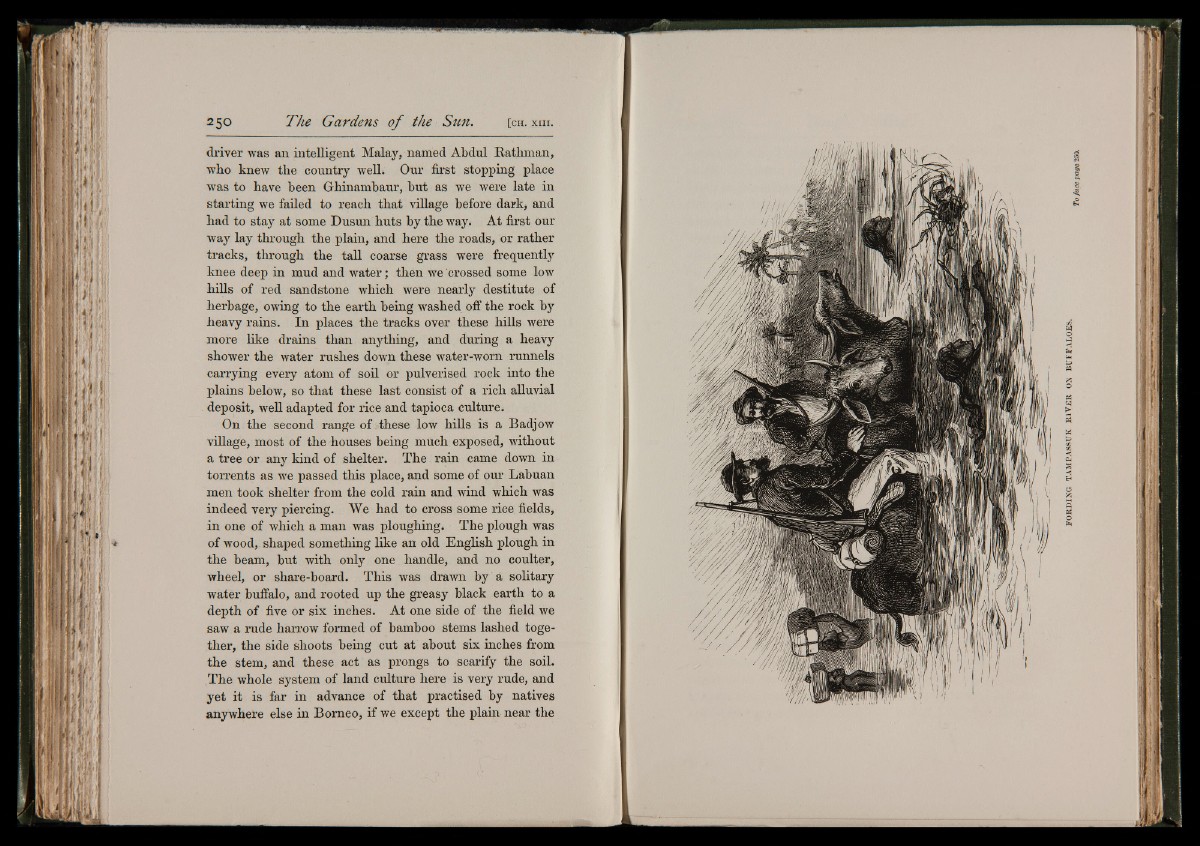

driver was an intelligent Malay, named Abdul Rathman,

who knew the country well. Our first stopping place

was to have been Ghinambaur, but as we were late in

starting we failed to reach that village before dark, and

had to stay at some Dusun huts by the way. At first our

way lay through the plain, and here the roads, or rather

tracks, through the tall coarse grass were frequently

knee deep in mud and water; then we crossed some low

hills of red sandstone which were nearly destitute of

herbage, owing to the earth being washed off the rock by

heavy rains. In places the tracks over these hills were

more like drains than anything, and during a heavy

shower the water rushes down these water-worn runnels

carrying every atom of soil or pulverised rock into the

plains below, so that these last consist of a rich alluvial

deposit, well adapted for rice and tapioca culture.

On the second range of these low hills is a Badjow

village, most of the houses being much exposed, without

a tree or any kind of shelter. The rain came down in

torrents as we passed this place, and some of our Labuan

men took shelter from the cold rain and wind which was

indeed very piercing. We had to cross some rice fields,

in one of which a man was ploughing. The plough was

of wood, shaped something like an old English plough in

the beam, but with only one handle, and no coulter,

wheel, or share-board. This was drawn by a solitary

water buffalo, and rooted up the greasy black earth to a

depth of five or six inches. At one side of the field we

saw a rude harrow formed of bamboo stems lashed together,

the side shoots being cut at about six inches from

the stem, and these act as prongs to scarify the soil.

The whole system of land culture here is very rude, and

yet it is far in advance of that practised by natives

anywhere else in Borneo, if we except the plain near the