will be seen that each occupies a distinct territory, 1400 miles away from the other: the first in the western

Himmalayas; the second in Lebanon, Mount Taurus, and in the island of Cyprus; and the third in

the Mount Atlas Range in the north-east of Africa.

The existence of the Cedar in Cyprus has only recently been made known by Sir Joseph Hooker,

who, at the meeting of the Linnean Society, held on the 20th November 1879, exhibited a large branch

with male catkins and female cones, which had been sent to him from the mountains of that island by Sir

Samuel Baker. Its presence in Cyprus was previously entirely unsuspected. Sir Samuel said that the

monks of Trooditissa consider it to be the Chittim wood of Scripture. Sir Joseph, in commenting on the

specimen, stated that in general appearance, in the shortness of the leaves and the form of the cones, the

specimen resembled the Atlas more than the Lebanon form. The fact of the discovery of this station

for the Cedar suggests the possibility of its being found in some other unexplored localities. Plants have

been raised at Kew from the seeds sent home by Sir Samuel Baker, and at the present date (Dec. 1881)

the seedlings are strong and healthy.

Now, one thing is perfectly clear, and that is, that these three kinds of Cedar must all originally have

sprung from one common ancestor. That ancestor may have been the same as one of these, or it may

have been something different from either; but the close similarity of all three to each other prohibits the

supposition that the difference can have been material. How come these patches to be located at such

great distances from each other? Was there once a continuous forest of Cedars all the way from the

Himmalayas to Mount Atlas ? or, at least, was their range thus extensive, though not absolutely a

continuous forest ? or did they spread from one common centre, dropping a link here, and cut off by an

alteration of level there, so that we have not the remnants of three different quarters of one extensive camp,

but three camps left on two or more extensive journeys ?

The first and most important point to be ascertained is the date of the appearance of the Cedar in

geological time. Was it in existence previous to the Glacial epoch ? or was it a form which owed its

existence to the change of condition brought about by that epoch ? Was it a Miocene,

Fossil Remains. or a Post-Pliocene species ? One great difficulty, which we must lay our account with

in this inquiry, is the small chance there is of Cedar cones ever having been preserved

in a fossil state. As already said, the Cedar partakes of the nature of the Silver Firs, the

cone seldom falling entire from the tree. The scales as a rule, and sooner or later, drop off individually,

leaving the core of the cone standing erect like a branchlet (which homologically it is)—

consequently scales, leaves, and branches may be found; but a mature cone could rarely come within

the scope of fossil influence, except under exceptional circumstances. A Cedar cone would indeed

not be quite so hopeless a case as that of a Silver Fir, in which there are only a few weeks between

the ripening of the cone and its tumbling all to pieces; for the Cedar cone remains on the branches

for two or more years. Botanical collectors often find themselves baffled in collecting seeds of the

Silver Firs by this quality of their cones. If a week too late, the blows of their axe in cutting down

a tree to get the cones scatter them all to the winds. It is thus scarcely possible to conceive of any

means by which a ripe cone of a true Silver Fir can ever have been preserved in any fossil deposit.

The only time at which it could have been done is in the short interval between greenness and ripeness,

whilst it was still sufficiently green to hold together, and sufficiently dry and mature not to rot away.

A tree, growing on the bank of a river, at that stage might, by the falling in of the bank, be engulfed;

and in that case it is not impossible, although exceedingly improbable, that a Silver Fir cone might

be fossilised. As might be expected from all this, whilst fossil remains of cones of Pines and Spruces are

by no means rare, there are only two or three instances recorded of a fossil cone of a Silver Fir or Cedar

having been even supposed to be met with.*

• Schimper in his "Trait* de Palarontologie Vcgculc," lom. il p. 199, mentions the following fossil Cedars: (1) Calms Lccktntyi, Carruthers, lower grcensand, Slianklin,

Isteof Wig h^, C. Jienstedi; and (j) C. Cocmans, cretaceous rocks of 1 lainaull, llelgium. 11c describes C. Lakabyi and Cor,Mi as resembling the C. Dcodara rather than

Two

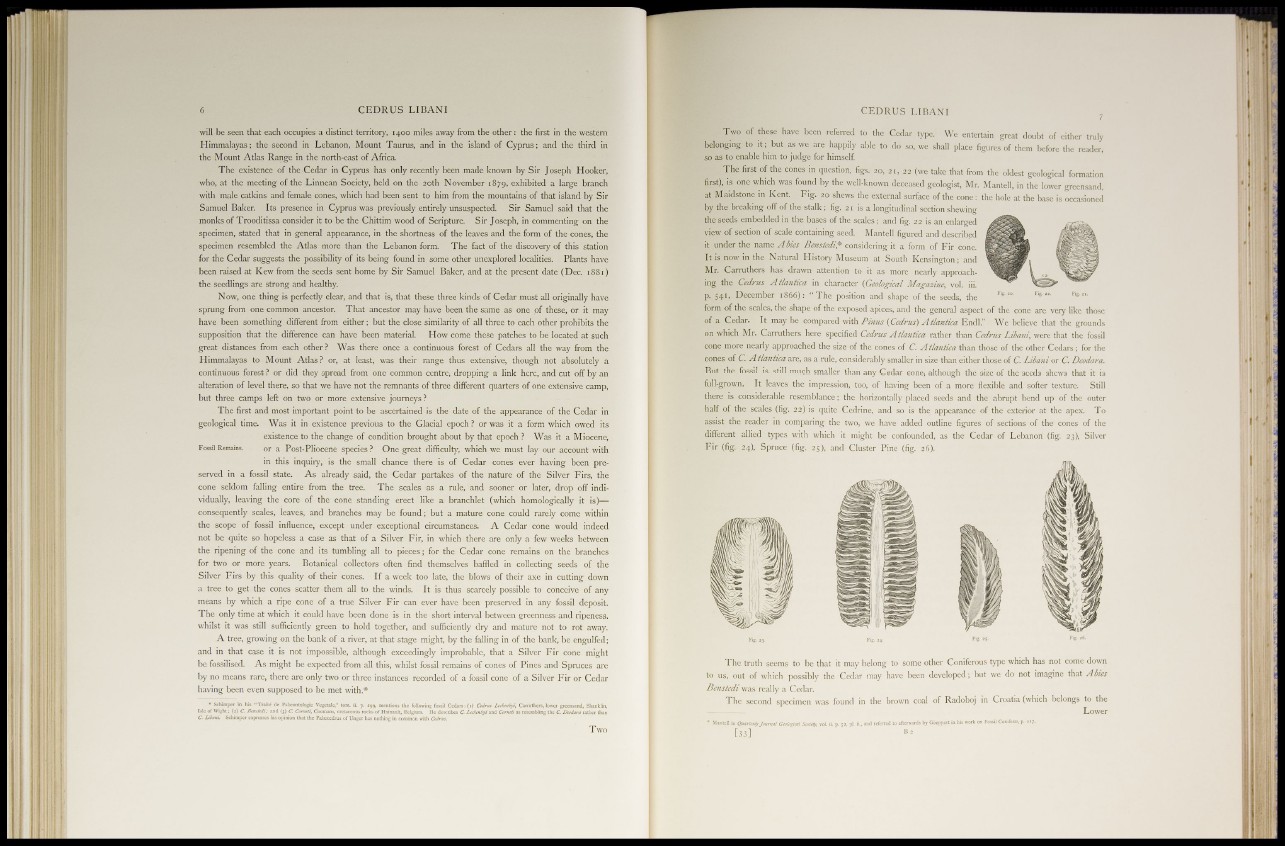

Two of these have been referred to the Cedar type. We entertain great doubt of cither truly

belonging to it; but as we are happily able to do so, we shall place figures of them before the reader,

so as to enable him to judge for himself.

The first of the cones in question, figs. 20, 21, 22 (we take that from the oldest geological formation

first), is one which was found by the well-known deceased geologist, Mr. Mantell, in the lower grcensand,

at Maidstone in Kent. Fig. 20 shews the external surface of the cone: the hole at the base is occasioned

by the breaking off of the stalk; fig. 21 is a longitudinal section shewing

the seeds embedded in the bases of the scales; and fig. 22 is an enlarged

view of section of scale containing seed. Mantell figured and described

it under the name Abies Benstedi,* considering it a form of Fir cone.

It is now in the Natural History Museum at South Kensington; and

Mr. Carruthers has drawn attention to it as more nearly approaching

the Cedrus Atlantica in character (Geological Magazine, vol. iii.

p. 541, December 1866): "The position and shape of the seeds, the Fi&"'

form of the scales, the shape of the exposed apices, and the general aspect of the cone are very like those

of a Cedar. It may be compared with Pinus {Cedrus) Atlantica Endl." We believe that the grounds

on which Mr. Carruthers here specified Cedrus Atlantica rather than Cedrus Libani, were that the fossil

cone more nearly approached the size of the cones of C. Atlantica than those of the other Cedars; for the

cones of C. Atlantica are, as a rule, considerably smaller in size than either those of C. Libani or C. Deodara.

But the fossil is still much smaller than any Cedar cone, although the size of the seeds shews that it is

full-grown. It leaves the impression, too, of having been of a more flexible and softer texture. Still

there is considerable resemblance; the horizontally placed seeds and the abrupt bend up of the outer

half of the scales (fig. 22) is quite Cedrine, and so is the appearance of the exterior at the apex. To

assist the reader in comparing the two, we have added outline figures of sections of the cones of the

different allied types with which it might be confounded, as the Cedar of Lebanon (fig. 23), Silver

Fir (fig. 24), Spruce (fig. 25), and Cluster Pine (fig. 26).

The truth seems to be that it may belong to some other Coniferous type which has not come down

to us, out of which possibly the Cedar may have been developed; but we do not imagine that Abies

Benstedi was really a Cedar.

The second specimen was found in the brown coal of Radoboj in Croatia (which belongs to the

Lower

" [ ''""""