timber could be conveyed; and in those days there was no sea route known from Syria to Persia, even

supposing them to be carried down to the Mediterranean and shipped there. The sea passage from the

mouth of the Indus to the Tigris, on the contrary, was an easy coasting voyage, in constant use; and we

know that the Deodar has been from time immemorial a main article of traffic on the former river. Of

the two, therefore, in the absence of anything leading to a contrary conclusion, there can be no doubt the

Deodar was most likely to be the timber used in the building of Nineveh; and Layard's beam, if it be of

Deodar Cedar, need not affect in the least our calculations as to the growth of the Cedar in Lebanon.

We shall now turn to the growth of the Cedar in our own country.

M. Loiseleur Deslongchamps and Mr. Loudon both took pains to contrast the growth of the wellknown

Cedar in the Jardin des Plantes, the first introduced into France (planted in 1734), with that of

two in the Botanic Garden at Chelsea, which are believed to be the oldest in Britain (planted in 1683);

but the comparison is marred by the Chelsea trees, during the first eighty-three years, having stood near

a pond, into which their roots extended, and from that cause made exceptionally rapid progress. Under

that stimulus, the trees, when eighty-three years old, exceeded 124 feet in girth at two feet from the ground,

while the Jardin des Plantes tree, when seventy-eight years old, had only made 94 feet; but after the pond

had been filled up, the Chelsea trees there did not add three feet to their circumference in sixty-eight

years, or nearly as long a time as they had previously taken to grow 124, the largest being only about

15 feet in 1834. It would also appear that two of them had had their lower branches cut in, to give light

to an orangery before which they had been placed ; and Miller tells us that they suffered so much in consequence,

that they were scarcely half so large as the two others which had been permitted to grow at

liberty. Which were the trees that had been so treated we do not know.

One, and only one, of the Chelsea trees still remains, but sections of the penultimate tree are preserved

in the British Museum, so far as its decayed state would allow, and from these specimens we have

taken the following details. A portion of the interior of the trunk, very much dry-rotted, but still holding

together, shewed the following rate of growth, viz.: the first 10 rings occupied 14 lines; the next 10, 22

lines; third, 17 lines; fourth, 14 lines; fifth, 13 lines; which gives an average rate of growth of 16 lines,

or an inch and a third in ten years.

Another specimen, which was next the bark, gives the following slower rate of growth: the first

10 inner rings occupied 21 lines; second 10, 11 lines; third, 5 lines; fourth, 9 lines; fifth, 7 lines; or,

taking the 30 outer rings only, an average growth of 7 lines per ten years, as opposed to 16.

A large limb furnishes an entire section, and gives the following growths on its widest side, the

growths on the other side being not so much developed, viz.: the first innermost 10 rings have a breadth

of 24 lines; second, 30 lines; third, 28 lines; fourth, 22 lines; fifth, 21 lines; sixth, i84 lines; seventh,

18 lines; eighth, 214 lines; ninth, 304 lines; tenth, 20 lines; eleventh, 18 lines; twelfth, 14 lines; thirteenth,

124 lines ; fourteenth, 9 lines; fifteenth, 5 lines ; making a total of 153 rings, having an average of

16 lines, as in the first specimen.

The dimensions of the tree in the Jardin des Plantes were, according to the data supplied to us by

M. Henri Vilmorin, as follow: in 1786, 4 feet 9 inches in girth, at 5 feet above the ground; in 1812,

5 feet 11 inches in girth, at 6 inches from the ground (Loiseleur Deslongchamps); in 1864, 10 feet 8

inches, at only 3 feet from the ground; in 1867, 11 feet 3 inches, at 5 feet from the ground. At the present

date (1882) it is 13 feet 2 inches, at 6 feet from the ground, and its height is 52 feet 9 inches.

These measurements do not quite correspond with those given by Loudon, which were as follows:—

Girth at the ground : 1786, 4 feet 9 inches; 1802, 7 feet 10 inches (Dutour in Nouv. Diet. d'Hist. Nat.,

iv. 449); 1818, 8 feet 8 inches; 1834, 1 0 feet 6 inches (Mirbel in Return paper to Loudon); and its height

80 feet, instead of only 46 feet 2 inches as at present.

We prefer the measurements of M. Vilmorin as the more accurate, seeing that they accord throughout

better with their present state, as to which there can be no dispute.

But

But the impossibility of placing plants growing in distant localities, under anything like the same cir

cumstances, renders all such comparisons of little value. All that we can obtain from them with certainty

is additional proof of what is sufficiently well known already, that, under favourable circumstances, the

Cedar grows with as much rapidity as any other conifer, and under unfavourable circumstances, as slowly,

perhaps more slowly. The favourable circumstances seem to be a rather moist and mild climate, and the

unfavourable conditions, a bleak one, with a short and cold summer.

The average rate of growth in this country seems to be about a foot in length each year, until it

reaches fifty years of age, when the rate gradually decreases.

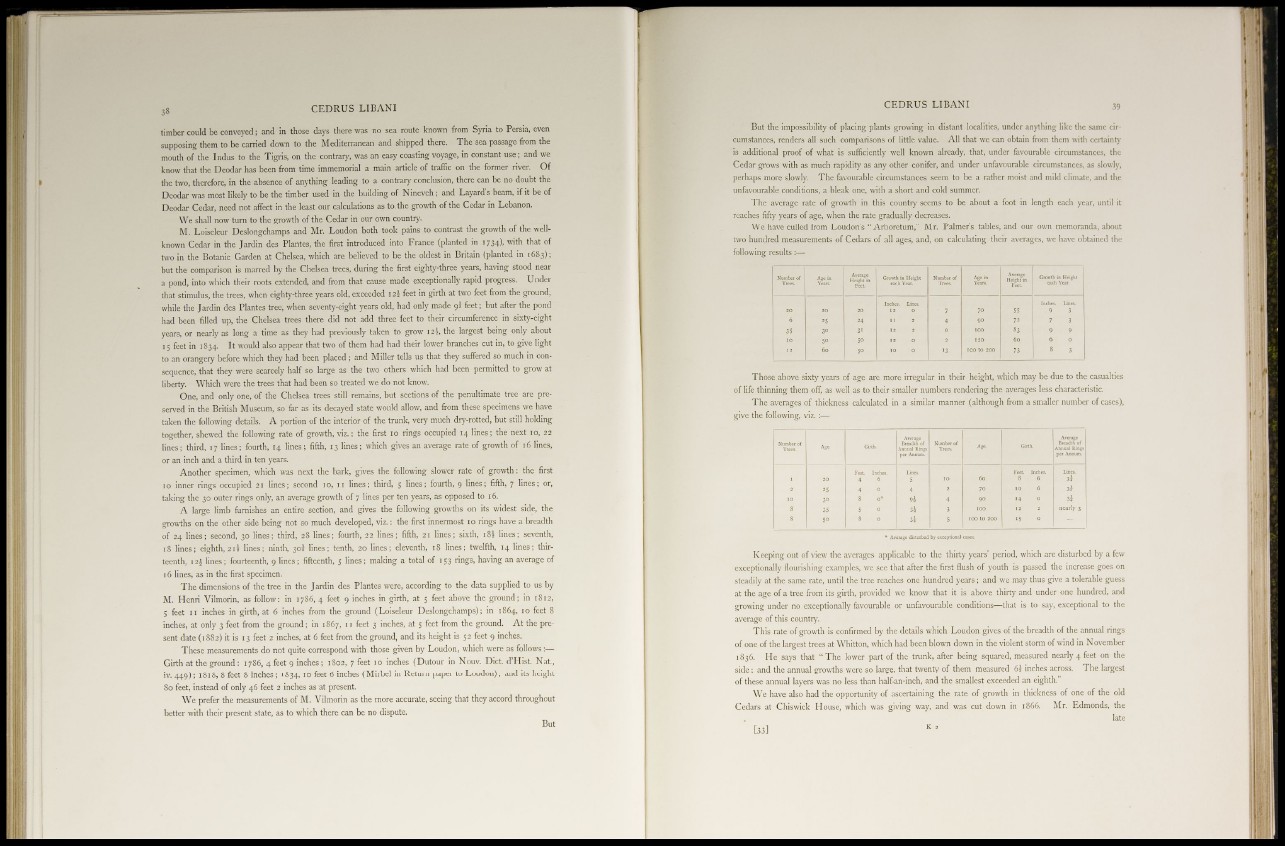

We have culled from Loudon's "Arboretum," Mr. Palmer's tables, and our own memoranda, about

two hundred measurements of Cedars of all ages, and, on calculating their averages, we have obtained the

following results:—

Those above sixty years of age are more irregular in their height, which may be due to the casualties

of life thinning them off, as well as to their smaller numbers rendering the averages less characteristic.

The averages of thickness calculated in a similar manner (although from a smaller number of cases),

give the following, viz. :—

Keeping out of view the averages applicable to the thirty years' period, which are disturbed by a few

exceptionally flourishing examples, we see that after the first flush of youth is passed the increase goes on

steadily at the same rate, until the tree reaches one hundred years ; and we may thus give a tolerable guess

at the age of a tree from its girth, provided we know that it is above thirty and under one hundred, and

growing under no exceptionally favourable or unfavourable conditions—that is to say, exceptional to the

average of this country.

This rate of growth is confirmed by the details which Loudon gives of the breadth of the annual rings

of one of the largest trees at Whitton, which had been blown down in the violent storm of wind in November

1836. He says that "The lower part of the trunk, after being squared, measured nearly 4 feet on the

side ; and the annual growths were so large, that twenty of them measured 64 inches across. The largest

of these annual layers was no less than half-an-inch, and the smallest exceeded an eighth."

We have also had the opportunity of ascertaining the rate of growth in thickness of one of the old

Cedars at Chiswick House, which was giving way, and was cut down in 1866. Mr. Edmonds, the

late