of Zimbabwe and the present race, who built these

ruins ? or are we to imagine them to be the work of

the Makalangas themselves in the more flourishing

days of the Monomatapa rule P I am decidedly

myself of the latter opinion. No one who had carefully

studied the Great Zimbabwe ruins could for a

moment suppose them to be the work of the same

people; yet they are just the sort of buildings an uncivilised

race would produce, who took as their copy

the gigantic ruins they found in their midst. For the

next few weeks we were constantly coming across these

ruins, and the study of them interested us much.

Mount Masunsgwe was a conspicuous landmark

for us for several days about here. It is a massive

granite kopje, placed as a sort of spur to the range

of hills which surrounds ’Mtoko’s country. It is also

covered with similar ruined stone walls belonging to

a considerable town long since abandoned. The next

day we crossed a stream near a village, called the

Inyagurukwe, where the natives were busily engaged

in washing the alluvial soil in search of gold. We

halted for the night by another stream, under the

impression that Mangwendi’s was only about four

miles off, and that an easy day was in store for us.

But the fates willed otherwise. Shortly after passing a

large village, where the inhabitants were more than

usually importunate to see my wife’s hair, screaming

i Youdzi! voudzi! ’—Hair! h a ir!—as they scampered

by our side until she gratified their curiosity, we all

lost our way in an intricate maze of Kaffir paths. Our

interpreter was ahead and took one way; my wife and

I on horseback, in attempting to follow him, took

another; Mr. Swan on foot took another; and what

happened to the men with the donkeys we never knew,

for they did not reach Mangwendi’s till late m the after

noon, complaining bitterly of their wanderings. We

thought we were making straight for our goal, when

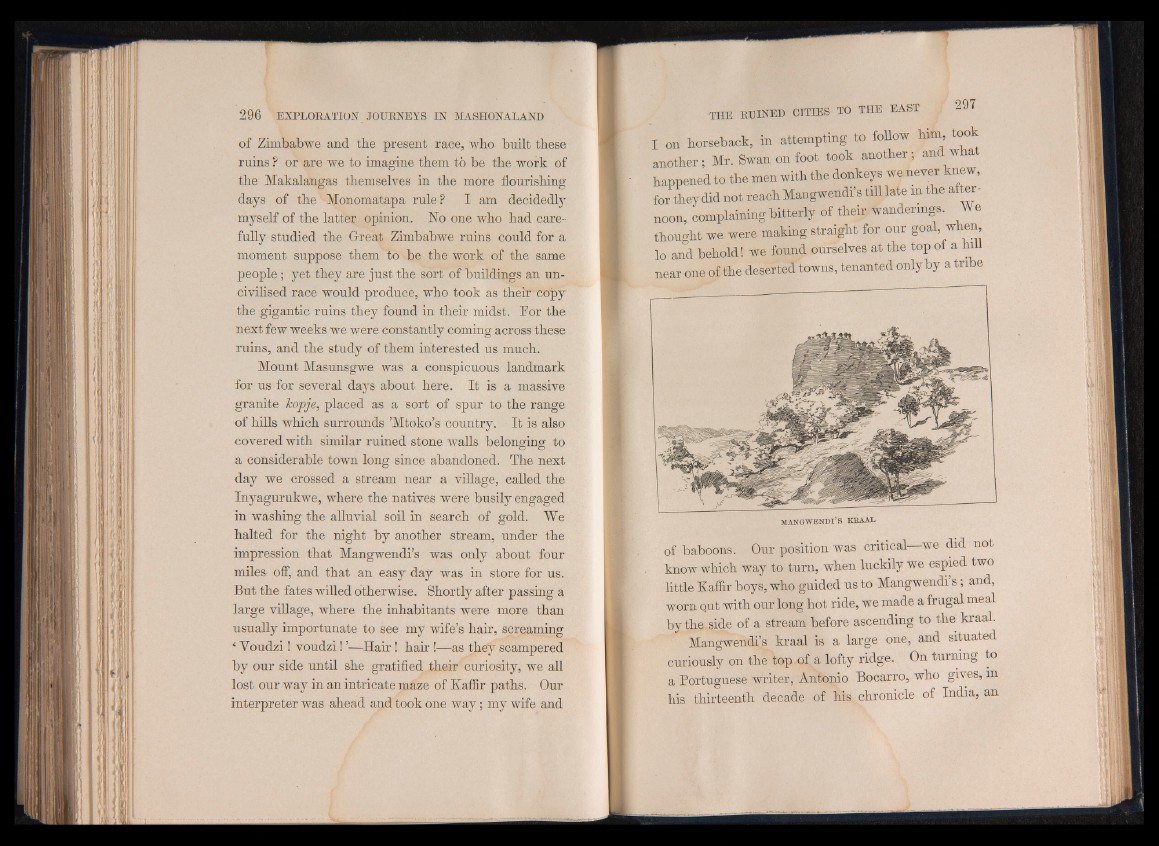

lo and behold! we found ourselves at the top of a hill

near one of the deserted towns, tenanted only by a tribe

M A N GW EN D l’S KRAAL

of baboons. Our position was critical—we did not

know which way to turn, when luckily we espied two

little Kaffir boys, who guided us to Mangwendi s ; and,

worn Qut with our long hot ride, we made a frugal meal

by the, side of a stream before ascending to the kraal.

Mangwendi’s kraal is a large one, and situated

curiously on the top of , a lofty ridge. On turning to

a Portuguese writer, Antonio Bocarro, who gives, in

his thirteenth decade of his chronicle of India, an