brings testimony in support of it:—" The Maronites say that no sooner do the snows begin to fall than

these Cedars, whose boughs are now all so equal in extent that they appear to have been shorn, never fail

to change their figure. The branches, which before spread themselves, rise insensibly, gathering together,

it may be said, and turn their points upwards towards heaven, forming altogether a pyramid. It is nature,

they say, that inspires this movement, and makes them take a new shape, without which these trees could

never sustain the immense weight of snow remaining for so long a time." * It is to this fabled (it is unnecessary

to add wholly imaginary) property that Southey alludes in " Thalaba "—

It was a Cedar tree

That woke him from the deadly drowsiness;

lis broad round spreading branches, when they fell,

Defied the baffled storm."

Lambert records, as a peculiarity of the Cedar, that if a branch of the Cedar is cut off, " the part

remaining in the trunk gradually loosens itself, and assumes a round form resembling a potato; and if the

bark covering it be struck smartly with a hammer, the knot leaps out." Loudon quotes the passage,

adding, " This fact, Mr. Lambert states, was communicated to him by Sir Joseph Banks; but he adds

that he had tried the experiment himself." If he had tried the experiment on an oak, or any other tree, he

would have obtained the same results; indeed, the knot when ready leaps out under the mere influence of

the growth of the tree and warm weather without being struck at all.

Culture.—Loudon says that in whatever soil or situation the Larch grows, there the Cedar will

probably also thrive. This is not confirmed by the experience which we have had since he wrote. The

Larch usually thrives throughout Scotland (the Larch disease is an exceptional complaint, the causes of

which are not yet determined), but in many parts of it the Cedar does not thrive, or, we should say, does

not grow so rapidly as it does in England. The climate, especially north of the Forth, has too little

summer heat and too much winter cold, not for its existence, but for its rapid development. As regards

the winter cold, it probably comes nearer the condition of its natural climate, and the slow-grown Scotch

specimens, if we had patience to wait for them, may be nearer the Lebanon-grown trees in character as well

as rate of growth than the English specimens.

Mr. Palmer's tables shew that, during the winter of i860, out of sixty-one places in England it was

uninjured at thirty-eight, slightly injured at thirteen, much injured at six, and killed at four; in Scotland,

out of eighteen places, all escaped, except at seven, at one of which (Hamilton Palace) some old trees were

killed; at the rest the injury done was not great; and in Ireland reports were had from only two places,

and at both the trees were uninjured.

The worst injury done was at Hamilton Palace, and at Short Grove in Essex, at both of which it

was old trees that suffered. At Short Grove there were six trees at the bottom of the park (the lowest

ground) about 100 years old, from 40 to 60 feet high, and with stems from 9 to 12 feet in circumfcrence;

and five others about twenty years old, and from 12 to 15 feet high, all killed ; and twenty-five trees about

100 years old, and from 50 to 60 feet high, so much injured, that recovery was impossible. Besides these

there were in the pleasure-grounds, near the house, four trees about 100 years old, and from 50 to 60 feet

high, which lost the ends of the branches, and were much injured, though not so severely as those in the

low grounds; and on the highest ground there were sixteen trees about 100 years old, and from 50 to 60

feet high, which were slightly injured.

In some of the places in Mr. Palmer's tables where the trees are reported as injured, the young trees

were left leafless and nearly killed, and the old trees much browned, and the shoots of two or three years

old

old killed, and in many cases they afterwards lost large branches. In some cases the trees struggled

through the winter of 1860-61, only to succumb to the much less severe one of 1863—their stamina having

been too much injured by the former to sustain the feebler attack of the latter.

The Cedar seems not to stand the sea-breezes well. In Mr. Palmer's reports there are constant

memoranda to that effect. Neither does it bear late spring frosts.

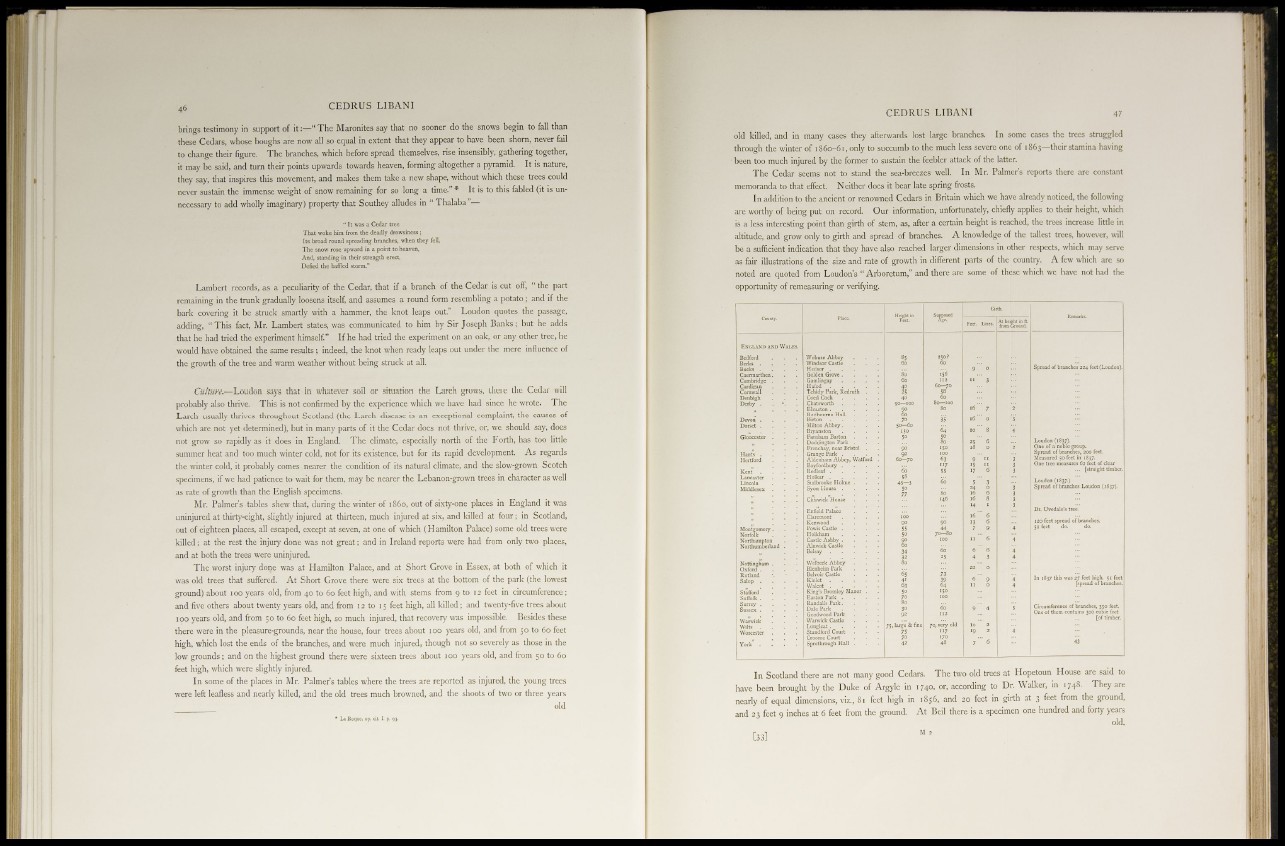

In addition to the ancient or renowned Cedars in Britain which we have already noticed, the following

are worthy of being put on record. Our information, unfortunately, chiefly applies to their height, which

is a less interesting point than girth of stem, as, after a certain height is reached, the trees increase little in

altitude, and grow only to girth and spread of branches. A knowledge of the tallest trees, however, will

be a sufficient indication that they have also reached larger dimensions in other respects, which may serve

as fair illustrations of the size and rate of growth in different parts of the country. A few which arc so

noted are quoted from Loudon's " Arboretum," and there are some of these which we have not had the

opportunity of remeasuring or verifying.

In Scotland there are not many good Cedars. The two old trees at Hopetoun House are said to

have been brought by the Duke of Argyle in 1740, or, according to Dr. Walker, in 1748. They are

nearly of equal dimensions, viz, 81 feet high in 1856, and 20 feet in girth at 3 feet from the ground,

and 23 feet 9 inches at 6 feet from the ground. At Beil there is a specimen one hundred and forty years

old.