The following morning we watched with some

interest a trader from Fort Salisbury selling goods

to the natives. Beads, gunpowder, and salt were

the favourite commodities he had to offer, in return

for which he rapidly acquired a fine lot of pumpkins,

maize, potatoes, and other vegetables; whilst

for blankets and rifles he obtained cattle which I

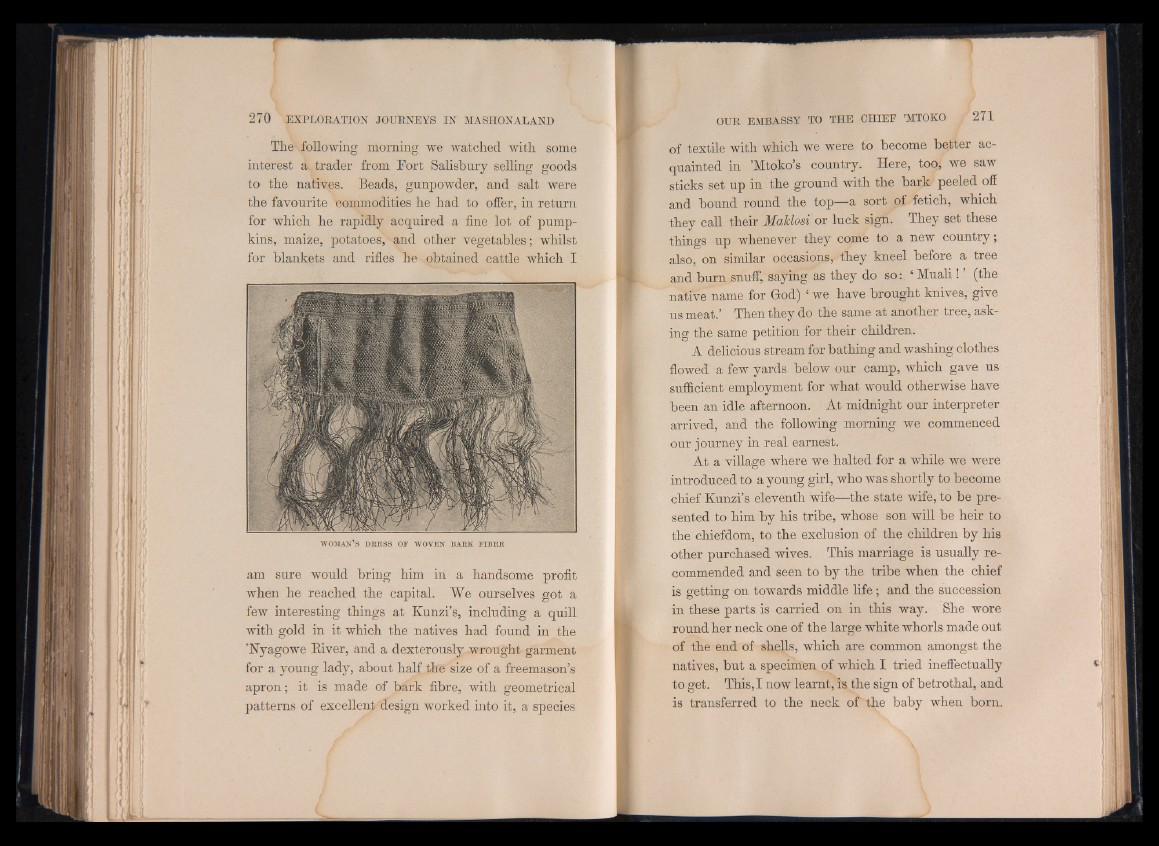

w o m a n ’s d r e s s o f w o v e n b a r k f i b r e

am sure would bring him in a handsome profit

when he reached the capital. We ourselves got a

few interesting things at Kunzi’s, including a quill

with gold in it which the natives had found in the

’Nyagowe Kiver, and a dexterously wrought garment

for a young lady, about half the size of a freemason’s

apron ; it is made of bark fibre, with geometrical

patterns of excellent design worked into it, a species

of textile with which we were to become better acquainted

in ’Mtoko’s country. Here, too, we saw

sticks set up in the ground with the bark peeled off

and bound round the top—a sort of fetich, which

they call their MaUosi or luck sign. They set these

things up whenever they come to a new country;

also, on similar occasions, they kneel before a tree

and burn snuff, saying as they do so: ‘ Muali! ’ (the

native name for God) ‘we have brought knives, give

us meat.’ Then they do the same at another tree, asking

the same petition for their children.

A delicious stream for bathing and washing clothes

flowed a few yards below our camp, which gave us

sufficient employment for what would otherwise have

been an idle afternoon. At midnight our interpreter

arrived, and the following morning we commenced

our journey in real earnest.

At a village where we halted for a while we were

introduced to a young girl, who was shortly to become

chief Kunzi’s eleventh wife—the state wife, to be presented

to him by his tribe, whose son will be heir to

the chiefdom, to the exclusion of the children by his

other purchased wives. This marriage is usually recommended

and seen to by the tribe when the chief

is getting on towards middle fife; and the succession

in these parts is carried on in this way. She wore

round her neck one of the large white whorls made out

of the end of shells, which are common amongst the

natives, but a specimen of which I tried ineffectually

to get. This, I now learnt, is the sign of betrothal, and

is transferred to the neck of the baby when born.