present undertaking,* and I shall merely remark, with

respect- to it, that the*.Resemblances in particular grammatical

elements, as in the pronouns especially, and also

those which may be pointed out in' radical woi$s,—of .these

a short specimen has already been given from Scherer,

which has been greatly extended by Klaproth,—between

even the most western European languages and the Mongolian

and Mandschd, spoken in the extreme east of Asia,

are certainly too strong and decided to be attributed .to1

mere accidental coincideneei while, on the other hand&Sj|.

is impossible to account for these phenomena by Referring

them to occasional intercourse, a thing which cannot bp

imagined between nations so widely remote from, each other.

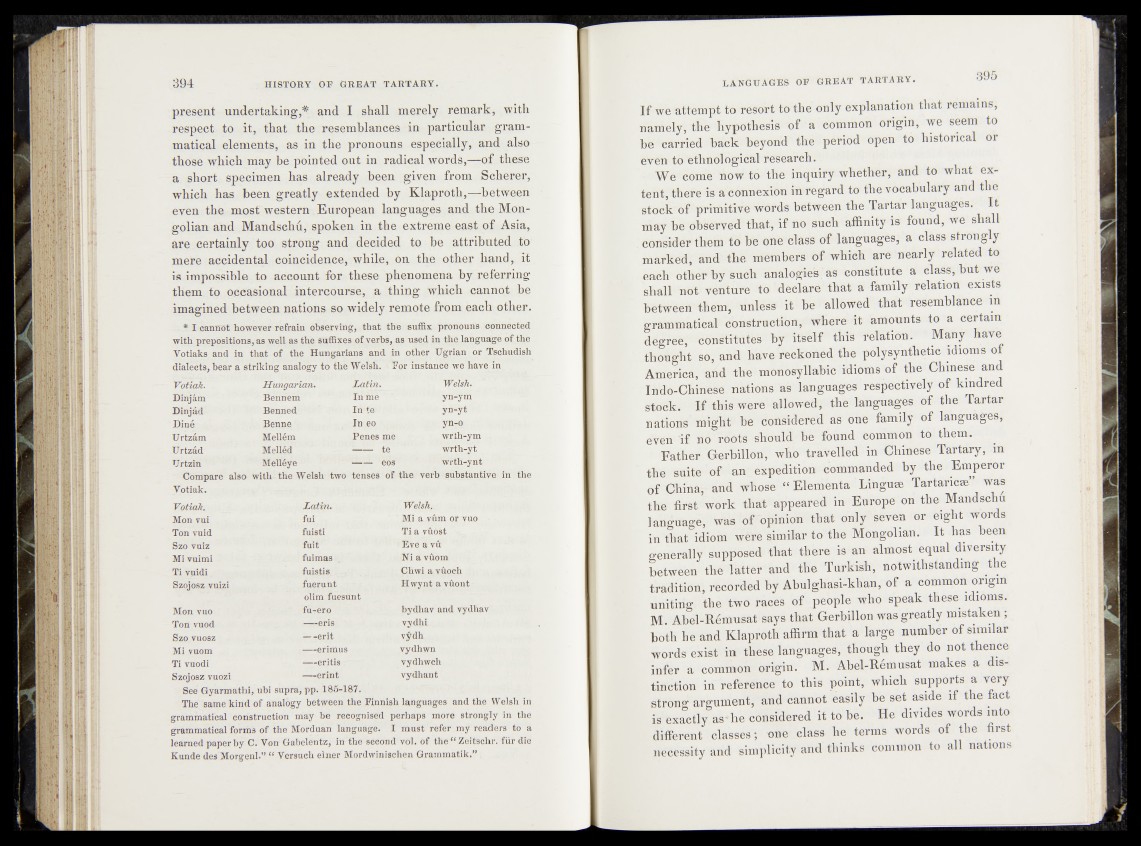

* I cannot however refrain observing, that the suffix pronoun's connected

with prepiositions, as well as the suffixes of verbs, as used in ^ e language of the

Votiaks and in that of the Hungarians and in other Ugrjan ^or Tschudish

dialects, bear a striking analogy to the Welsfi. instance we have fn^ v

Votiak. Hungarian. Latin. Welsh. '

Dinjâm ' Benném ' l§Mg | yiî-fm ‘ ■'

Dinjàd Benned In-te yn-yt *

3>lné .. Benne In.eo .

Urtzâm Mellém Penes me wx tié-ym ,,

Urtzâd Mellêd I----- wrth-yt

TJrtzîn MeÏÏéÿe P wi-th-ynt

Compare also with the Welsh two

tenses of the*> vèrb ^substantiv®

Votiak.

Votiak. Latin. Welsh..

Mon vuf fui - Mi A-yûm or vuo. •

Ton vuid fuistl Ti a vûôst \

Szo vuiz fuit ?Êve a vû

Mi vuimi fui mas 4fi a vûom

Ti vuidi. fuistis. I» Chvp a vûoeh

Szojosz vuizi fuerunt

olim fuesunt

Hwynt a vûoufc -

Mon vuo furèro 1 bydhav and vydhav’

Ton vnod —-eris vydhi

Szo vuosz —-erit vÿdh.

Mi vuom . -— erimus vydhwn

Ti fuodl — eritis vydhwch

Szojosz vuozi — erint vydhant

See Gyarcnathi> uhi supra, pp. 185-187.

The same kind of analogy between the Finnish languages and the Welsh in

grammatical construction may be recognised perhaps more strongly in the

grammatical forms of the Morduan language. I must refer my readers to a

learned paper by C. Von- Gabeldbtz/ in the second vol. Of thef< Zeitscht. für die

Kunde des Morgenl.”-“ Yersuch einer Mordwinischen Grammatik.";

If to-resort to the only explanation that remains,

namely, the h y p oA te ^ o f‘a common origin, we seem to

be carried back beyMH thé period open to historical or

eveîr to ’ethnological research. ‘

Wètfêtó^now tb^tfté' -inquiry whether,' and to what 'esf-

tent, there is abónnexibn irt-regard to the vocabulary and the

stock o f primitive words between the Tartar languages. It

may %b:öbserved that, if no sù-éh affinity is found, we shall

consider them to he onekdass of languages, a class strongly

marked, and the members of which are nearly related to

each"-atïèHsy such analïd^èkf-as constitute a class, but we

shâM not ve#t‘u¥e to déclaré'that a family relation exists

between them, ^ n l é ^ it be allowed that resemblance m

grammatical construction, whereat amounts to a certain

degree,--cöiistitute^by itself this relation!- Many have,

thoöght so, and have reckoned the polysynthetic idioms of

America, ^bd the monosyllabic idioms of the Chinese and

Indo-Chinese nations as languages respectively of kindred

stock. If this were allowed, the languages of the Tartar

nations might he considéféd as one family of languages,

even if no roots should be found common to: them;

Fathë# Gerhillotfi who travelled in' Chinese Tartary, m

the suite of an expedition -commanded by the Emperor

éf Chinar and whose-' “ Elemënta Linguæ Tartaricæ” was

the first work that appeared in Europe on the-Mandschu

language, was of opinion that only seven or bight words

in that idiom wëfiè sîhiilar to the Mongolian. It chas keen

generally supposed that there is an almost equal diversity

between the latter and the Turkish, notwithstanding the

tradition, recorded by Abulghasi-khan, of a common origin

uniting the two races of people who speak these idioms.

M. Abèl-Rémusat says that Gerbillon was greatly mistaken ;

both he and Klaproth affirm that a large number of similar

words exist in these languages, though they do not thence

. infer a common origin. M. Abel-Rémusat makes a distinction

in reference to this point, which supports a very

strong argument, and cannot easily he set aside if the fact

is exactly as*he considered it to be. He divides words into

different classes; one class be terms words of the first

necessity and simplicity and thinks common to all nations