the roadside as we passed along we saw many acres

under cultivation for the produce of sweet potatoes,

beans, and the ground or monkey nut (Arachis). They

make long neat furrows with their hoes beneath the

trees, the shade of which is necessary for their crops.

They are an essentially industrious race, far more so

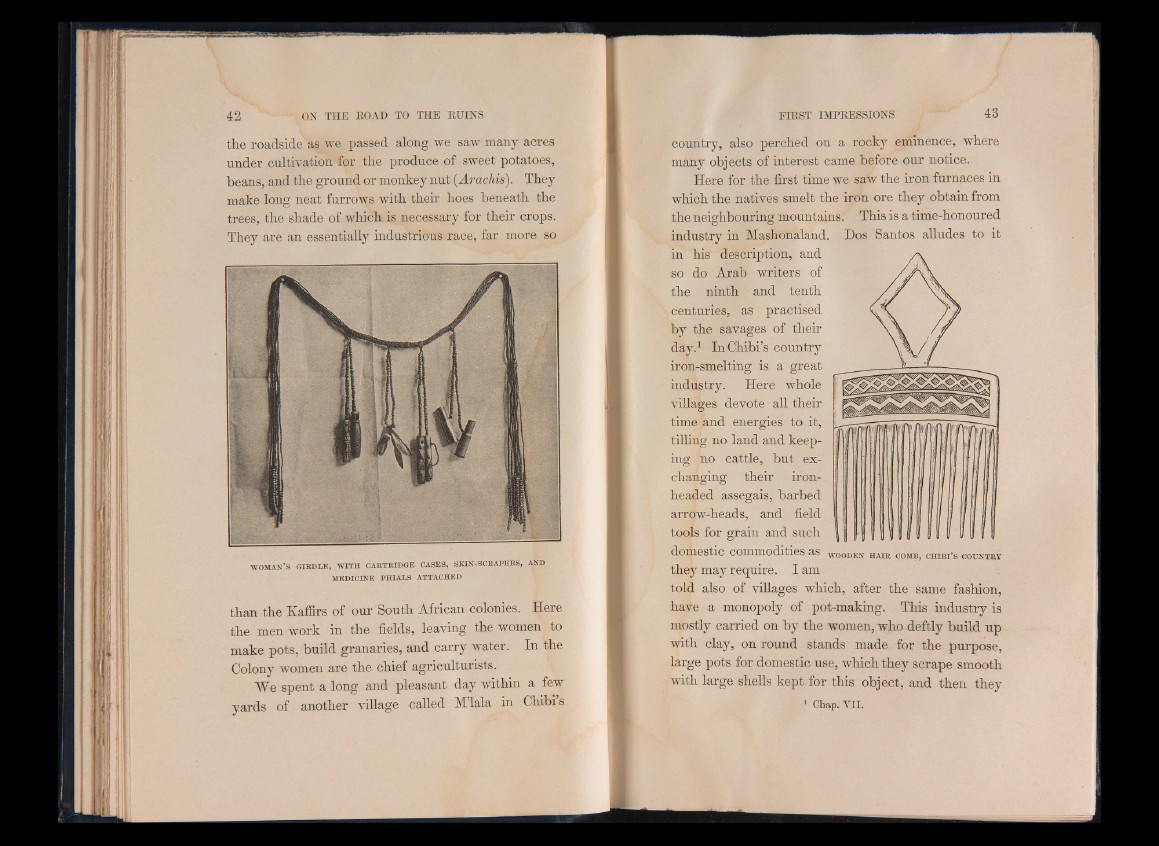

w o m a n ’s g ir d l e , w i t h c a r t r id g e c a s e s , s k in - s c r a p e r s , a n d

MEDICINE PHIALS ATTACHED

than the Kaffirs of our South African colonies. Here

the men work in the fields, leaving the women to

make pots, build granaries, and carry water. In the

Colony women are the chief agriculturists.

We spent a long and pleasant day within a few

yards of another village called M’lala in Chibi’s

country, also perched on a rocky eminence, where

many objects of interest came before our notice.

Here for the first time we saw the iron furnaces in

which the natives smelt the iron ore they obtain from

the neighbouring mountains. This is a time-honoured

industry in Mashonaland. Dos Santos alludes to it

in his description, and

so do Arab writers of

the ninth and tenth

centuries, as practised

by the savages of their

day.1 In Chibi’s country

iron-smelting is a great

industry. Here whole

villages devote all their

time and energies to it,

tilling no land and keeping

no cattle, but exchanging

their iron-

headed assegais, barbed

arrow-heads, and field

tools for grain and such

domestic commodities as w o o d e n h a i r c om b , c h i b i ’s c o u n t r y

they may require. I am

told also of villages which, after the same fashion,

have a monopoly of pot-making. This industry is

mostly carried on by the women, who deftly build up

with clay, on round stands made for the purpose,

large pots for domestic use, which they scrape smooth

with large shells kept for this object, and then they

1 Chap. VII.