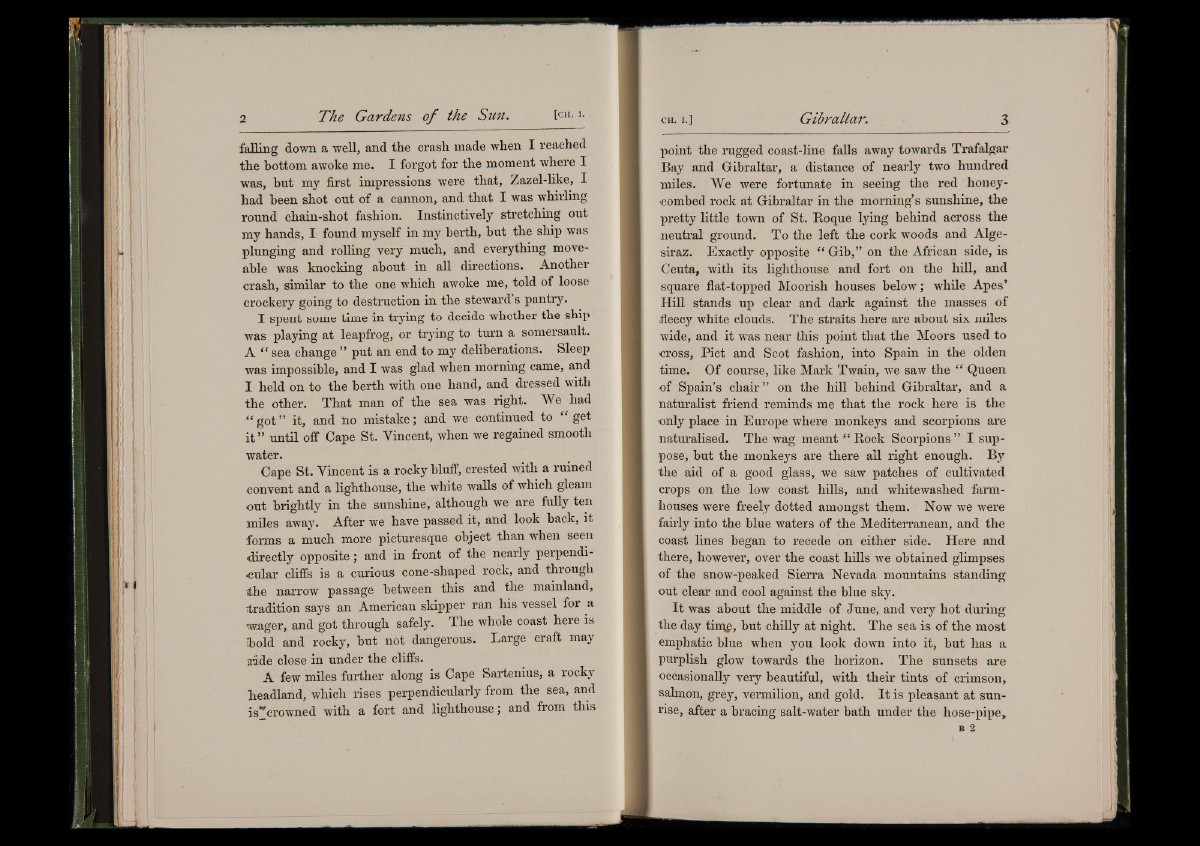

falling down a well, and the crash made when I reached

the bottom awoke me. I forgot for the moment where I

was, hut my first impressions were that, Zazel-like, I

had been shot out of a cannon, and that I was whirling

round chain-shot fashion. Instinctively stretching out

my hands, I found myself in my berth, but the ship was

plunging and rolling very much, and everything move-

able was knocking about in all directions. Another

crash, similar to the one which awoke me, told of loose

crockery going to destruction in the steward s pantry.

I spent some time in tiying to decide whether the ship

was playing at leapfrog, or trying to turn a somersault.

A “ sea change ” put an end to my deliberations. Sleep

was impossible, and I was glad when morning came, and

I held on to the berth with one hand, and dressed with

the other. That man of the sea was right. We had

“ got ” it, and Ho mistake; and we continued to “ get

i t ” until off Cape St. Yincent, when we regained smooth

water.

Cape St. Yincent is a rocky bluff, crested with a ruined

convent and a lighthouse, the white walls of which gleam

out brightly in the sunshine, although we are fully ten

miles away. After we have passed it, and look back, it

forms a much more picturesque object than when seen

directly opposite; and in front of the nearly perpendicular

cliffs is a curious cone-shaped rock, and through

the narrow passage between this and the mainland,

(tradition says an American skipper ran his vessel for a

mager, and got through safely. The whole coast here is

Ibold and rocky, but not dangerous. Large craft may

aide close in under the cliffs.

A few miles further along is Cape Sartenius, a rocky

headland, which rises perpendicularly from the sea, and

is'rcrowned with a fort and lighthouse; and from this

point the rugged coast-line falls away towards Trafalgar

Bay and Gibraltar, a distance of nearly two hundred

miles. We were fortunate in seeing the red honeycombed

rock at Gibraltar in the morning’s sunshine, the

pretty little town of St. Roque lying behind across the

neutral ground. To the left the cork woods and Alge-

siraz. Exactly opposite “ Gib,” on the African side, is

Ceuta, with its lighthouse and fort on the hill, and

square flat-topped Moorish houses below; while Apes’

Hill stands up clear and dark against the masses of

fleecy white clouds. The straits here are about six miles

wide, and it was near this point that the Moors used to

cross, Piet and Scot fashion, into Spain in the olden

time. Of course, like Mark Twain, we saw the “ Queen

of Spain’s chair” on the hill behind Gibraltar, and a

naturalist friend reminds me that the rock here is the

•only place in Europe where monkeys and scorpions are

naturalised. The wag meant “ Rock Scorpions ” I suppose,

but the monkeys are there all right enough. By

the aid of a good glass, we saw patches of cultivated

crops on the low coast hills, and whitewashed farmhouses

were freely dotted amongst them. Now we were

fairly into the blue waters of the Mediterranean, and the

coast lines began to recede on either side. Here and

there, however, over the coast hills we obtained glimpses

of the snow-peaked Sierra Nevada mountains standing

out clear and cool against the blue sky.

It was about the middle of June, and very hot during

the day tiny?, but chilly at night. The sea is of the most

emphatic blue when you look down into it, but has a

purplish glow towards the horizon. The sunsets are

occasionally very beautiful, with their tints of crimson,

salmon, grey, vermilion, and gold. It is pleasant at sunrise,

after a bracing salt-water bath under the hose-pipe,