to these places of shelter there were the photographic

dark tent, five feet six square, the kitchen, and the

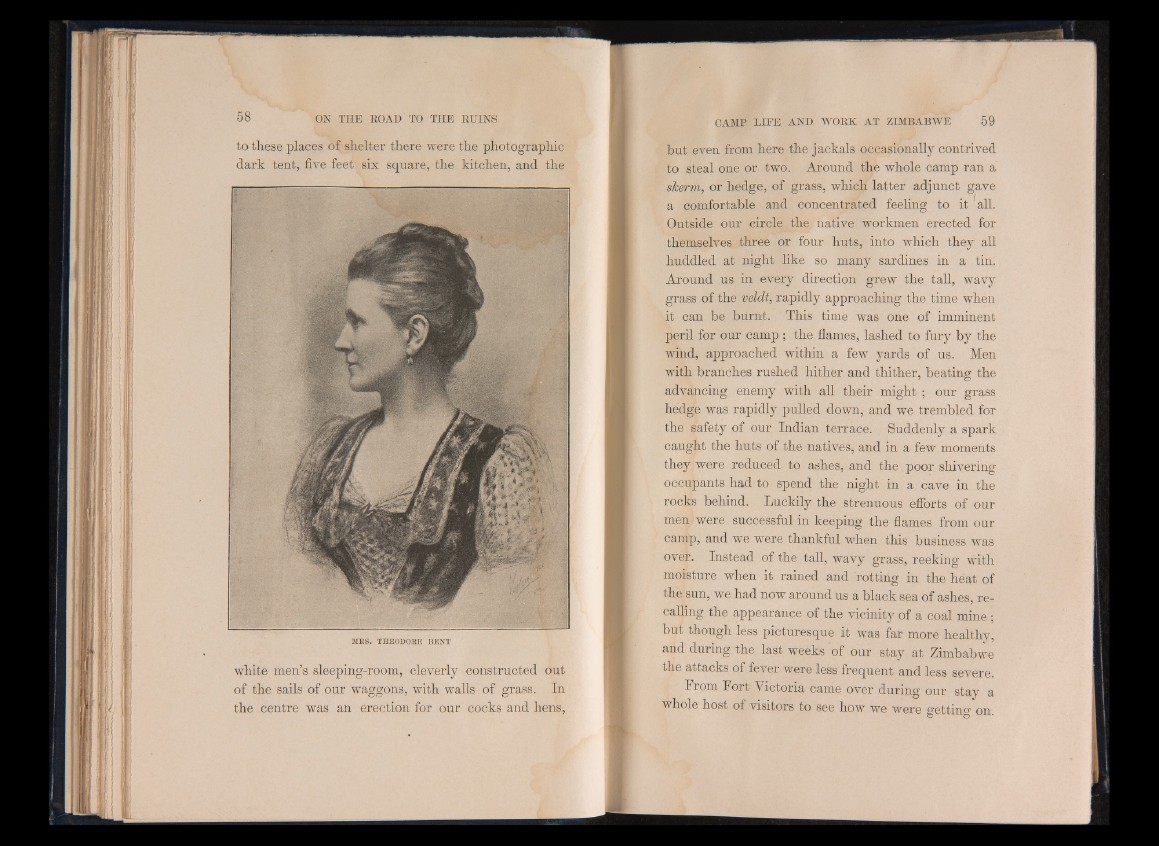

MRS. THEODORE BENT

white men’s sleeping-room, cleverly constructed out

of the sails of our waggons, with walls of grass. In

the centre was an erection for our cocks and hens,

but even from here the jackals occasionally contrived

to steal one or two. Around the whole camp ran a

skerm, or hedge, of grass, which latter adjunct gave

a comfortable and concentrated feeling to it all.

Outside our circle the native workmen erected for

themselves three or four huts, into which they all

huddled at night like so many sardines in a tin.

Around us in every direction grew the tall, wavy

grass of the veldt, rapidly approaching the time when

it can be burnt. This time was one of imminent

peril for our camp ; the flames, lashed to fury by the

wind, approached within a few yards of us. Men

with branches rushed hither and thither, beating the

advancing enemy with all their might ; our grass

hedge was rapidly pulled down, and we trembled for

the safety of our Indian terrace. Suddenly a spark

caught the huts of the natives, and in a few moments

they were reduced to ashes, and the poor shivering

occupants had to spend the night in a cave in the

rocks behind. Luckily the strenuous efforts of our

men were successful in keeping the flames from our

camp, and we were thankful when this business was

over. Instead of the tall, wavy grass, reeking with

moisture when it rained and rotting in the heat of

the sun, we had now around us a black sea of ashes, recalling

the appearance of the vicinity of a coal mine ;

but though less picturesque it was far more healthy,

and during the last weeks of our stay at Zimbabwe

the attacks of fever were less frequent and less severe.

From Fort Victoria came over during our stay a

whole host of visitors to see how we were fretting- on o o