The conditions necessary to produce this power in its fullest

extent are,—large and strong pectoral muscles; great extent

of surface, as well as peculiarity of form, in the wing:

and feathers of firm texture, strong in the shaft, with the

filaments of the plume arranged and connected to resist

pressure from below. The extent of surface, the form and

other peculiarities of the wings, have been already noticed,

and the anatomical part only requires to be briefly described.

A certain degree of weight is necessary to flight*, and this

is imparted by large pectoral muscles; the power of these

muscles may he estimated by the depth of the keel, and the

breadth of the sides of the breast-bone or sternum; as

affording extent of surface for the attachment of those large

muscles by the action of which the wings are moved.

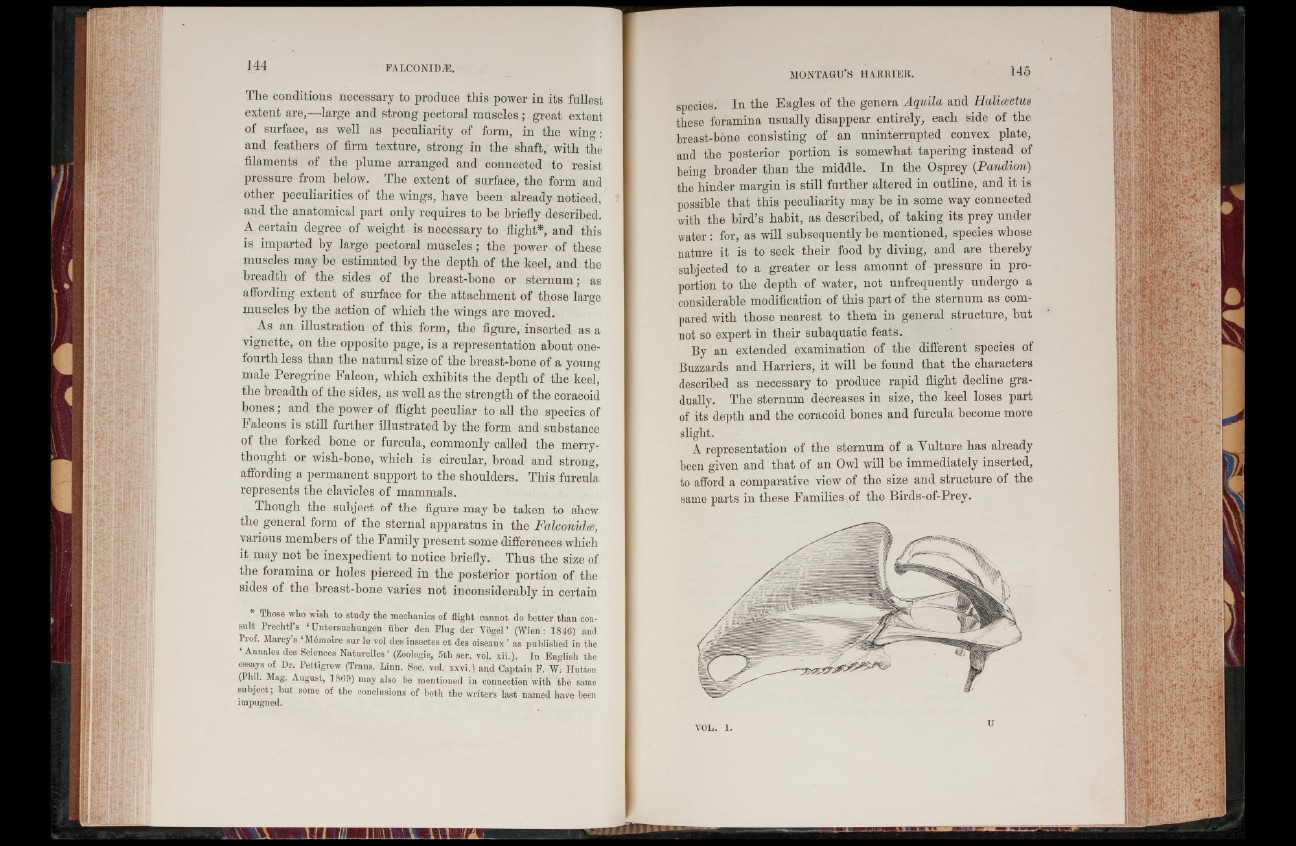

As an illustration of this form, the figure, inserted as a

vignette, on the opposite page, is a representation about one-

fouith less than the natural size of the breast-bone of a young

male Peregrine Falcon, which exhibits the depth of the keel,

the breadth of the sides, as well as the strength of the coracoid

bones; and the power of flight peculiar to all the species of

Falcons is still further illustrated by the form and substance

of the forked bone or furcula, commonly called the merrythought

or wish-bone, which is circular, broad and strong,

affording a permanent support to the shoulders. This furcula

represents the clavicles of mammals.

Though the subject of the figure may be taken to shew

the general form of the sternal apparatus in the Falconidce,

various members of the Family present some differences which

it may not be inexpedient to notice briefly. Thus the size of

the foramina or holes pierced in the posterior portion of the

sides of the breast-bone varies not inconsiderably in certain

* Those who wish to study the mechanics of flight cannot do better than consult

Prechtl’s 1 Untersuchungen über den Flug der Vogel’ (Wien: 1846) and

Prof. Marey’s ‘Mémoire sur le vol desinsectes et des oiseaux’ as published in the

‘ Aúnales des Sciences Naturelles’ (Zoologie, 5th ser. vol. xii.). In English the

essays of Dr. Pettigrew (Trans. Linn. Soe. vol. xxvi.) and Captain F. W. Hutton

(Phil. Mag. August, 1869) may also be mentioned in connection with the same

subject; but some of the conclusions of both the writers last named have been

impugned.

species. In the Eagles of the genera Aquila and Haliceetus

these foramina usually disappear entirely, each side of the

breast-bone consisting of an uninterrupted convex plate,

and the posterior portion is somewhat tapering instead of

being broader than the middle. In the Osprey (Pandion)

the hinder margin is still further altered in outline, and it is

possible that this peculiarity may he in some way connected

with the bird’s habit, as described, of taking its prey under

water: for, as will subsequently be mentioned, species whose

nature it is to seek their food by diving, and are thereby

subjected to a greater or less amount of pressure in proportion

to the depth of water, not unfrequently undergo a

considerable modification of this part of the sternum as compared

with those nearest to them in general structure, but

not so expert in their subaquatic feats.

By an extended examination of the different species of

Buzzards and Harriers, it will be found that the characters

described as necessary to produce rapid flight decline gradually.

The sternum decreases in size, the keel loses part

of its depth and the coracoid bones and furcula become more

slight.

A representation of the sternum of a Vulture has already

been given and that of an Owl will be immediately inserted,

to afford a comparative view of the size and structure of the

same parts in these Families of the Birds-of-Prey.