the seventh century of our era. This' statement, says

M. Abel-Rémusat, confirms the accounts delivered by the

Chinese, and overturns all the theoretical schemes which

learned men of Europe have set up as to the origin of arts

and sciences and the vast antiquity of literature iintthe

mountains of Tibet and Tangut.# Chinese historians report

that the Kiang, who were the real Tibetan, race,-were

a very barbarous people till about the sixth and. seventh

centuries of our era. At this time the Kiang, called also*

the Ti, had the same religion which prevailed in China

before the introduction of Buddhism.^ They celebrated

a triennial sacrifice of oxen and sheep to the Heavens»,; and

they spoke a language resembling the Chinese in the centre

of the empire.

The Tibetans name their own country Bod or Bod^bha,

and themselves Bod-gjij: Their language is generally con^

sidered as one of monosyllabic structure, bdt» do this,

according to M. Abel-Rémusat, there are many exceptions.

It has many words in common with the Chinese,! and Klaproth

has pointed out resemblances with th&Jfurkish and

other Tartarian languages. The words as written,

a great number of consonants, many of which are not pronounced

in the refined dialect of H’Lassa, through imitation

of Chinese softness; but, according to the missionaries, they

are still heard in the ruder idiom of thé mountains of

Kombo.§ But the idiom of Tibet was never thoroughly

* Ibid. t Recherches sur les Languës Tartares,

tKliproth, Asia Polyglotta. Hence the name Bhotfyahs, by which thé

people of Tibet and Bhutan are known in India.

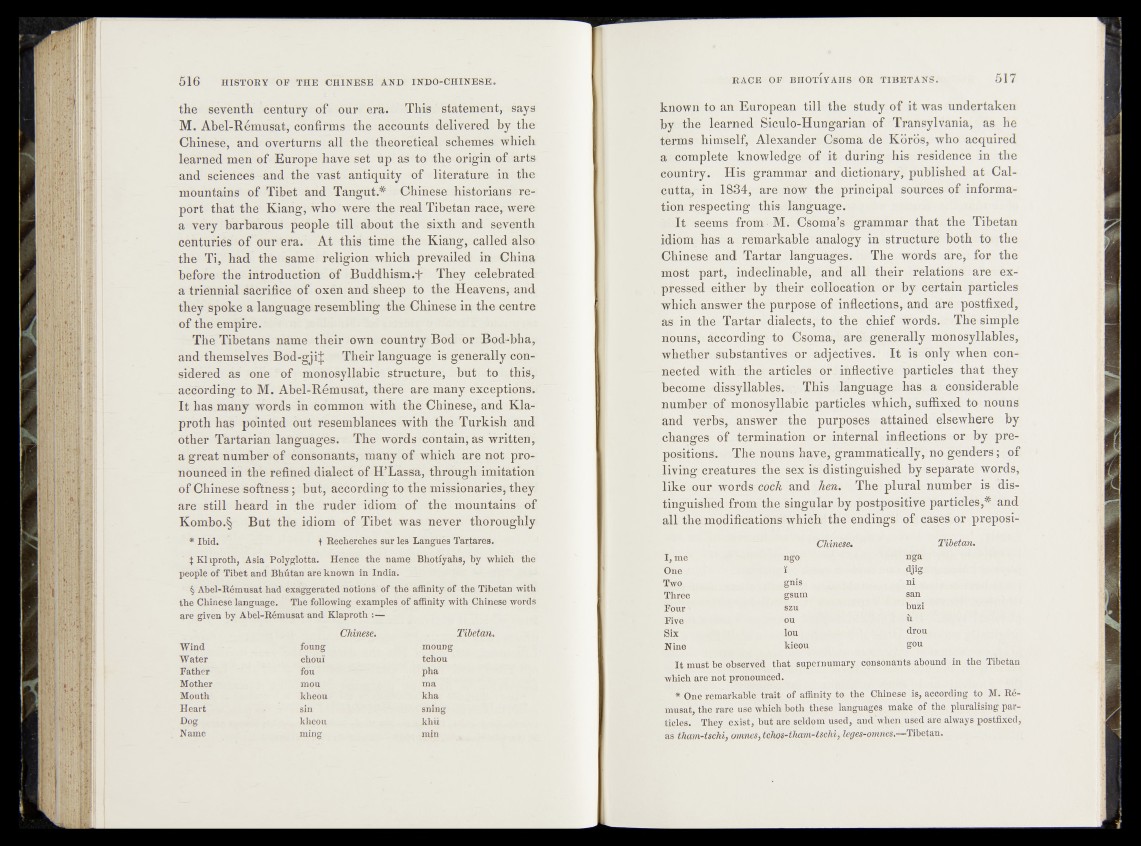

§ Abel-Rémusat had exaggerated notions of thé affinity of the Tibetan with

the Chinese language. The following examples of affinity with Chinese words

ere given by Abel-Rémusat and Klaproth :—

Chinese. Tibetan.

Wind foung moung

Water choux tchou

Father fou pha

Mother mou ma

Mouth kheou kha

Heart sin suing

Dog kheou khii

Name ming min

known to an European till the study of it was undertaken

by the learned Siculo-Hungarian of Transylvania, as he

terms hi msel^jAlexander Csoma de Koras, who acquired

a complete knowledge of it during his residence in the

country. His grammar and dictionary, published at Calcutta,

in 1884, are now the principal sources of informa-»

tion rçspectingr this language.

" It seems from^M. Csoma’si grammar that the Tibetan

idiom has a remarkable analogy ml structure both to the

Chinese and Tartar languages.v. The words are, for the

most part, indeclinable, and all their relations are expressed

either by their collocation or by certain particles

which answer the purpose of inflections, and are postfixed,

as f in the Tartar dialects, , to the chief words. The simple

nouns, according to Csoma* are generally monosyllables,

whether substantives.or adjectives.■ It is-only when connected,

wjth. the. articles or inflective particles that they

become 'dissyllables.;- /. This language has a considerable

number;of monosyllabic particles which, suffixed to nouns

and verbs, answer the purposes attained elsewhere by

changes of termination or. internal inflections or by prepositions.

The nouns have, grammatically, no genders ; of

living creatures the sex is distinguished by separate words,

like our words cock and hen. The plural number is distinguished

from the singular by postpositive particles,* and

all the modifications which the endingà of cases or preposi-

Chinese. Tibetan.

I, me ngo nga

One ï - f $ig*i

Two gnis ni ;

Three . gsum san

Four ® szu buzi

Five :/ ou ’ • -- ù +

Six Ion . drou

Nine kieou 1 goa

It must be observed that supernumary consonants abound in the Tibetan

which are not pronounced.

* One remarkable trait of affinity to the Chinese is, according to M. R6-

musat, the rare use which both these languages make of the pluralising particles.

They exist, but are seldom used, and'when used are always postfixed,

as tham-tschi, omnes, teJios-tham-tschi, leges~omnes.-—Tibetan.