves are imbricated, and of the same shape and size as those of Wellingtonia. It bears several cones,

which are a little larger than those which trees of the Sequoia sempervirens bear in this country, and e

[ 20 ]

bit