i cannot speak tea highly of' the hospitable and obliging disposition

of the proprietors of Porto Santo, who mà,y be compared

with our smaller Welch farmers. ' I never pursued my rambles

without being entreated'to turn1 a little out of my way to drink a

cup of their best wine, which was no small temptation, being the

pure juice of the richest grapes, without even a dash of spirit; and

before we quitted the island, one sent a dozen of this wine,

another, two dozen, a third, a fine turkey; agreeably reminding

me of the African custom of “ making a dash” to a stranger: their

horses, their servants, all were at my service, and I was obliged to

start by daylight, to avoid the necessity of accepting the use of the

former (not suiting my route amongst the cliffs and peaks), four

of which were sent for me in one morning. Instead of that

impertinent curiosity, accompanied by a broad laugh or contemptuous

sneer, which a traveller too often meets with from the class

immediately above the peasantry in* Madeira, who ridicule every

thing they do not understand, and always take fresh pride to

themselves on discovering fresh proofs of their ignorance ; instead

of this feeling, which is made more striking by the polished

manners of the higher orders, and by the respectful civility of the

peasantry, the same class of men in Porto Santo, although prompted

by a more laudable curiosity, never ventured to approach an

instrument unless I invited them to do so, and then modestly

sought some explanation of its use and object.

I had great difficulty in excusing myself from breakfasting and,

dining with the governor, on each of the three days of my stay,

which I made the most of, by quitting the town at sunrise, and

never returning until dark. Every evening, however, after I had

deposited my spoils in the embryo shop of my friend Battista, and

inquired as to the sales of the day, and the rising prospects of the

new establishment, we both left off work, washed our hands, and

adjourned to the soirée of the governor’s lady,* who dispensed

excellait green tea, new cakes, and old packs of caids every

evening ; with the view, as she archly termed it, of civilizing the

officers of the militia a little, amongst whom the serjeants were

included. She was not handsome, but of very ladylike and

agreeable manners, and full of entertaining conversation. Having

groped our way to the government house, we were quitted at the

portal by a small mob of the humbler friends and acquaintances

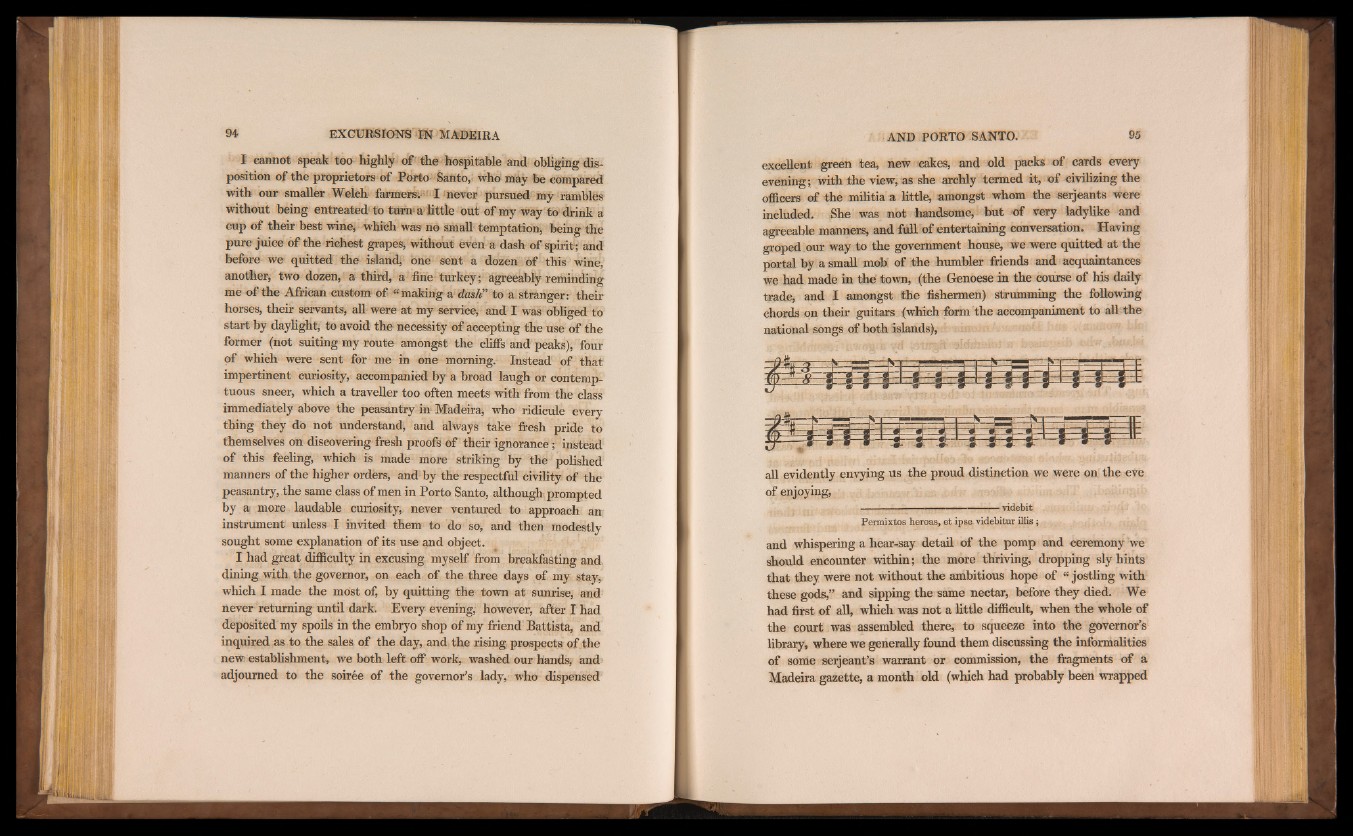

we had made in the town, (the Genoese in the course of his daily

trade, and I amongst the fishermen) strumming the following

chords on their guitars (which form the accompaniment to all the

national songs of both islands),

all evidently envying us the proud distinction we were on the eve

of enjoying,

videbit

Permixtos heroas, et ipse videbitur illis;

and whispering a hearsay detail of the pomp and ceremony we

should encounter within; the more thriving, dropping sly hints

that they were not without the ambitious hope of “ jostling with

these gods,” and sipping the same nectar, before they died. We

had first of all, which was not a little difficult, when the whole of

the court was assembled there, to squeeze into the governor’s

library, where we generally found them discussing the informalities

of some sejjeant’s warrant or commission, the fragments of a

Madeira gazette, a month old (which had probably been wrapped